When babies are born with HIV, starting treatment within hours to days is better than waiting even the few weeks to months that’s the norm in many countries, researchers reported Wednesday.

The findings, from a small but unique study in Botswana, could influence care in Africa and other regions hit hard by the virus. They also might offer a clue in scientists’ quest for a cure.

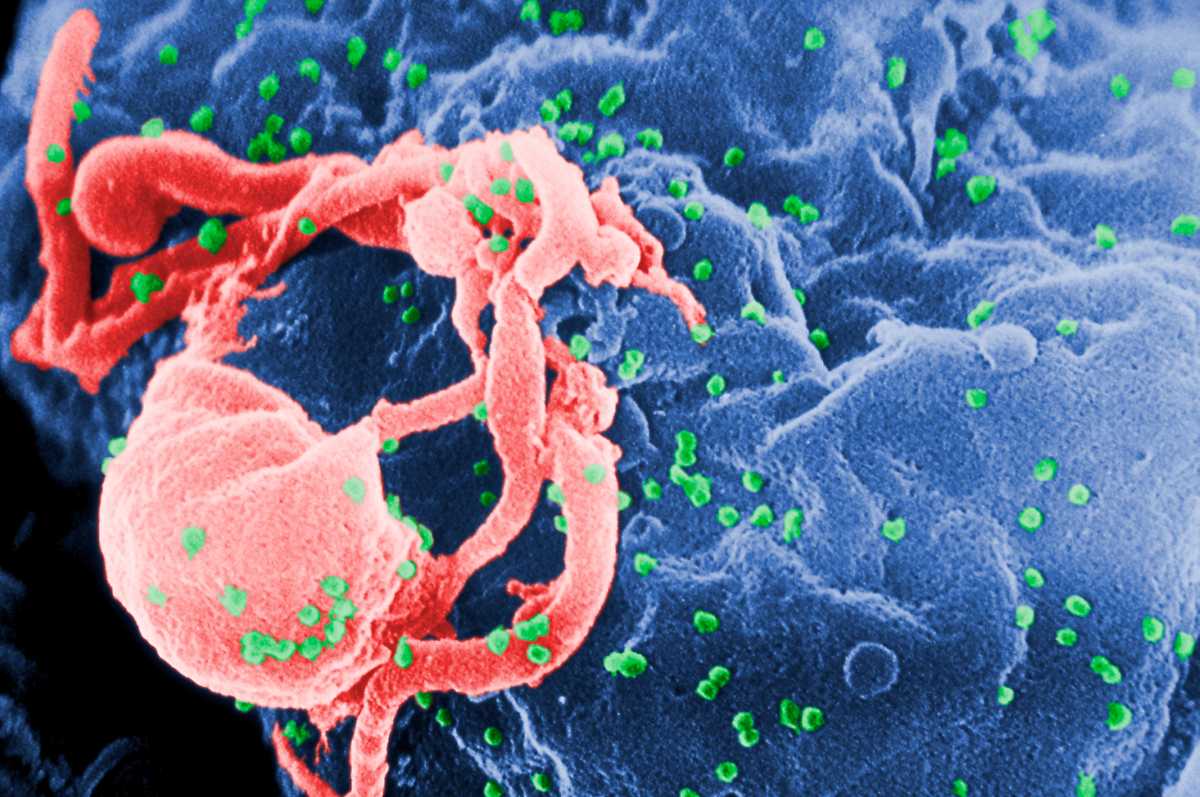

The Harvard-led team found super early treatment limits how HIV takes root in a newborn’s body, shrinking the “reservoir” of virus that hides out, ready to rebound if those youngsters ever stop their medications.

“We don’t think the current intervention is itself curative, but it sets the stage” for future attempts, said Dr. Daniel Kuritzkes of Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who co-authored the study.

Giving pregnant women a cocktail of anti-HIV drugs can prevent them from spreading the virus to their unborn children, a step that has dramatically reduced the number of babies born with the virus worldwide. Still, some 300 to 500 infants are estimated to be infected every day in sub-Saharan Africa.

Doctors have long known that treating babies in the first weeks to months of life is important, because their developing immune systems are especially vulnerable to HIV. But an infant dubbed the “Mississippi baby” raised a critical question: Should treatment start even earlier? The girl received a three-drug combination within 30 hours of her birth in July 2010, highly unusual for the time. Her family quit treatment when she was a toddler — yet her HIV remained in remission for a remarkable 27 months before she relapsed and restarted therapy.

The Botswana study was one of several funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health after doctors learned of the Mississippi baby, to further explore very early treatment.

The findings are encouraging, said Dr. Deborah Persaud, a pediatric HIV specialist at Johns Hopkins University who wasn’t involved with the Botswana study but helped evaluate the Mississippi baby.

“The study showed what we hypothesized happened in the Mississippi baby, that very early treatment really prevents establishment of these long-lived reservoir cells that currently are the barrier to HIV eradication,” Persaud said.

She cautioned: “Very early treatment is important, but prevention should still be our top priority.”

In Botswana, researchers tested at-risk newborns, enrolling 40 born with HIV, treating them within hours to a few days, and tracking them for two years. On Wednesday, they reported results from the first 10 patients, comparing them with 10 infants getting regular care — treatment beginning when they were a few months old.

Medication brought HIV under control in both groups. But the children treated earliest had a much smaller reservoir of HIV in their blood, starting about six months into treatment, the researchers reported in Science Translational Medicine.

The earliest-treated children also got another benefit: more normal functioning of some key parts of the immune system.

One big question: Did the HIV reservoir shrink enough to make a long-term difference? To find out, next year the researchers will give these children experimental antibodies designed to help keep HIV in check, and test how they fare with a temporary stop to their anti-HIV drugs.

In the U.S., Europe and South Africa, it’s becoming common to test at-risk infants at birth. But in most lower-income countries, babies aren’t tested until they’re 4 to 6 weeks old, said study co-author Dr. Roger Shapiro, a Harvard infectious disease specialist.

— Lauran Neergaard