The city’s Open Streets program brought significant economic advantages to bars and restaurants along their corridors, even as the COVID-19 pandemic that instigated it brought pain to small businesses across the city, according to a new report from the city’s Department of Transportation.

The study, conducted in tandem with Bloomberg Philanthropies, found that businesses along Open Streets recovered more quickly than their counterparts on nearby commercial roads retaining automobile traffic. Through the first 18 months of the pandemic, restaurants and bars on Open Streets saw their sales grow by an average of 19% above pre-pandemic baseline levels, while those on “control corridors” saw a 29% decline in sales.

Open Streets also enabled more bars and restaurants to stay afloat amidst the economic calamity of the pandemic and enabled faster growth of new business openings along their stretches, according to the report.

“The report proves what we all have seen for two years,” said DOT Commissioner Ydanis Rodriguez at a Tuesday press conference along Chinatown’s Doyers Open Street, one of the areas studied. “New Yorkers not only love dining outdoors. When given the choice, they prefer to spend their time and money along car-free Open Streets.”

Open Streets originated in May 2020 amidst the COVID-19 lockdown in the city, with the de Blasio administration shutting short segments of roadway to automobile traffic to give holed-up residents space to walk around outside. When pandemic restrictions started being lifted the following month, the city significantly eased existing restrictions on eateries setting up outdoor dining, enabling thousands of restaurants to take over street and sidewalk space and construct sheds for al-fresco feasting to prevent the spread of COVID indoors.

Open Streets and outdoor dining, officially deemed Open Restaurants, were a natural fit for each other, and car-free roadways have since become havens for European-style street cafés as well as space to hang out. Open Restaurants has been credited with saving 100,000 jobs by the city and the New York City Hospitality Alliance, a major trade group in the industry.

Now, advocates and the Adams administration are touting hard data they say proves the industry is buoyed not just by outdoor dining, but by being on walkable streets free from the automobile.

“Cars don’t shop or dine out. People do,” Rodriguez said. “We now have hard evidence.”

To conduct the study, DOT examined sales tax data reported to the Department of Finance from March 2020 to August 2021 by restaurants along five Open Streets: Ditmars Boulevard in Astoria, Pell and Doyers streets in Chinatown, East 32nd Street in Koreatown, 5th Avenue in Park Slope, and Vanderbilt Avenue in Prospect Heights, along with comparable nearby corridors without an Open Street, and measured those numbers against a baseline average from 2017 through early 2020.

The results were stark: in four out of five cases, sales on Open Streets shot up to the stratosphere as control corridors saw steep declines. While sales on Doyers Street were down, the tapering was significantly less than nearby on the Bowery.

The Open Streets studied also saw considerably higher numbers of businesses surviving the pandemic than control groups, and a higher proportion of new business openings.

“The recipe of outdoor dining, Open Restaurants, and Open Streets is a recipe for economic development, economic activity, social activity that brings the streets back to the people,” said Andrew Rigie of the NYC Hospitality Alliance. “And we’re so thrilled we now have data to tell that story, to inform the policymaking.”

Not everyone has been a fan of Open Streets and Open Restaurants, of course. Outdoor dining has been the subject of several lawsuits seeking to toss the program, with incensed locals concerned by the loss of parking spaces and sidewalk sheds they say have attracted rats and other unsavory elements.

Opponents of Open Restaurants are counting on members of the City Council — such as Speaker Adrienne Adams, a critic of street sheds — to pare down the program as they seek to make it permanent, such as by transferring jurisdiction from DOT back to the smaller Department of Consumer and Worker Protection, or by placing new regulations to curb restaurants’ ability to use roadways for dining structures.

Shannon Phipps, president of the Berry Street Alliance — a neighborhood group vociferously opposed to the Open Street on the namesake Brooklyn thoroughfare — called the DOT study “flimsy” and argued that all it proved was that Open Streets are good for bar owners reaping in profits.

“The only people who really love it are bars and restaurants that got subsidized by the government and got free space,” Phipps told amNewYork Metro. “So, shocker that they did well.”

Phipps says that for Williamsburg residents like herself, the Open Street has only brought previously-unheard-of levels of noise, causing sleep deprivation for locals as out-of-towners descend on her street to party and drink.

“We’ve been here for decades, and many of us are newcomers. And we just want to have a residential, interior life that is quiet and safe,” Phipps said. “While people enjoy coming to other people’s neighborhoods and partying and entertaining themselves, I would say just remember to be neighborly, people actually live there and everyone’s on a different schedule.”

But others see the program as bringing only vitality.

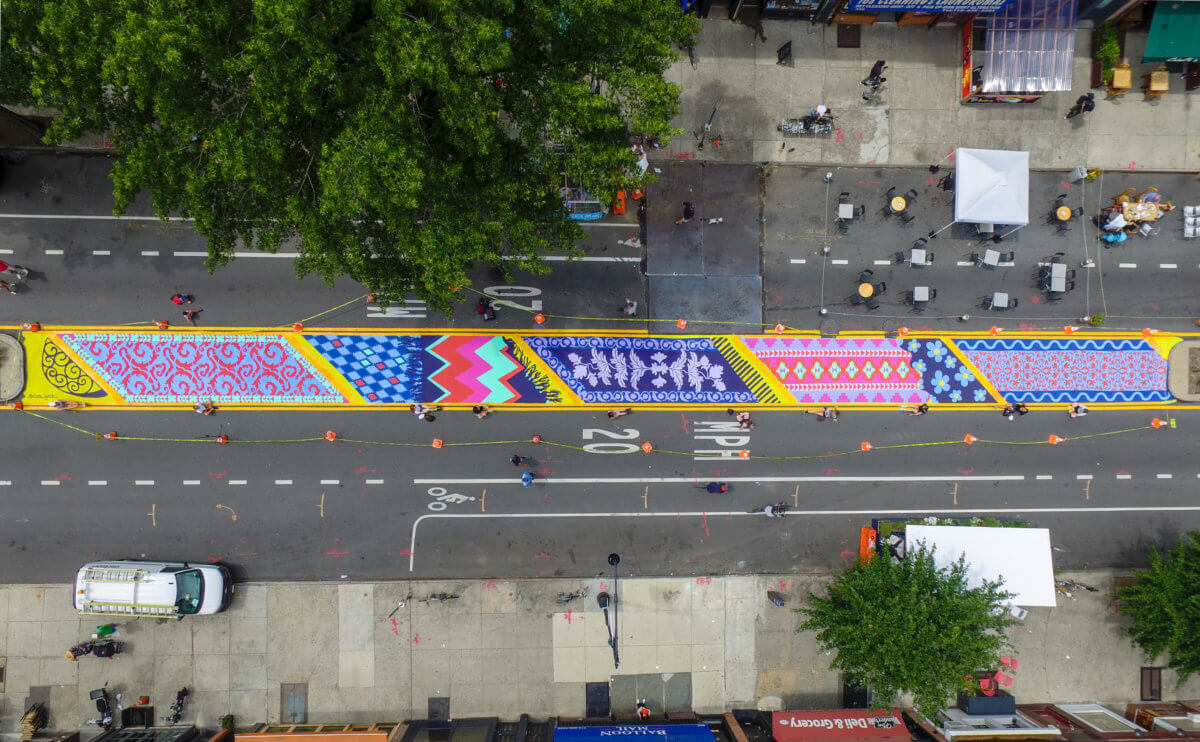

Wellington Chen, executive director of the Chinatown Business Improvement District, says that the Doyers Open Street — which saw the old alleyway painted in vibrant colors as local restaurants like historic Nom Wah Tea Parlor set up streeteries — has made the area feel more like a community as notoriously brusque New Yorkers stop to say hi to one another.

“It becomes a very social place,” Chen said. “This turned into a mini-Paris.”

So popular has been the Doyers Open Street that one local business owner interrupted Rodriguez at the press conference, begging DOT to close off nearby Mott Street to cars in the hope of attracting an influx of customers. The commissioner said he would work with the business owner as the city continues to prioritize expanding Open Streets.

“The future of New York City is going car-free,” Rodriguez said. “And the future under Mayor Eric Adams is to reimagine the use of public space.”