Gov. Kathy Hochul officially revived congestion pricing at a Thursday announcement. The Manhattan tolls, which will take effect at the start of 2025, were slashed by 40% from the rates that were originally approved under the paused June plan.

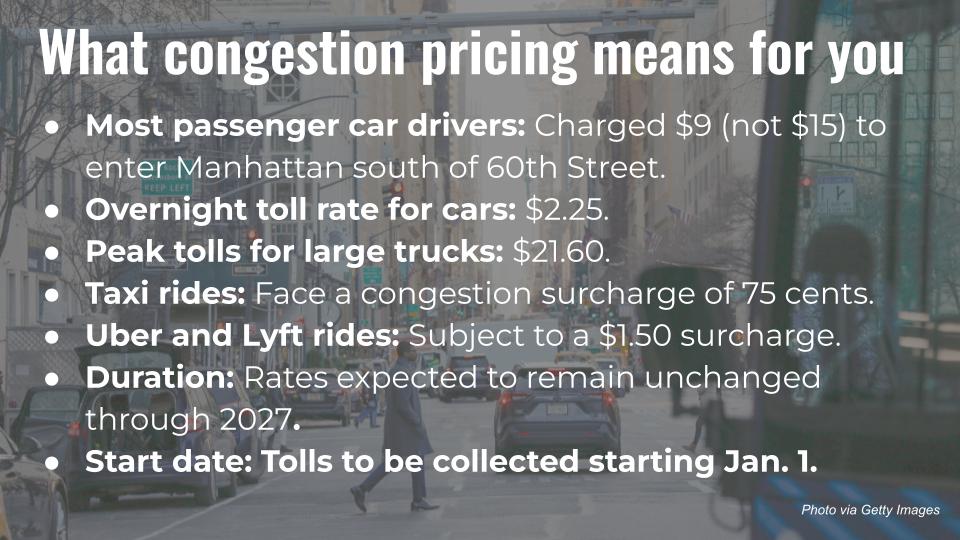

The toll for most motorists entering Manhattan south of 60th Street will be reduced from $15 to $9. Rates are also set to be reduced across the board by 40%, including for small and large trucks, discounts for overnight trips into the central business district, and per-ride surcharges on taxi, Uber, and Lyft rides.

The tolls, originally set to go into effect on June 30 before Hochul paused it weeks before the start date, will now start being collected in January 2025.

The governor said the reduced tolls are still expected to be enough collateral to raise $15 billion from the bond market to pay for capital improvements to the MTA system, including extending the Second Avenue Subway, replacing ancient subway signals that frequently break, rolling out a new generation of railcars, and improving accessibility in the subway system with elevators and ramps.

“I believe no New Yorker should have to pay a penny more than is necessary to achieve these goals, and $15 was just too much,” said Hochul. “We have found a path to fund the MTA, reduce congestion, and keep millions of dollars in the pockets of our commuters.”

What’s more, the governor also directed the MTA to improve bus service frequency on 23 routes in the outer boroughs, which was not part of the original plan.

Large trucks’ peak toll rates will fall from $36 down to $21.60, while cars will pay an overnight toll rate of $2.25 instead of $3.75. Taxi rides will see a congestion surcharge of 75 cents instead of $1.25, while Uber and Lyft surcharges will drop from $2.50 to $1.50.

Under Hochul’s plan, the toll is not expected to be raised above $9 before 2027, nor above $12 before 2030.

Bumps in the road

The move is the second dramatic about-face for Hochul on congestion pricing in less than a year. Hochul was initially a strong supporter of congestion pricing until her abrupt decision to “pause” the toll in June, with just over three weeks before it was set to turn on. She justified the move — which drew two separate lawsuits from congestion pricing supporters — as a reaction to high levels of inflation and issues around affordability for New Yorkers.

The federal government conducted a long environmental review on congestion pricing, ultimately recommending a base toll between $9 and $23. An internal MTA tribunal called the Traffic Mobility Review Board then recommended $15, a level that was approved by the MTA Board.

By pursuing the $9 toll, Hochul assumes that the new toll will not require another environmental assessment, just a “re-evaluation” by the feds that her administration expects to be completed “expeditiously,” followed by a 30-day public review period required by law. The new toll structure will go to a vote before the MTA Board next week.

If approved, as expected, the feds, state, and city can then sign a document authorizing a “Value Pricing Pilot Program,” or VPPP, which Hochul had previously ordered her Transportation Commissioner to withhold her signature from, the legal mechanism by which she was able to enact the pause and which was at issue in the lawsuits from advocates.

All told, Hochul expects the toll to be ready to go by Jan. 5.

Trump doesn’t like it

That timeline is crucial because of the new administration set to take power in Washington. On the campaign trail, Donald Trump promised to “TERMINATE” congestion pricing in his first week in office, and New York Republicans already have it in their crosshairs. In a statement, Trump said despite his “great respect” for Hochul, he “strongly disagree[s] with the decision on the congestion tax,” which he calls “the most regressive tax known to womankind(man!).”

“It will put New York City at a disadvantage over competing cities and states, and businesses will flee,” said Trump. “It will be virtually impossible for New York City to come back as long as the congestion tax is in effect.”

Notably, however, the president-elect did not say anything about plans to “terminate” it once in office.

In response, MTA chief Janno Lieber noted that most of the workers at Trump’s Manhattan office likely take mass transit into work and contended they, and his business empire, would benefit from transit investments. About 85% of commuters into Manhattan’s central business district take mass transit, while just 11% drive.

“He’s a New Yorker,” said Lieber. “I think that there’s a real possibility, if he takes a hard look at the issue, as a New Yorker, he will understand.”

Balancing the MTA needs

Questions remain, however, about the new tolling structure. A 40% reduction in tolls means 40% less revenue, but Albany contends the reduced revenue will still satisfy the bond market to underwrite $15 billion in debt. Hochul’s budget director, Brian Washington, said the bonds would likely be issued over a longer period of time, and consequently capital projects would be paid for and undertaken over a longer timeline; the Second Avenue Subway and ADA accessibility would be higher on the priority list, he noted.

“We’re required to give the MTA basically a $15 billion credit card,” said Kathryn Garcia, Hochul’s director of state operations. “We’ve given them the $15 billion credit card, and figuring out the back end on paying off your debt, they haven’t spent any of their 15 billion yet, they’re going to almost immediately, and then they’ll start paying that off. And they will have the cash flow as we move forward to do that, it just may mean that it takes longer to pay it all back.”

The lower toll would likely only bring in about $600 million per year to the MTA, rather than the $900 million-$1 billion previously forecasted, meaning projects would go forward at a slower pace even as the MTA’s transportation assets, like signals, railcars, and elevated structures, age into decrepitude.

The MTA’s investments in its 2020-24 capital plan had already been on “pause” before congestion pricing was “paused,” due to numerous lawsuits by opponents attempting to overturn the program. Most were dismissed in the Southern District of New York, though a federal lawsuit filed by New Jersey is still active.

Resistance across the river

In a statement, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy assured the public that Hochul’s move to reduce the tolls had not appeased his vociferous opposition, and he still intended to fight against the plan in court.

“I am firmly opposed to any attempt to force through a congestion pricing proposal in the final months of the Biden Administration,” said Murphy. “All of us need to listen to the message that voters across America sent last Tuesday, which is that the vast majority of Americans are experiencing severe economic strains and still feeling the effects of inflation.”

While Hochul stood firm that her reasons for pausing congestion pricing were economic, not political, she faced persistent rumors that the real reason was to help Democrats in suburban swing House districts, where the toll was especially unpopular and Republicans made significant gains in the last election cycle. Democrats did win back three House seats in New York, though they were not enough to secure a Democratic majority in Washington’s lower chamber; it’s unclear what, if anything, congestion pricing had to do with those victories.

Upon reviving the toll, the governor once again said politics had nothing to do with it — despite the five-month pause ending just a week after the national election, which was won by an opponent of the scheme.

“I think if people had just, you know, taken me at my word back in June when I said this is a pause and we’ll get to a solution by the end of the year, we could have solved a lot of problems,” said Hochul. “If you take the election out of it, this is a very normal sequence of events.”