This is the second part in amNewYork Metro’s series “Still Racing to Deliver,” a follow-up to our five-part series exploring the proliferation of quick-commerce grocery services in New York City. In “Still Racing to Deliver,” we catch up with the industry, which has changed rapidly in the last ten months, and how it has impacted the city, local businesses, and more. Click here to read parts one, three, and four.

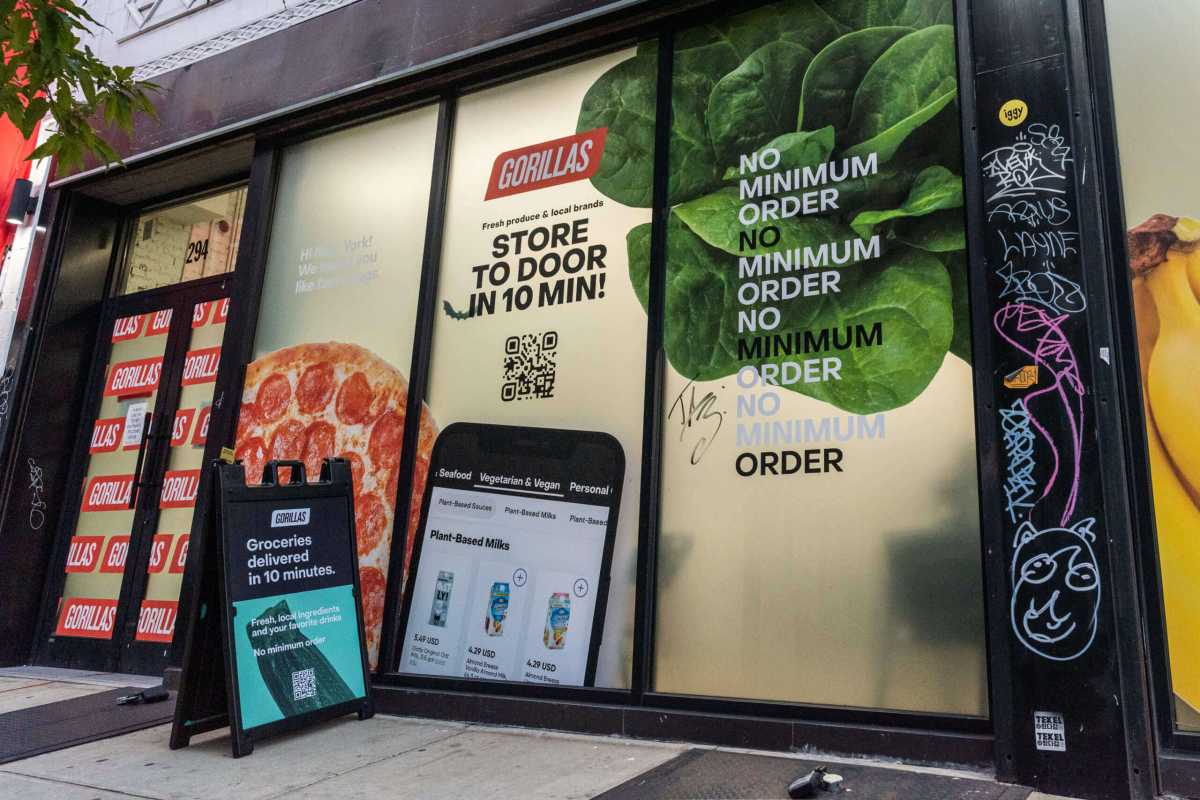

Last year, as quick-commerce grocery delivery services swept through the city, buying up retail and advertising space and wooing customers with a broad selection of groceries and other goods that could be delivered for a nominal fee within fifteen minutes, some of New York City’s best-known businesses were concerned.

The investor-backed companies weren’t necessarily trying to get New Yorkers to purchase their entire grocery list through their app — rather, they wanted to attract the customer who forgot one or two ingredients for dinner, or paper towels.

As a result, the city’s grocery stores weren’t the ones most concerned about the threat the new companies might pose to their business models — it was the ubiquitous corner stores and bodegas, many of which were already struggling as the pandemic stretched on.

“The American Way is done,” Muhammad Esa, the owner of Farm Shop Deli on Fifth Avenue in Park Slope, told amNY at the time. “It’s just a thing of the past.”

Esa said he had owned the shop for 20 years, and learned the bodega business from his father and uncles, but changing markets had threatened the business models and profitability of convenience stores. At that time, the impact of apps like Gorillas and Getir still wasn’t clear, and Esa wasn’t the only person worried about what they would mean for bodegas.

But, less than a year later, the quick-commerce delivery bubble seems to have popped — or at least deflated. Just as fast as the new companies grew their footprints in the city, they’ve folded — JOKR, Fridge No More, 1520, and Buyk are all gone, leaving just a few competitors left.

The real impacts of quick-commerce grocery delivery apps

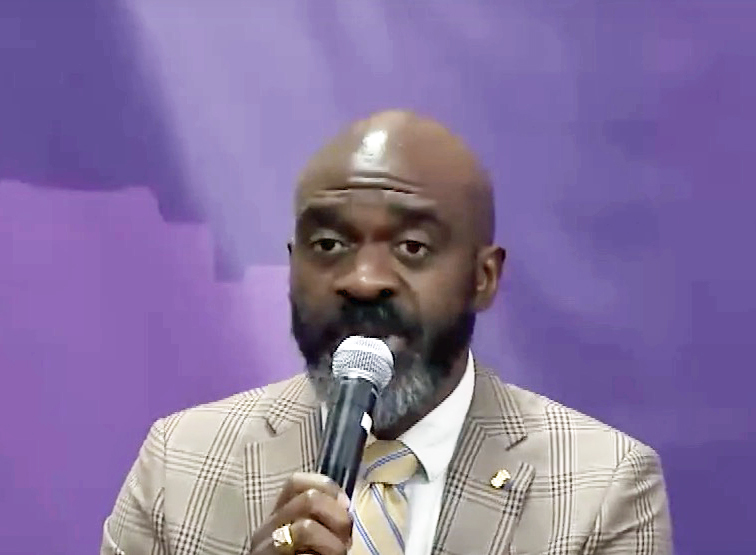

The bodegas are still here — and many never felt the effects of the delivery apps. The fear of what may have come ended up being greater than the actual impact, said Youssef Mubarez, director of public relations at the Yemeni-American Merchants Association, which works directly with dozens of bodega and other small business owners in Brooklyn.

“I’m in touch with the community, any big issue that’s coming around, I hear it,” Mubarez said. “I didn’t hear anything about ‘This quick-convenience store is affecting my business, it’s killing my business.’”

That doesn’t mean no one was worried about it, he said, just that the actual impacts were negligible. In part, he said, that’s because the city’s convenience stores are such an integrated part of their communities — large companies wading into the market for the first time couldn’t make those connections.

“When you compete with something that’s so in tune with the community, you’re missing a whole lot,” Mubarez said. “You can’t just throw up a shop, throw up tinted windows, and think you’re going to sell to a community that’s had a deli there that has an owner that everyone’s known for months, for years, and think you’re going to undercut them.”

He was referring to the “dark stores” the delivery companies operate out of. Also known as micro-warehouses, the stores are the cornerstone of quick delivery — rather than running their businesses out of one large warehouse, they utilize a large network of well-stocked dark stores.

Dark stores are usually closed to the public, with large advertisements plastered over the windows so would-be shoppers can’t see in, though Getir and Gopuff, two of the surviving delivery services, do allow pickup orders or in-person shopping.

One independent company, My Bodega Online, tried to meet the small businesses where they were. The app worked with a handful of bodegas and delis, mostly in the Bronx, connecting them with customers who wanted to order online.

My Bodega Online closed in June after years of stop-and-start, according to a social media post by founder Jose Bello.

“The problem has not been solved: mom-and-pop grocery stores need a new business model with technology to thrive,” Bello write. “We hoped that our ordering app with in-house delivery would be an answer. But timing and resources did not validate our thesis. And now we stop. Perhaps others will find a way, but after years of trying, we do not see our path forward.”

Wellington Z. Chen, executive director of Manhattan’s Chinatown Business Improvement District (BID), agreed. A few dark stores popped up in the district — including a Gorillas warehouse on Grand Street — but there wasn’t a “huge influx” as some had feared.

“The quick answer is no, we have not seen a huge influx of these stores, but then again, they are the dark stores, so you cannot see them,” he said. “But I do patrols every day, I just finished one this morning. We haven’t seen that many.”

He speculated the companies had largely stayed out of Chinatown in part because the area is relatively low-income and residents were less likely to be ordering potentially-pricey goods from the apps — while most marketed their low or nonexistent delivery fees, most of them carried plenty of high-end goods and no discounted store brands.

“Also, Chinese delivery and Chinatown delivery is known for its efficiency,” Chen added. “We have our own system, and we are faster in many cases than even the so-called quick-quick delivery.”

A December 2021 survey of dark stores conducted by now-councilmember Gale Brewer and civic organization BetaNYC found 118 dark stores citywide and four in and around Chinatown. In addition to the Grand Street Gorillas location, which is still open, the survey found three dark stores operated by three different companies just blocks outside of Chinatown — two on Rivington Street and one on Delancey Street. At least two of the three locations have shut down, as the companies that operated them — Buyk and JOKR — have closed.

Most of the discussion of the potential impact of new delivery services on local business was in the press, Chen said, especially in the English-language newspapers. In local Chinese publications, the companies got very little coverage.

“It’s not a major headline, unlike Asian hate crimes and attacks,” he said. “This type of issue is a less dominant topic, I would say it’s not even very seriously looked at.”

Bigger concerns for small businesses

While the legion of new delivery apps didn’t make much of a dent in business for bodegas and convenience stores, not everything is rosy. Inflation has pushed the cost of many goods up “tremendously,” Mubarez said, as rent costs continue to grow. Most businesses took a hit during the pandemic — especially stores in downtown areas that relied on office traffic for revenue, he said.

“But, you know, a lot of the ones who are able to operate effectively, like, move on with new technologies, have been able to maintain their business and some of them have done better,” he said. “There was a strong push for advancing our businesses toward technology. That meant not using an old credit card machine to manage all your transactions and managing inventory in a notebook, but getting an actual point-of-sale system.”

It also means working with existing delivery services like DoorDash, which partners with YAMA, and GrubHub, Mubarez said. Many business owners he works with say that 30-40% of their business comes through delivery as customers order convenience items and sandwiches.

A nice photo of one of the deli’s sandwiches on an app like DoorDash is a huge draw, Mubarez said. Even if they’re not competing against the VC-backed apps, bodegas have to adapt. Some have been slow to come around, he said, but the bodega business is usually also a family business — and as the younger sons and grandsons of owners take over, they’re ready to push forward.

The consequences of failing to move forward became apparent during the pandemic, he said. To apply for Paycheck Protection Program or Economic Injury Disaster loans, owners had to submit some basic paperwork, like payroll documentation. A lot of the YAMA community missed out, he said, because they didn’t have those things automated — they just keep records on paper.

“They’ve already felt the hit at that point,” he said. “We kind of stressed, look at the things around you: social media, Google reviews, point of sale systems, this is what everyone looks at these days. No one’s asking their neighbor, ‘Do you know where I can get a good sandwich,’ they’re going right online.”

The pandemic also brought business to a crawl in Chinatown — and the affects of the virus itself and the rise in hate crimes that accompanied it are still ringing in the neighborhood. A recent vacancy survey conducted by the BID and the city’s department of Small Business services found that 379 of the area’s 1,652 storefronts are vacant. But Chen said he feels things are going to improve soon.

Vacancy rates are “like the stock market,” he said, bound to go up and down. “To me, the more important thing is the amount of trash that I’m seeing in my Big Belly trash cans on the corner, giving me indications every night and every morning. The trash indicators are trending up steadily.”

Vacancy, and the love of the local bodega

Commercial vacancy rates increased citywide from 2019 to 2020, according to the most recently available data from the New York City Council, with communities in Midtown, Lower Manhattan and northern Brooklyn taking the biggest hits.

Brewer’s December 2021 survey identified 48 dark stores in Manhattan, 42 in Brooklyn, 17 in Queens, seven in the Bronx, and just one on Staten Island. Before quick-commerce delivery companies started to close en masse earlier this year, most prided themselves on their rapid expansion, which included taking over commercial spaces left vacant by the pandemic.

But now, the shuttered companies have vacated dozens of storefronts across the city. On Fourth Avenue in Park Slope, a former Fridge No More location is still plastered with advertisements. The company closed abruptly in March.

Chen said he felt the “dark stores,” with their windows blacked-out and inaccessible, are likely making neighborhoods struggling with retail vacancy feel even less welcoming. But, he said, he would leave the decision to change the appearance of the stores up to the businesses themselves.

Demand dictates which businesses will be successful or not, Chen said, and delivery apps offer a specific service. The businesses in the city and in Chinatown will fluctuate based on what the community wants and needs, and there’s no way to control that. But he believes that after months and years of being stuck at home, most people are ready to forego delivery and head back out.

“They want to have a communal experience, and Chinatown is well-meant for a communal experience,” Chen said. “The meals are meant to be communal, it’s meant to be piping hot, even if you do the choice between quick delivery and sitting here — I would say it’s sitting here.”

Mubarez said bodegas have “proved our worth” for the community by staying open and accessible to their neighborhoods during the pandemic. The community has stuck with them, he said, and many are thriving.

“A lot of people want to name something the heart of the city,” he said. “For me, this is a little cheesy, but I think bodegas are the veins of the city. They’re interconnected all throughout the city … what they’re doing is they’re pushing life everywhere throughout the city.”

A new delivery service isn’t enough to dissuade people from returning to their local corner store for a few items or for a midday sandwich, Mubarez said, especially when a store has been running in the community, making connections, for years.

“If there’s any businesses out there thinking of revolutionizing or improving the bodega and convenience space, really reach out to our community members,” he said. “It’s not great news that a company had to shut down. Employees there might have quit their old jobs, invested into this new business, and now it’s failed. Really put in the work to speak with the people who are already in this space, who are already in tune with the community.”

Join amNY over the next several weeks as we explore the impact quick-commerce delivery services have had on local businesses and neighborhoods; how the rise and fall of the companies has affected the thousands of delivery workers in New York City; how legislators are stepping in; and more in Still Racing to Deliver.