History and social studies curriculums in New York public schools could soon expand to become more diverse and inclusive, with many advocates and community leaders saying it’s about time.

State Senator John Liu (SD-16) and Assemblymember Grace Lee (AD-65) have co-sponsored a bill mandating the inclusion of Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) curriculum in social studies or history courses at public elementary, middle, and high schools across New York state.

Liu said that the new curriculum would directly address the fact that “Asian Americans have been scapegoated for everything from global pandemics to economic recession to international conflicts” and the way to eradicate anti-Asian hate for the long term is by educating students “so that they understand that Asian Americans have been a part of building America as much as anybody else has been.”

The curriculum would look at the “great deal of struggles as well as accomplishments” that Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders, and Native Hawaiians have faced in the United States.

Asians are the fastest growing racial group in the United States, yet Asian Americans were among the least likely racial groups to feel that they belonged and were accepted in the United States, according to the 2023 STAATUS Index, a national study of Asian Americans and the attitudes and stereotypes around this demographic.

Specifically, 80% of Asian Americans do not fully feel that they belong and are accepted, and 50% of Asian Americans feel unsafe in the United States, especially on public transportation.

Liu said that he himself remembers “some mention of Chinese immigrants building the railroads and Japanese Americans being thrown in prison during World War II” while he was a high school student at The Bronx High School of Science, but that the true education began when he was in college and served a leadership role in the Asian Student Union at Binghamton University.

“That set the groundwork for me running for office,” Liu said, of that college experience. “The understanding of the model minority myth, the perpetual foreigner syndrome, the fear mongering of yellow peril. Those are all things I learned in college, and not even in coursework, but through student activism.”

But the curriculum left out much of significant historical events over the timeline of past and present U.S. history: “No mention of Vincent Chin. No mention of the post-911 attacks against South Asians. No mention of over 20 years of Chinese Americans being accused of spying for China.”

Liu said that another reason why the curriculum is needed across New York schools is to reduce the perceived narrative that communities of color are always in conflict with one another.

“There’s a great deal of Asian Americans and other communities of color working, sometimes fighting, alongside each other,” Liu said. “But there seems to be too much in media nowadays that has the effect of driving a wedge between Asian Americans and other communities of color.”

But how would this curriculum stack up in schools that are heavily STEM-focused? Liu said that “every student has to have the appropriate amount of history courses in order to graduate, even from all the specialized high schools in New York” so this curriculum would be included in that.

Liu pointed to several key partners in the bill initiative, including Mayor Eric Adams and the REACH Coalition, an advocacy group formed in 2022. Liu praised Adams for including Asian American history and experience in New York City public schools in advance of the proposed statewide mandate. Adam’s citywide mandate is set to expand AAPI curriculum into all New York City public schools this coming September.

“(Adams) didn’t wait for a statewide mandate, which is what my legislation is about,” Liu said.

The REACH Coalition formed in 2022 to advocate for Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander history to New York schools. The coalition, co-led by the Coalition for Asian American Children and Families (CACF) and the New York chapter of the Organization of Chinese Americans, is comprised of more than 170 community leaders, parents, students, and educators, as well as more than 60 organizations.

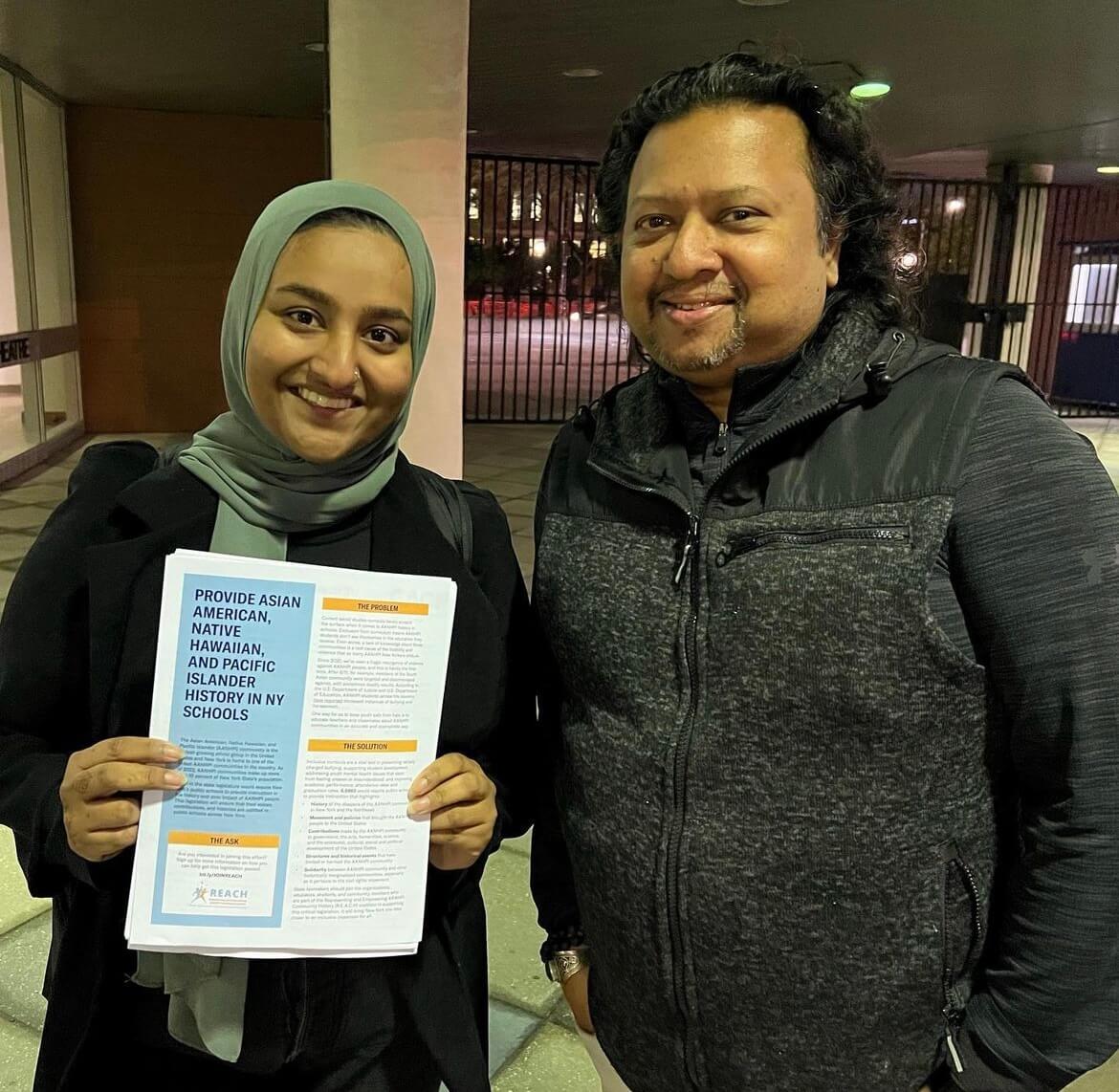

One of the primary goals of REACH is to advance legislation to ensure that AANHPI history is taught in schools, CACF spokesperson Winnie Kong told amNewYork Metro. For the past few months, REACH Coalition has been working with Senator Liu and Assemblymember Lee’s office to advocate for the integration of AANHPI history into existing social studies curriculum.

Kong said that the coalition is especially proud of its advocacy efforts that ensured the bill language included Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, as well as a curriculum that teaches the history of solidarity between AANHPIs and other communities of color.

Kulsoom Tapal, the education policy coordinator at CACF, told amNewYorkMetro that the coalition isn’t asking for an elective or an extra, separate course to teach AANHPI history.

“All we’re asking is that we ensure that AANHPI voices are represented throughout the curriculum in the existing social studies classes that students are taking,” Tapal said. “We don’t want it to be something that’s optional or something that’s an elective.”

Tapal said that the current curriculum teaching Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander history is “missing a comprehensive discussion on cross-racial solidarity communities of color — especially between African American and Asian Americans.

“You maybe learn about the Chinese Exclusion Act and maybe vaguely learn about the Japanese internment camps,” Tapal said. “But how many folks are learning about AAPI contributions to the Civil Rights Movement fighting alongside Black activists and learning from Black activists?”

Any mention of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander history is also just nonexistent at this point, Tapal pointed out.

Angela Li, who was born in Manhattan’s Chinatown, remembers how she entered high school feeling “imposter syndrome.” Li was raised in China for several years before returning to New York City at the age of five as an English language-learning student.

It was only when she encountered Asian American literature in a few of her classes that she finally felt a sense of belonging and recognition. Her first exposure to her culture and history within an academic setting was in the eighth grade at Hunter College High School in the Upper East Side, where she read Asian American literature, including Amy Tan’s “The Joy Luck Club,” a renowned novel about four young Chinese women living in America exploring their pasts and their relationships with their mothers.

“It was one of the first times our teacher turned to us and invited us to share how our identity and experiences connected with the texts that we read,” Li told amNewYorkMetro.

Li said that high school taught her how to navigate topics around socioeconomic class and race. She now hopes that more youth don’t have to wait until the end of middle school, like she had to, to learn more deeply about Asian American culture and history.

Her upbringing led her to pursue a degree in Asian American studies at the University of California, Los Angeles and then as an ethnic studies student at Columbia University. Li also works as a civic engagement coordinator at Immigrant Social Services, Inc., a nonprofit supporting immigrants in the Lower East Side and Manhattan Chinatown, and a member organization of the REACH Coalition.

“Being able to have spaces to talk about identity, I really wanted to continue to advocate for policy to uplift these communities,” Li said.

Li is now looking forward to the culmination of legislation to advance AANHPI curriculum in New York schools, especially as a first step to bringing people together and giving more youth the chance to feel empowered.

“I think it’s about time,” Li said. “It’s a sustainable and viable for long-term solutions to combat anti-Asian violence and hatred.”