Nearly 10,000 preschoolers with special education needs and disabilities in New York City did not receive their legally mandated services that the city’s Department of Education is required to provide, a report released Tuesday revealed.

The report, titled “Falling Short: NYC’s Failure to Provide Mandated Services for Preschoolers with Disabilities,” was released by Advocates for Children, a nonprofit that focuses on supporting students particularly from low-income backgrounds or vulnerable populations.

The new data analysis pointed to a major finding: that 37% of all preschoolers with disabilities — equating to 9,800 children — went the entire 2021-22 school year without receiving at least one of the types of services that the DOE was legally required to provide.

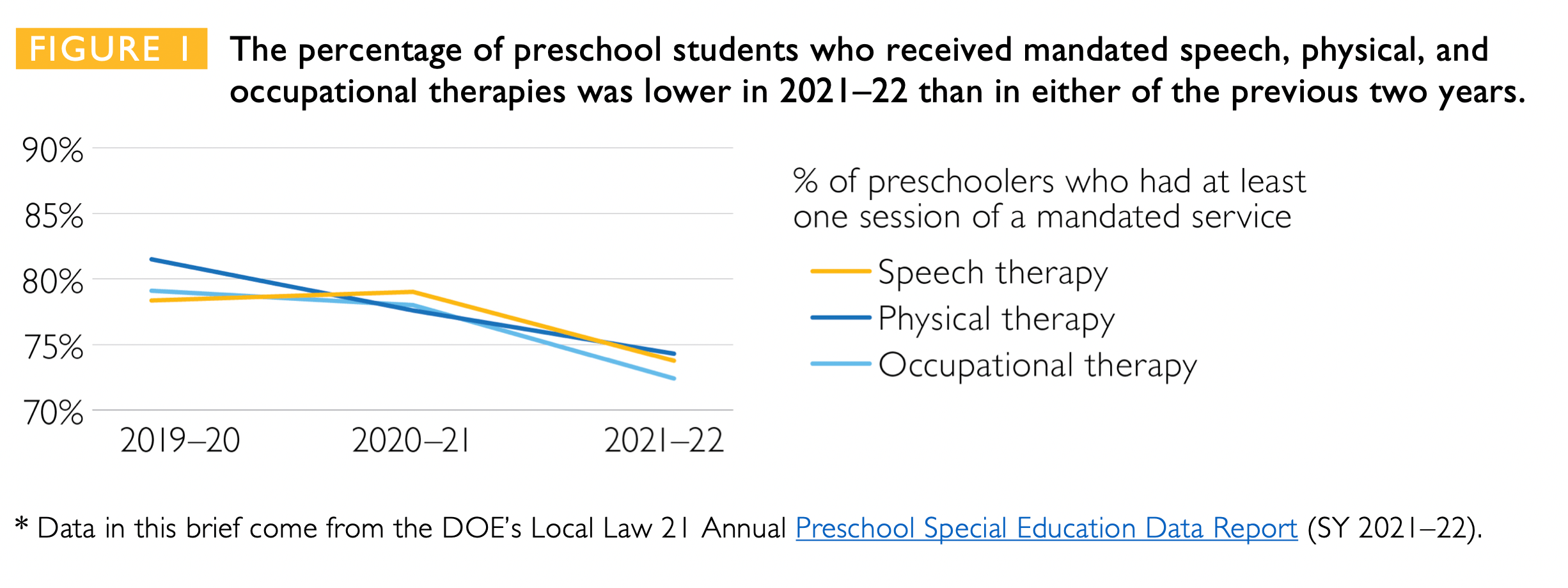

Roughly 28% of preschoolers citywide did not receive one session of mandated occupational therapy service in the 2021-22 school year, 26% did not receive one session of mandated speech therapy service, 26% did not receive one session of mandated physical therapy service, and 19% did not receive one session of SEIT services, according to the report.

The New York Citywide Council on Special Education acknowledged in its “New York Citywide Council On Special Education: 2021-2022 Annual Report” that the school year was a “disastrous and unfortunate year due to the ongoing public health crisis of the COVID-19 and its effect on the education of children in New York City schools.”

The report noted that the situation was stressful for all parents but especially for those of medically vulnerable students, especially since Individualized Education Program (IEP) meetings were mostly done online leading to “Glitches, hitches, dropped calls, frozen screens, lack of internet access or devices and the infamous phrase ‘you’re on mute’ caused delays and confusion for both staff and parents.”

The pandemic’s effect led to the number of students referred for special education evaluations dropping by 57%, the report stated. But even before the pandemic, almost a majority of students with IEPs were receiving only one of their mandated services, which the Citywide Council referenced in its report.

Kim Sweet, executive director of Advocates for Children, said in a statement that the mayor’s proposed budget cuts to education would further worsen the early childhood care and development and staffing crisis.

“Instead of cutting funding, the city must make the investment needed to hire enough special education teachers, service providers, and evaluators to meet its basic legal obligations to preschoolers with disabilities,” Sweet said.

The nonprofit concluded that the DOE is failing to meet its basic legal obligations to provide services to preschoolers with disabilities.

In response to the report, DOE spokesperson Nicole Brownstein said in a statement that the administration has acknowledged the shortcomings.

“We agree with the concerns of our parents and advocates that for far too long students with disabilities were excluded from programming and services,” Brownstein said. “This Administration is committed to righting this wrong. We are working to ensure that all students receive the services, supports, and resources that they need to succeed – from opening more special education seats in early childhood programs to hiring more staff across the system, we are prioritizing our students with disabilities.”

“Children are still not receiving the help”

The report highlighted several data points that break down the issue by the types of special education services — speech therapy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and special education itinerant teacher (SEIT) services — and the DOE’s compliance rates.

The compliance rates for the three of the most common services, speech therapy, physical therapy, and occupational therapy, “have been trending in the wrong direction,” according to the report.

More than 6,500 preschoolers who needed speech therapy did not have a single session of this service last year. One in five preschoolers never received their mandated speech therapy in 26 of the New York City’s 32 community school districts.

In Brooklyn, those noncompliance rates were even higher: In five Brooklyn districts, more than 40% of children in 3-K and Pre-K never received at least one of their mandated service types during the entire 2021-22 school year.

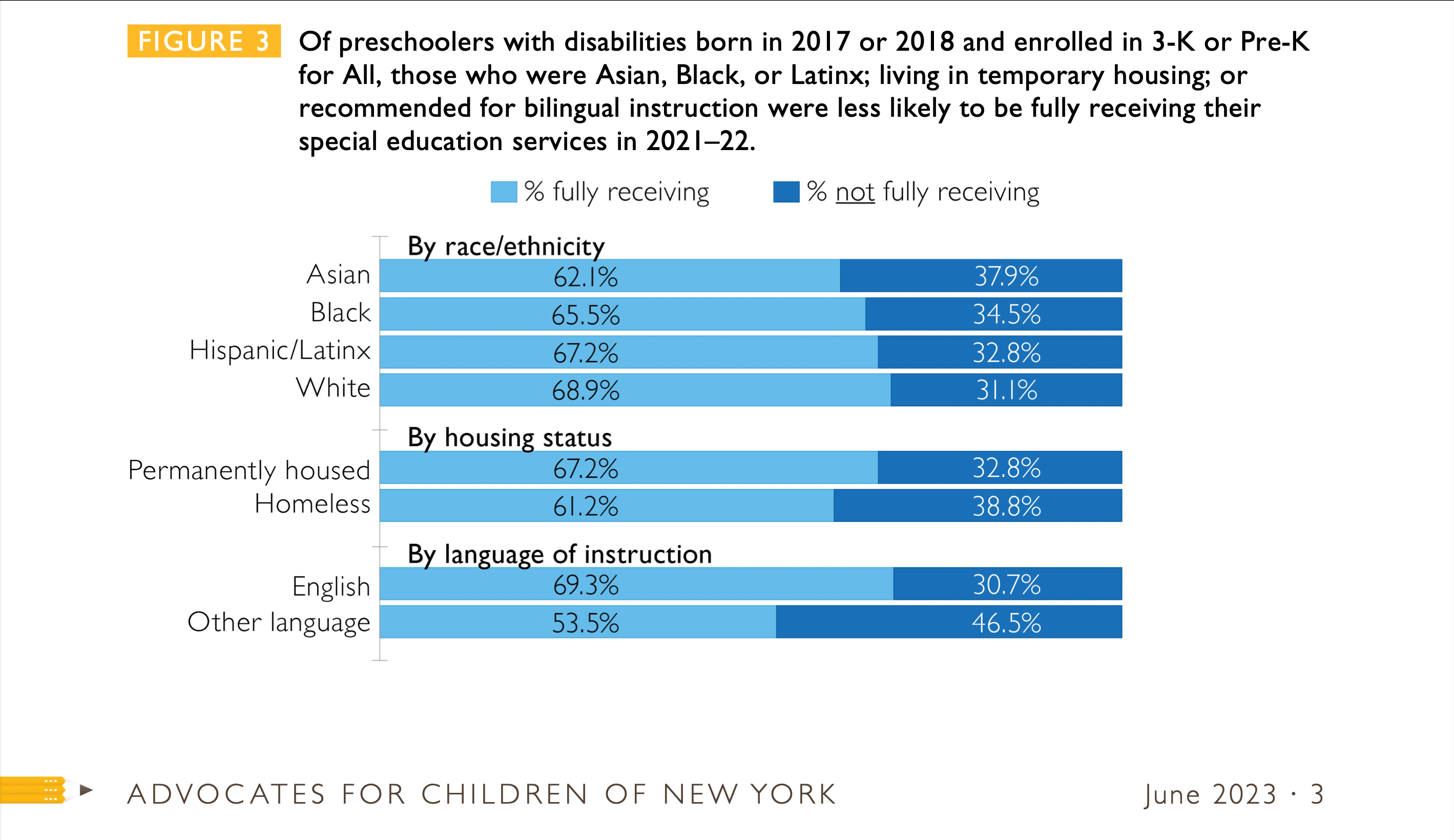

The data showed that Asian, Black, Latinx, preschoolers in temporary housing, or those recommended for bilingual instruction, were also less likely to fully receiving their special education services during the 2021-22 school year.

The issue is still indicative of a broader systemic issue. There were no school districts that fully served even 85% of its preschoolers with disabilities enrolled in 3-K and Pre-K for All programs, the data found. Yet 100% of such students are required by federal law, to receive them.

Moreover, these numbers likely understate the magnitude of the problem. For reporting purposes, the DOE considers children “fully” served if they had one session of a given service at some point during the school year, failing to capture children who waited months for their services to begin.

Jordan Bell, a father of a three-year-old, shared his experience with Advocates for Children of waiting months for a speech therapist to provide services to his son in his 3-K program. Bell had initially requested an evaluation for special education services for his son in April 2022. He was told Advocates for Children that he was told to wait until his son started 3-K.

“The school year is almost over and my son is still waiting for the DOE to find a speech therapist,” Bell said.

Even after the DOE acknowledged that Bell’s son needs speech therapy in January, the administration was unable find a therapist.

“Since April, I’ve been bringing my son to a school on Saturdays so he can at least get one of his two weekly speech sessions, but it’s just not enough,” Bell said. “My son is struggling to participate in class because it is hard for his teacher and classmates to understand him. I’ve asked the DOE for help again and again. If there aren’t enough speech therapists, then the city needs to hire more.”

Elizabeth is a mother of a three-year-old child with special education needs enrolled in a DOE-run 3-K program operated out of a daycare center in Community School District 13. She requested that her full name is not used out of privacy concerns.

She said her son has a genetic condition that causes multiple disabilities, qualifying him for speech therapy, occupational therapy, and physical therapy four times a week, as well as 10 hours a week with a SEIT, Special Education Itinerant teacher. Elizabeth told amNewYork Metro that after her son turned three last December and transitioned out of the early intervention program — “where he was actually receiving most of his services on his IEP — she’s now chasing down services for her son.

“On January 1, everything just went away,” she said.

While she acknowledges that starting services during the middle of school year is challenging, she said it’s been five months now, and her son still hasn’t received any of his speech therapy or physical therapy services. Her son was able to begin receiving an occupational therapy session once a week in April, but that was more by a stroke of luck when an occupational therapist at her son’s center opened a time slot.

“He has not received any speech and or any PT,” she said. “Trying to manage our child’s needs and our needs as parents, it is a lot of work and advocacy and stress.”

She’s tried to fill the gap by paying for private services, instead, which “there are obviously big financial constraints to that,” she said. Yet, she’s noticed the impact of these non-existent services has left an impact on her son.

“As best we can, we are fitting services for him in and around school and paying for them privately,” she said. “It’s more sporadic, now that we’re just trying to pay for and schedule private providers when we can make it work. We do feel like his progress has slowed and that’s difficult to see.”

Elizabeth’s response to the report brought more clarity to the situation and showed her how widespread the issue has really become.

“Seeing these numbers is really staggering,” she said. “I’ve come to realize we’re not alone in having trouble getting these services. It’s really tough to even fathom how this is going to improve. Honestly, it’s frightening.”

While Elizabeth said she was sympathetic towards special education contractors’ hectic lifestyles traveling from school to school, she thought of one way to address the inconsistent schedules.

“If there was any world in which these providers could be anchored or staffed to a particular school and have that flexibility, I think that would be the best case scenario for me,” she said.

“They would rather invest in a war chest than in children”

The DOE told amNewYork Metro in a statement that: “We expanded a team of itinerant NYCPS Occupational, Physical, and Speech therapists dedicated to serving preschool students in New York City Early Education Centers. This expansion included hiring an additional 24 Speech, 12 Physical and 23 Occupational itinerant therapists.”

Over the last three years, the DOE opened 21 Preschool Regional Assessment (PRAC) teams to provide additional evaluations beyond what is provided by New York State-approved evaluation agencies.

In 2022-23 school year, the DOE extended the hours of the PRAC team, which the administration said enabled more students to receive evaluations. The DOE stated that there are plans to extend those hours again for the 2023-24 school year.

Advocates for Children proposed several suggestions in its report to the DOE, including the city filling the gap when contracted agencies providing special education services fall short; addressing the shortages of adequate staff at private agencies; the DOE hiring its own preschool evaluators, service providers, and teachers directly; and increasing payment rates for contracted providers.

“There will be long-term ramifications for both individual students and for the city as a whole,” Advocates for Children stated in the report. “When preschoolers with disabilities do not receive the help they need early in life, many will require more intensive —and expensive — interventions once they reach elementary school.”

The nonprofit recommended that the city add at least $50 million to the Fiscal Year 2024 budget for preschool special education evaluations and related services.

Heather Clarke, a disability advocate and adjunct professor of special education and child development, told amNewYork Metro that the current crisis is why “there has been such a push from those of us who are advocates for pay parity” between DOE special education staff and special education contractors.

“It literally could take you months to get paid if you’re subcontracted,” Clarke said. “There were times when I was doing that work, I wouldn’t be paid for six months. You cannot survive like that.”

Clarke said this has become a huge issue in the city, especially in the recent year.

“I’m seeing it in real time because I’m going into the schools and seeing that there’s no special ed teacher, no speech therapist, no occupational therapist, no guidance counselor,” Clarke said.

Clarke also suggested that the city and the state partner with CUNY and build a “free pathway for people to become special educators, occupational therapists, speech pathologists, physical therapists.”

“We can take more than half of that money that (Adams) wants for NYPD and put it toward smaller class sizes, disability education, multilingual education, pay parity, and really invest in education,” Clarke said. “They would rather invest in a war chest for the police department than in children.”

Elizabeth, the mother of the three-year-old child in Community School District 13, noted the positive benefits of her son’s education in the early intervention program.

“He really responded to the frequency and the consistent schedule of meeting with these specialists almost every day,” she said. “We just saw so much progress when he was doing it consistently and frequently.”

The report highlighted the city opening new classes to serve nearly 700 children with more significant disabilities, but said the needs of more than 300 preschoolers are still going unmet and are still waiting for a seat in their IEP-mandated special education class.

Around 1,015 preschoolers who needed a small special education class were still waiting for a seat at the end of the 2021–22 school year.

“In recent months, we have heard from numerous parents who have been told by DOE Committee on Preschool Special Education administrators that there are simply no special education teachers or service providers available to serve their children,” Advocates for Children stated in the report.

In response to the report, Council Member Rita Joseph, who chair’s the Council’s Committee on Education, said she looks forward to partnering with the administration “to make sure there are enough service providers to meet the needs of every student with a disability.”

“It’s unconscionable that almost 10,000 preschoolers did not receive all of their special education services last year,” Joseph said. “We know this failure to support our youngest learners will only increase costs for the city in the long run, and we must act now.”