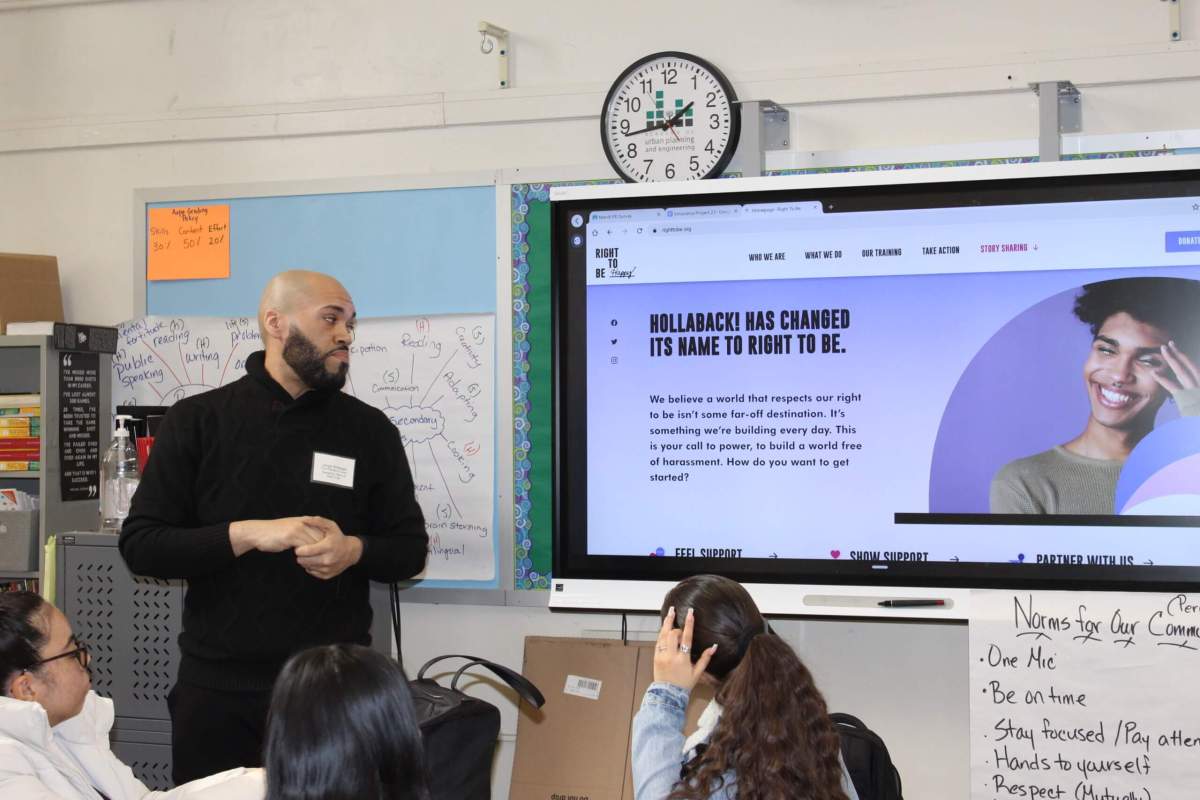

High school students at a Brooklyn school are learning how to intervene when they see bullying and harassment at school and on the streets.

The Academy of Urban Planning and Engineering (AUPE), formerly Bushwick High School, has partnered with anti-bullying nonprofit Right to Be since last September to equip teachers with a curriculum that trains people how to be better bystanders when they witness a situation.

Jorge Sandoval, the principal of AUPE, told amNewYork Metro that partnering with Right to Be was a sensible decision to make after seeing behavioral concerns arise when students returned to in-person classes after the initial peak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I had to jump on this opportunity to educate my students so they can make better decisions,” Sandoval said. “It teaches them not to be an aggressor, not to be caught up in the “he said she said,” and not to just react with physicality and words.”

Sandoval said AUPE often uses restorative justice practices to address any situations where negative student behavior is a concern. AUPE is a relatively smaller school of 400 students who are predominantly Latino and Black. About 100 students have already or are currently being taught the bystander intervention training by teachers in their classes.

Right to Be, previously called Hollaback!, started as a conversation between a group of women who all experienced various forms of harassment in the workplaces and streets of New York City. The nonprofit, along with Cornell University, led the largest international study on street harassment in 2015, and from there, the movement has grown as the nonprofit leads bystander intervention trainings for hundreds and thousands of people, including students, every year.

The trainings provide modern-day instruction on how to deal with bullying and harassment for both general audiences and specific communities, including Black, Latinx, Asian, Jewish, Muslim, LGBTQIA+, neurodiverse, and disabled people. The curriculum can be geared towards workplace, street, online, or school harassment and bullying incidents.

Sandoval likes being able to give feedback to Right to Be on the impacts on students and said the opportunity could lead to building student leadership around bystander intervention so that students could perhaps “go on and even work for the organization.”

“We can get student trainers from this project to go out and spread the word, spread the message, and spread the movement,” Sandoval said.

Rosie Flore, who teaches ninth grade global history and theater at AUPE, was approached by Sandoval to introduce the bystander intervention training to her students. Flore agreed and first introduced the new curriculum to her theater students, which she said was a natural fit.

“There’s a lot of scenarios that we get to look at and think about, which is so similar to how we do improv in class,” Flore told amNewYork Metro.

Flore teaches bystander intervention every day, and has decided to use the full class period of 50 minutes for the instruction. She said teachers have the option to tweak and choose the length of the training depending on their class needs and schedules. But Flore said she’s found that teaching the full-length curriculum has led to visible changes in her classrooms.

She might see an incident building in the classroom, for example, and has then heard the language of the curriculum being used in some of those situations. There are now many students using the bystander intervention vocabulary to identify when bullying and harassment is starting, which she has had never seen previously, Flore said.

“I’ve really seen a lot of growth,” Flore said. “It manifests in really small ways.”

Flore said that she hopes that the bystander intervention culture “will just build upon itself” and that students who are really passionate about being better bystanders will go on to create an initiative or a club so that the rest of the school can experience a culture shift.

Emily May, the president and co-founder of Right to Be, told amNewYork Metro that the nonprofit has been teaching and fine-tuning its bystander intervention trainings for middle and high schools across the country.

“I think our bullying education system is pretty broken,” May said. “Young people are struggling with harassment and normalizing the harassment they’re facing. They are not necessarily associating the racism or sexism or homophobia that they’re coming across as a form of bullying.”

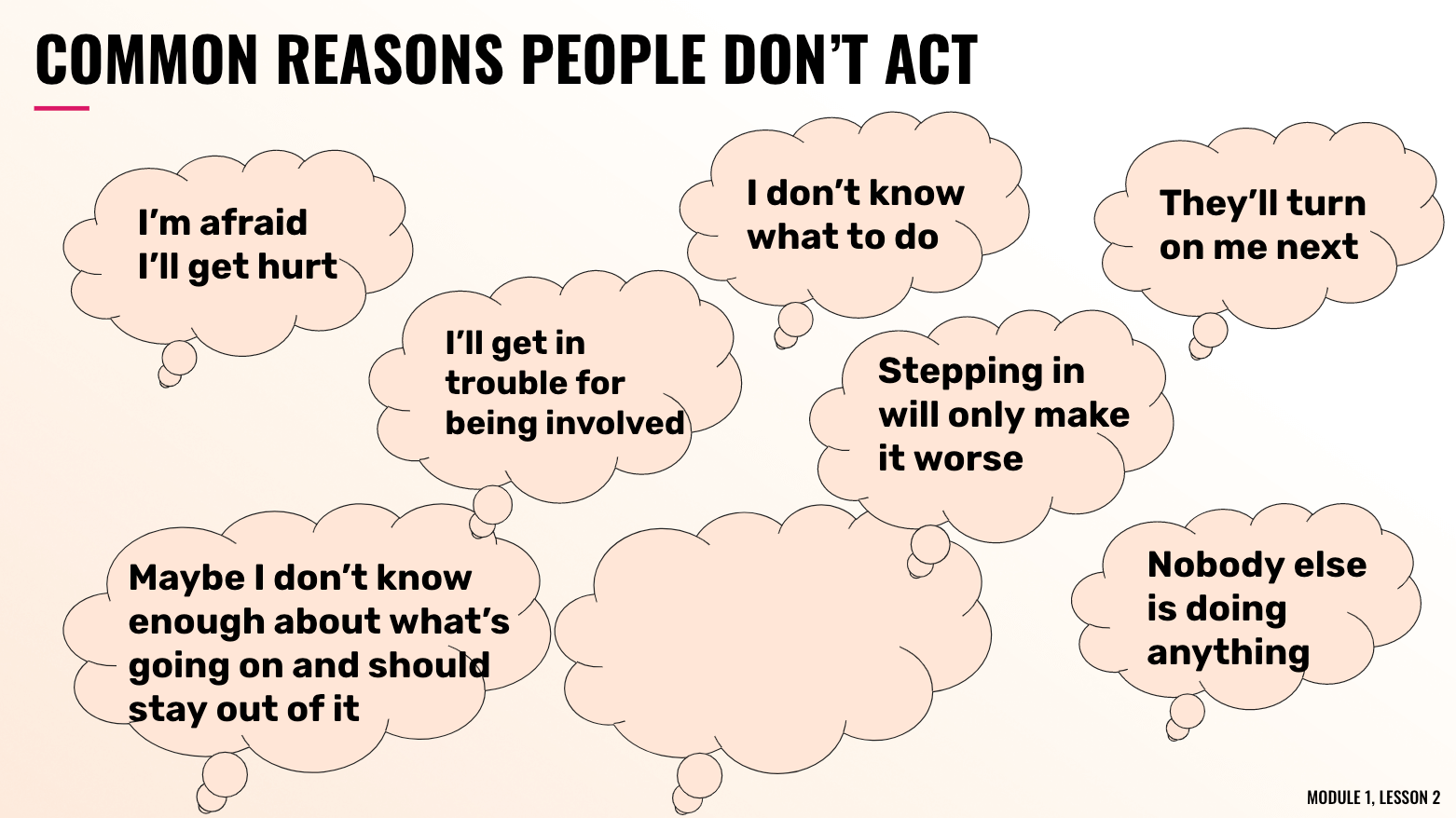

She initially thought that principals would have security and safety concerns around training students how to intervene in potentially risky situations. There was and still is a stereotype that bystander intervention involves putting your safety at risk, May said.

What she learned from principals, instead, was that students were sometimes already intervening on their own, but doing so in ways that could put them in harm’s way, through “quick, fiery escalation with aggression — strong words and potentially even threats that can escalate quickly into violence.”

“They’re doing it in ways that are dangerous,” May said. “We felt like we needed to address this.”

May pointed to poor examples of bystander intervention from television, video games, and movies and from these, people mistakenly assume that “either you hang your head and walk in silence, or you get super aggressive.”

To combat this, Right to Be offers two-session bystander intervention trainings for schools, including the seven-week curriculum being piloted at AUPE. The first session trains students on identifying harassment and bullying and what incidents could feel like from the perspective of people from diverse racial and cultural identities.

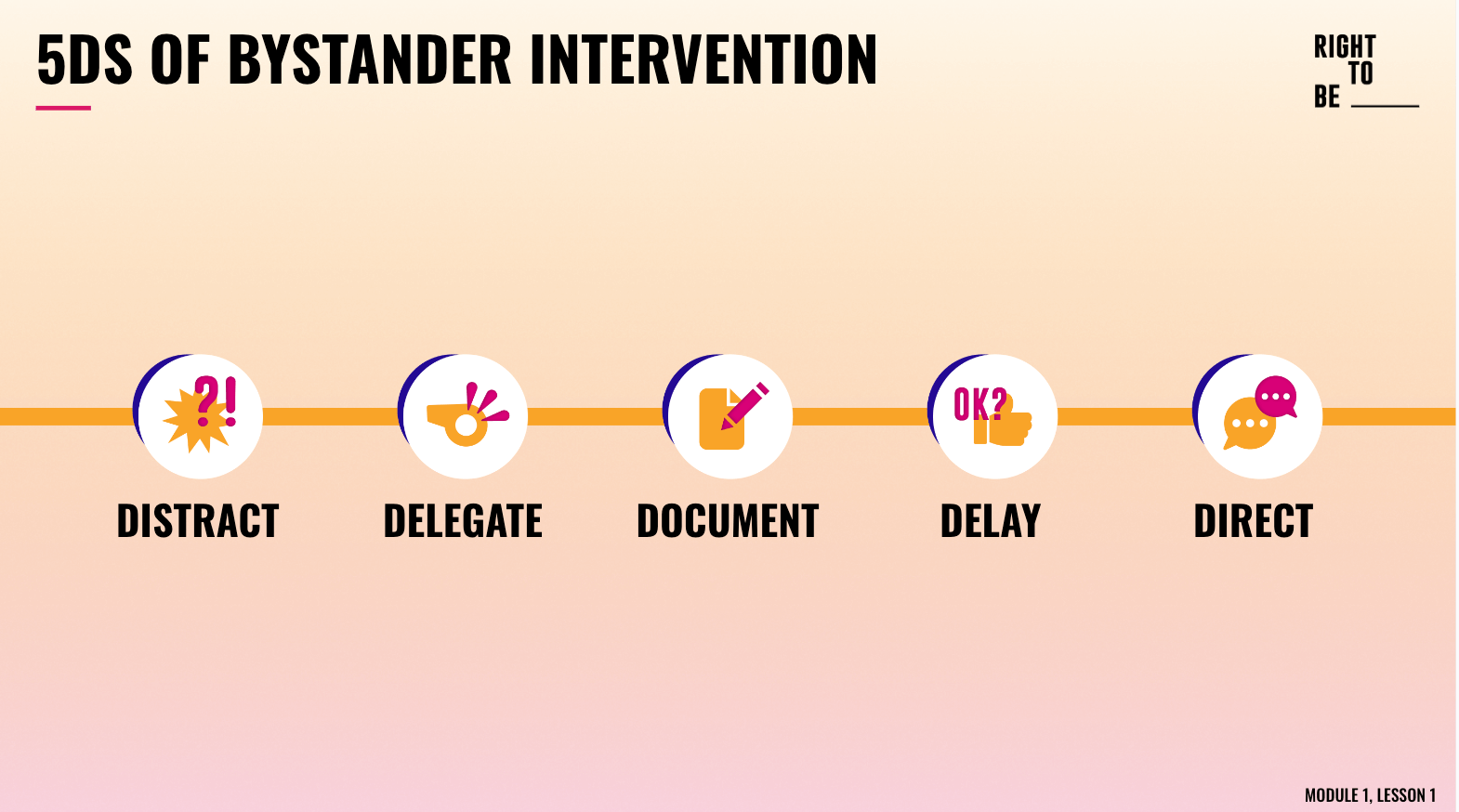

The second session teaches Right to Be’s “Five D’s” (Distract, Delegate, Document, Delay, and Direct) and how students could use them in real-life situations.

May said Right to Be understands that relying solely on police and armed security to deal with bullying and harassment can perpetuate distrust and harm in vulnerable communities and with people of color, particularly Black and Latinx people. She said the training is meant to prevent the criminalization of harassment.

“That being said, I think the role of security guards can be useful potentially in a delegate situation,” May said. “Part of the curriculum is about checking in with a person being harassed before you make a move like that.”

She elaborated by saying that the training deals more with day-to-day forms of harassment, and understandably so, if a situation is escalating into violence, the people involved will most likely feel too unsafe to directly intervene and pass it, or “delegate” it to someone who is better equipped and trained to deal with violent situations where there may be weapons and great physical harm involved.

May is hoping the movement to educate youth will continue to spread across more school districts, and pointed to New York City leading efforts to do so.

“We want to see this happening similarly with youth,” May said. “To our knowledge, New York City is the first place to try it.”

Councilmember Crystal Hudson (D-35) introduced a resolution on April 11 calling on the New York State Education Department to mandate bystander intervention training for all staff, educators, and students, as well as annual training for middle and high school students and resources for parents. Hudson has been working most closely with Right to Be as advisors on getting bystander intervention training into New York public schools.

Hudson told amNewYork Metro that for years, there have always been discussions and work around combating bullying, but the one piece that’s been missing is actual bystander training so both kids and adults can stop bullying in its tracks when they see it or recognize that it’s happening.

“What we’re doing is saying let’s train everyone in a school community on how to identify bullying, how to safely and appropriately intervene,” Hudson said. “They can nip it in the bud right then and there so that police and other authorities don’t have to necessarily be called in.”

Statistics and victim testimonies at city hearings all point to bullying continuing to be a deep, pervasive issue in schools across New York. There was a record high of more than 10,800 reported incidents of bullying/cyberbullying, harassment, and discrimination in New York State during the 2019-20 school year, according to New York State Education Department data.

There is also the issue of underreporting incidents across New York City schools. New York State Comptroller Thomas P. DiNapoli found in an audit published in 2019 that New York City’s Department of Education wasn’t doing enough to report bullying, harassment, and discrimination, and that there appeared to be conflicting definitions of what “bullying” constituted.

Hudson referenced the Dignity for All Students Act, enacted in New York State in 2010 to ensure a safe school environment for students, free from discrimination and harassment. Hudson hopes that her resolution could broadly address all types of bullying and lead to a healthier environment for students.

“We know the negative impacts and effects that bullying can have: kids’ academic performance being impacted by bullying, dropping out of school, and overall mental health from bullying,” Hudson said. “By having folks trained in intervention, I think we will see a lot more intervention happening and hopefully a lot less bullying.”

Kelly Erickson, director of instructional design and innovation at Right to Be, has been overseeing the AUPE pilot program. Erickson told amNewYork Metro that the curriculum goes deep into scenarios and practices that look at all the nuances of bullying and harassment — something she said formal definitions of bullying don’t quite capture.

“There is a legal definition for what constitutes bullying and what constitutes harassment,” Erickson said. “But below and beneath that are things that happen before it meets that formal definition, such as disrespect.”

The curriculum is meant to empower students and victims on how to safely and appropriately respond to even the “tiniest little microaggressions,” or small instances of disrespect, which could eventually snowball into larger and more problematic situations.

From the pilot program, Right to Be will continue refining its curriculum so that more schools and teachers can use it, whether its the full 20-lesson curriculum that can take up to eight weeks to teach, a medium version of 10-12 lessons, or a small version of five to six lessons.

Born and raised in Bushwick, Jorge Arteaga told amNewYork Metro his experience attending Bushwick High School and the bullying and discrimination he faced there paved the way for him joining Right to Be in 2019. Arteaga is now the vice president of lead operations officer at Right to Be and has led bystander intervention sessions — particularly on police-sponsored and anti-Black harassment — at his high school alma mater.

“Growing up for me, anti-bullying was a thing that you heard about in suburban schools,” Arteaga said. “In a city school, you kind of just deal with it.”

Arteaga said bystander intervention training is pivotal for a school like AUPE, where there is a large population of low-income, Black, and brown youth. He said there has been a huge amount of support from the principals, teachers, and the school’s social worker.

“It was important to start here in our community, where there are Black and brown young boys trying to figure out how to show up in this world in a meaningful way,” Arteaga said.

When he was a student at Bushwick High School, Arteaga remembers situations that would quickly erupt and escalate into violence and huge fights. Gang members from the Crips, Bloods, and Latin King once attended Bushwick High School before the school was closed and multiple new schools, including AUPE, replaced the campus.

Said Arteaga: “There was gang violence, inexperienced teachers who couldn’t handle their classrooms, and the socioeconomic statuses of many of the students, as well as a hyper-aggressive “machismo” culture, which promotes a dominant, prideful masculine approach to life.”

Arteaga pointed to several different approaches to bystander intervention that he himself appreciates: Delay, in its ability to provide support for a victim; Delegate, in its initiative to get more people in the community involved; and Direct, which he called his personal “superpower” which is directly addressing the situation without making the situation worse — an ability he credited to the women in his family who raised him.

“We’re all here to achieve the same thing, which is to equip our youth with skills and strategies to just be amazing humans and treat each other with respect,” Arteaga said. “The sooner we can teach youth how to enter into conflict with each other, the better off we’ll be.”