I’m gonna kick some COVID-19 butt!

On Friday, I gave a pint of plasma at New York Blood Center, a yellowish clear liquid extracted from nearly an hour of blood going from my arm into a machine that then returns the unused red blood cells back to my body. It ends with a cold saline solution chaser – I’ll have that on the rocks, please.

The 600ml of plasma they extracted could be used on three patients with COVID-19 and possibly lead to recovery. My super-powered anti-bodies will be put to work elsewhere, having helped me fight off the dreaded novel coronavirus in two days, that has killed so many thousands — including my colleague Anthony Causi, 48, who left behind a wife and two young children.

Friday morning, I got up way too early with the child-like anticipation that I could make a difference. I’m betting the other people who were at the New York Blood Center in Grand Central’s MetLife building felt the same way.

The streets of Manhattan were again eerily quiet — almost no vehicle traffic, a few stray masked strangers walking to a job. Homeless people continued to camp out on corners or in doorways, nobody scooting them away as nobody was there to bother them. One woman had a multitude of umbrellas set up like a lean-two keeping warm in the chilly spring air.

At the corner of 42nd Street and Sixth Avenue next to Bryant Park, six heavily armed counterterrorism cops and their K-9 German shepherd partner stood looking bored – their dog peering quizzically at them with cops nose and mouth covered in surgical masks. The officers’ badges were draped with a black mourning band in memory of 27 NYPD members killed by coronavirus.

Nearby, a homeless man sat looking for change, a sign announcing “a humiliated army vet – please help.” People stopped for a quick bite at McDonald’s near him, one of the rare stores open, but practicing social distancing with no tables. Patrons fearfully rushed past the homeless man as he huddled on the ground.

In Grand Central, only the 42nd Street entrance to the massive station was open just off Vanderbilt Avenue. If a pin dropped, you’d here it bounce off the cavernous walls.

A group of National Guardsmen wearing their PPEs, crowded in a corner complaining about how their own families were dealing with sheltering in place.

Finally, I arrived the Blood Center, along with another donor. We waited at the door for an attendant to allow us in.

“Do you have an appointment? Are you feeling ill today?” we were both asked, A disposable thermometer – a thin strip of plastic with a small computer chip – was then handed to us for a quick fever check. I told her I hadn’t had symptoms since March 15 – donors must be without symptoms at least 14 days before donating.

I entered with a young woman, a speech pathologist who said she had the virus a while ago and had “very light symptoms.” The Queens resident seemed to be smiling broadly under her flowery mask: “I just want to make a difference,” she said.

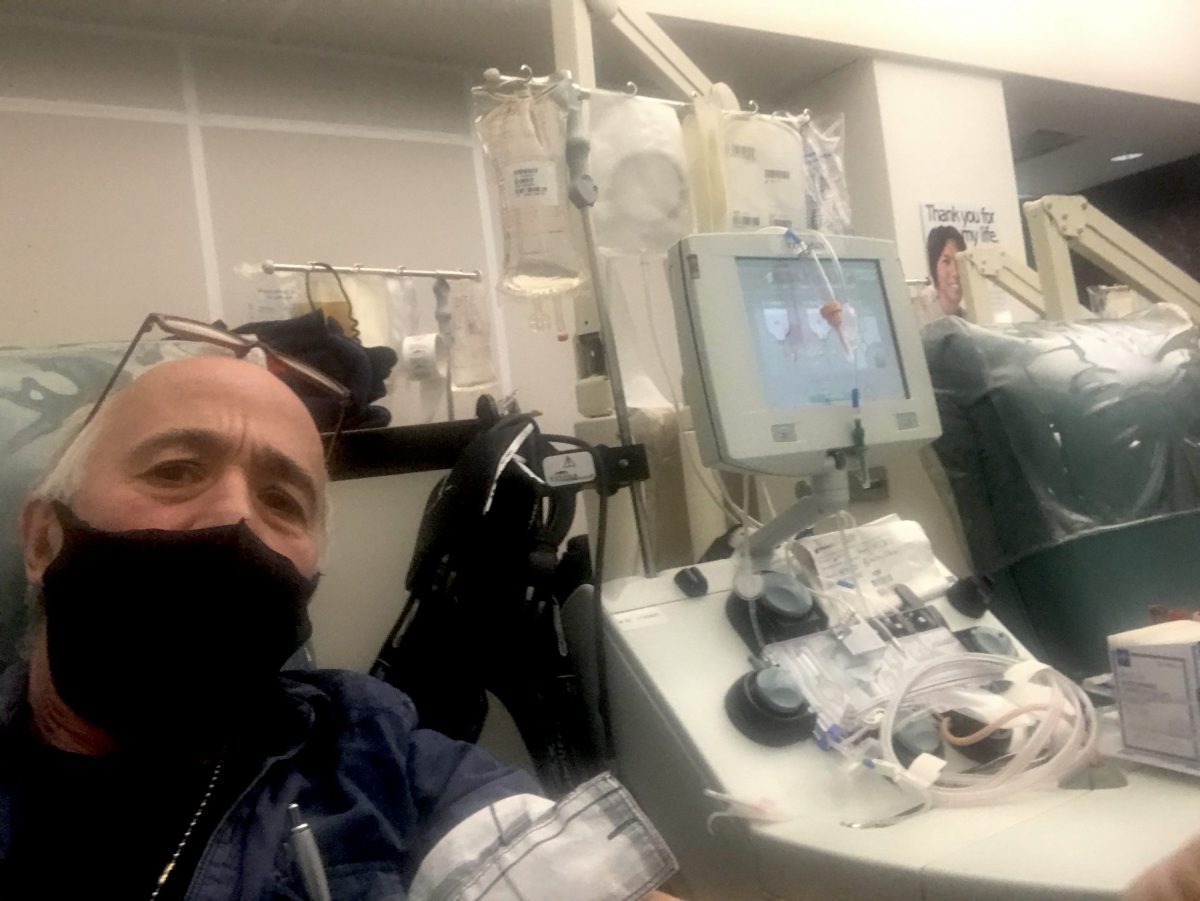

After a series of questions — not to mention being asked if I was feeling ill about three more times — I was led into a room with sea-foam blue stain resistant-cushion loungers next to odd looking machines called Apheresis, a centrifuge type machine that separates plasma from blood. A flashing computer monitor checks the ebb and flow of the blood.

A heavily tattooed, tough looking brown-haired woman was relaxed in her chair, tubes running from her arm. She toyed with her cell phone, while keeping her other arm still and her hand flexing to help pump blood into the machine. Her vest was marked, “NYPD, Cold Case Squad.”

I was led to one of the lounge chairs, rolled up my sleeve and was ready for my donation. The attendant, a surgical-masked West Indian woman with steely eyes, looked for a good vein. “Either arm would do,” she said.

The attendant then inserted the needle with a twin tube on it connected to the blood separator Aspersis that takes the blood from your arm, separates the plasma from it, and then returns the red blood cells back into your body. I had to grip a black cylinder wrapped in paper towel, lightly squeezing it during the pumping process.

While I was there, a young man in spectacles, wearing beige khakis and a red sweatshirt, was intently staring at his iPhone glowing on off his glasses. His surgical mask occasionally slipped from his nose before he carefully adjusted it while keeping track of a glowing screen that fluctuated from “draw” to “return.” On “draw,” you lightly pump your clench your fist; on “return,” you relax.

One couldn’t help but keep watching the screen on the Asphersis machine, because if you moved your arm in any way or didn’t clench your hand enough, the draw would lose pressure and an attendant would walk over to reset to increase the flow. So keeping track of the screen was essential to finishing quicker – no time for Netflix here.

After about an hour, which seemed to go rather quickly considering the monotony, with occasional sneak-peak at my cell phone, the machine beeped, signaling that 600ml of solution had been collected – enough to treat three people for COVID-19 or other illnesses that afflict people.

A rinse then began, turning my arm oddly cold from the fresh saline cleaning the lines and my veins.

I was hungry, so the goodie bag contained Lorna Doones, Oreos, bags of chips and pretzels, and a bottle of apple juice to wash it down in a lounge area – table for one. Sorry, no lollipops.

Blood Center spokesperson Jennifer Barden said they have had a good response for donations of plasma and blood from New Yorkers, already collecting 2,000 doses of plasma and they expect to ramp up to 6,000 per week. The New York Blood Center is expanding to more locations; there were no facilities in my hometown of Brooklyn at the time of my appointment.

The plasma at first was being used in clinical trials, but now are being used by hospitals including Mount Sinai, Columbia Presbyterian and Montefiore Medical Center. Soon, any hospital with Food and Drug Administration approval can request plasma from the Blood Center.

Dr. Christopher D. Hillyer, president and CEO, of New York Blood Center encourages New Yorker’s to donate plasma and blood to help others.

“Our region was hit early by this pandemic and has sadly suffered from the highest number of infections in the nation,” Hillyer said. “That means we now have the largest pool of recovered patients who can become donors and help those who are severely ill. New York Blood Center is uniquely positioned to collect and maintain a robust public bank of convalescent plasma that can serve hospitals in our immediate area and throughout the country. We are asking all eligible donors to come forward so we can treat as many patients as possible.”

Founded in 1964, NYBC is one of the largest independent blood centers in the world. Its network serves local communities in New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, Missouri, Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska and Rhode Island. NYBC anticipates collecting convalescent plasma collections across these locations and the pandemic intensifies in locations across the US.

To get an appoint, go the NY Blood Program website at nybloodcenter.org/donate-blood/covid-19-and-blood-donation-copy.