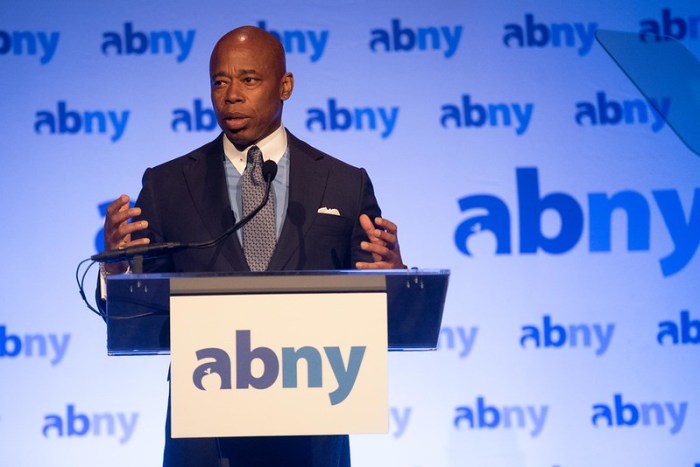

Mayor Eric Adams and Governor Kathy Hochul unveiled a massive 150-page report Wednesday containing 40 proposals aimed at transforming the city’s economy for the post-COVID-19 era at the Association for a Better New York (ABNY) Power Breakfast.

Dubbed “New’ New York: Making New York Work for Everyone,” the report was developed over the past six months by a panel of the same name launched by Adams and Hochul in May. It’s co-chaired by Robin Hood CEO Richard Buery and chief executive of Sidewalk Labs Daniel Doctoroff – both former deputy mayors in previous mayoral administrations.

The plan was built around three central tenets: “reimagining” the role of Midtown and the city’s other business districts, shortening commute times and growing the Big Apple’s economy with a focus on equity.

“We have to ensure that people know that these are business districts but they are not limited to that,” Hochul said while describing the plan’s central pillars.

“They don’t have to just be for business any longer,” she continued. “Why can’t we have people living there as well? That’s the radical idea we’re talking about here today. We gotta also make it easier for people to get to work. Improving commutes to Manhattan, we’re gonna keep focusing on that. Strengthening our employment hubs and workplaces to be closer to home. We’re gonna be continuing to create jobs.”

The governor said the panel’s charge was to craft a plan that was a true collaboration between the state and the city, which is something that seemed almost unimaginable under her and Adams’ predecessors – Andrew Cuomo and Bill de Blasio – who were locked in a public feud for much of their overlapping tenures.

“Over the past five months, [the panel] worked around the clock, [they] worked so hard,” Hochul said. They had “one goal: a coordinated joint policy agenda and action plan, and here’s the radical part, between the city and the state. See how crazy that is? Working together. Because, guess what? I represent the same people, the same places and the same businesses that the mayor does.”

Part of the panel’s charge, Adams said, was to consider what work will look like in the post-pandemic period and how those changes could impact the city’s economy overall.

“We’re going to lean into the difficult conversation about what work should look like,” he said. “That’s what this New New York panel was about. Yes, we’re going to have a combination of remote work, but we’re gonna have to have a real conversation about how that impacts those mom and pop stores that depend on foot traffic.”

The first goal of the report is reshaping the role of Midtown Manhattan, and the city’s other business hubs, by turning them into round-the-clock communities where people can still work, but also live and spend their free time.

“People don’t necessarily have to come back to those neighborhoods,” Buery said. “But if people don’t have to come back to those neighborhoods, then our job is to say ‘how can we make them neighborhoods that people want to come back to?’”

There are several key steps to realizing that vision, Doctoroff said: making it easier to convert commercial office buildings into spaces that can serve other purposes, like housing, and improving the quality of life in business districts in terms of sustainability, sanitation and road safety.

In Midtown, he said, this means dramatically expanding the amount of public space in the area, a plan for which is laid out in the report.

When it comes to making it easier for people to get to their jobs, Doctoroff said, there has to be better public transit service across the five boroughs – a problem that has plagued the city for many years. That could mean yanking some private cars off the road, he said, which could be achieved through the congressional pricing plan to toll cars in Manhattan below 60th Street, which could launch in the city by the end of next year.

Another way, Doctoroff said, is by making it easier for people to work by where they live, something that’s been made easier by the movement of jobs from Manhattan to the outer boroughs over the past couple of decades.

“We can certainly make it more appealing to come to Midtown and lower Manhattan,” he said. “But we also have to accept the fact that people are going to work where they’re going to work and what we need to do is make this place the best place to work, period.”