BY TIMOTHY GARDNER, Reuters

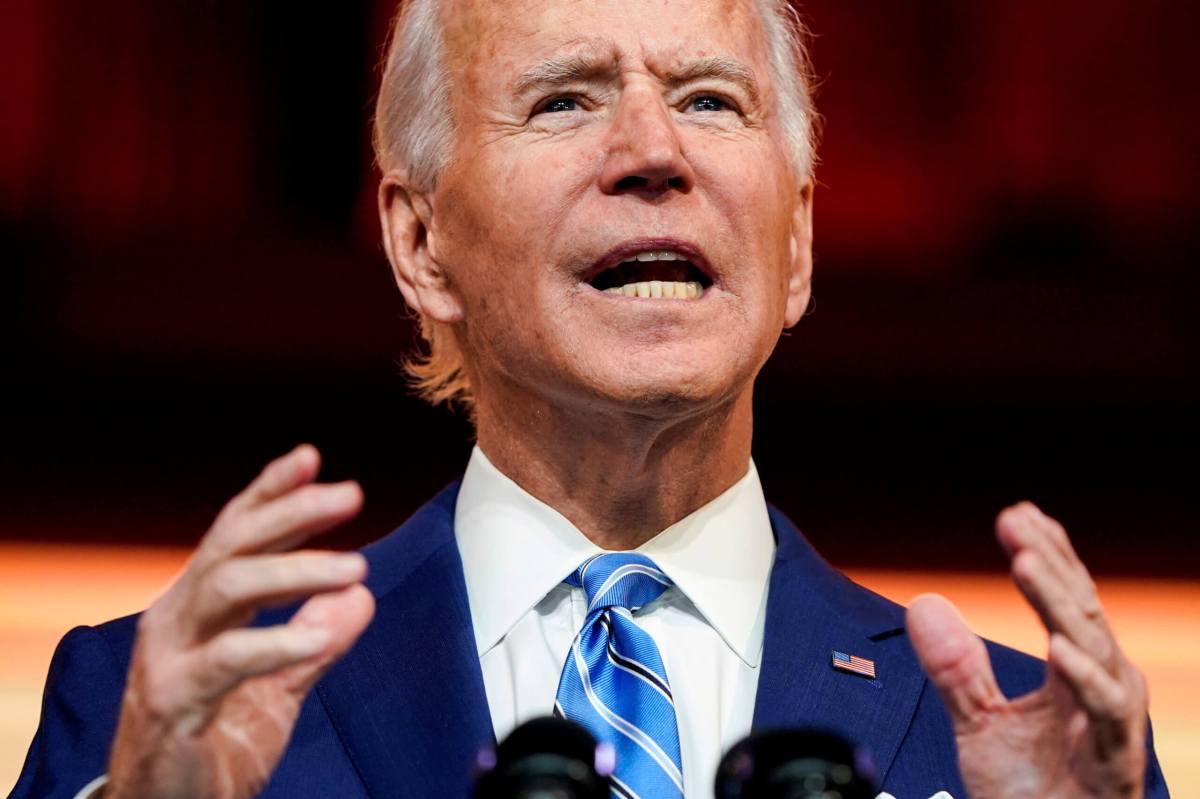

President-elect Joe Biden’s promise to end U.S. fossil fuel subsidies worth billions of dollars a year for drillers and miners could be hard to keep due to resistance from lawmakers in a narrowly divided Congress, including from within his own party.

The challenge reflects just one of the obstacles that Biden will need to overcome as he seeks to usher in sweeping measures to combat climate change and transform the nation’s economy to net-zero emissions within three decades. Biden has said axing fossil fuel subsidies will generate money to help pay for his broader $2 trillion climate plan.

While Biden can take executive action to reverse outgoing President Donald Trump’s rollbacks of rules meant to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, reforming tax breaks that allow companies to produce oil, gas and coal more cheaply will require Congress to pass legislation.

Doing so could be hard, even though Biden spent 36 years in the Senate, where he is known as a dealmaker.

“It’s dead on arrival in the Senate,” said Gilbert Metcalf, a former deputy assistant secretary for environment and energy at the Treasury Department under former President Barack Obama, referring to any standalone legislation ditching the tax breaks if Republicans maintain control of the chamber.

Even if two of Biden’s fellow Democrats win runoff votes in Georgia on Jan. 5, bringing the Senate to a 50-50 split with Vice President-elect Kamala Harris acting as tie breaker, chances of passing a tax package are slim, experts said.

That is because moderate Democrats from fossil fuel producing states, like Senators Martin Heinrich of New Mexico and Joe Manchin of West Virginia, the top Democrat on the Senate Energy Committee, could stymie the effort.

“In states like New Mexico, where senators might be green enough to support a climate bill … a measure that merely strips tax provisions looks like a non-starter,” said Kevin Book, an analyst at ClearView Energy Partners.

Neither Manchin’s office, nor Heinrich’s responded to requests for comment.

Obama also wanted to ditch tax breaks for fossil fuels to send a signal to the world that the United States was serious about speeding a transition away from fossil fuels to tackle climate change.

But even with a commanding Democratic majority in the Senate in Obama’s first six years in office, he was unable to kill the subsidies.

The Biden transition team did not respond to a request for comment.

A global signal?

Doing away with tax breaks on producers of fuels that emit greenhouse gases would fit neatly with Biden’s pro-climate agenda, which marks a reversal from Trump’s efforts to roll back climate regulations while boosting fossil fuel output.

It would help establish the United States as a global leader on climate, potentially helping convince other big emitters to axe fossil fuel subsidies.

Leaders in the G20 resolved in 2009 to ditch the subsidies but have made little progress.

“It’s harder for us to get a country to do something if we’re not doing it ourselves,” said Metcalf.

Estimates of the value of fossil fuel subsidies, which mainly take the form of tax breaks, vary.

Bob McNally, the president of the consultancy Rapidan Energy Group, estimates they run $15 billion a year. The nonprofit Environmental and Energy Study Institute puts them at $20 billion annually.

Estimates that consider the health care costs linked to pollution from fossil fuels put the subsidies even higher.

One U.S. tax break, called intangible drilling costs, allows producers to deduct a majority of their costs from drilling new wells. The Joint Committee on Taxation, a nonpartisan panel of Congress, has estimated that ditching it could generate $13 billion for the public coffers over 10 years.

Another, the percentage depletion tax break which allows independent producers to recover development costs of declining oil gas and coal reserves, could generate about $12.9 billion in revenue over 10 years, according to the panel.

Biden and Congress will be under pressure to reduce the federal deficit by cutting such tax breaks. But wider tax reforms will also take up debate such as corporate tax rates and boosting taxes on the biggest earners, some of which might take priority.

Any bill to alter the tax provisions for the fossil fuel sector will also face heavy resistance from lobbyists, some of whom may point out that solar, wind and other non-fossil energy sources also receive substantial taxpayer support.

The American Petroleum Institute, the country’s biggest oil and gas lobby group, will “advocate for a tax code that supports a level playing field for all companies regardless of economic sector,” said Frank Macchiarola, a senior vice president at the industry group.

API will push for “pro-development policies that sustain and grow the billions of dollars in government revenue our industry generates at the state and federal level,” he said.