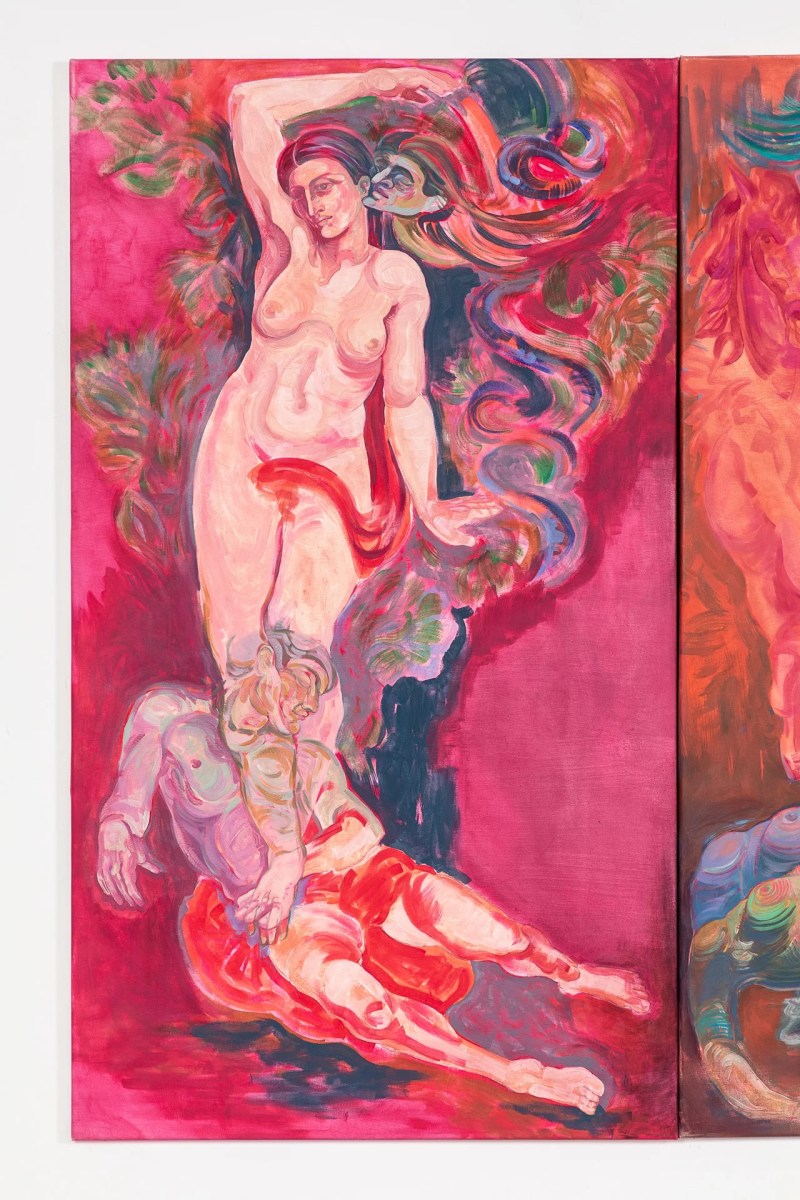

There is something otherworldly about Dara Maillard’s paintings. The figures—sinewy, shape-shifting, carved from fire and flesh—feel like they’ve crawled out of an old master’s fever dream, only to be reanimated under her brush with a hallucinogenic intensity.

At just 22, Maillard is already claiming a visual language so potent, so steeped in the great tumult of history, that it seems impossible she hasn’t been here before. Perhaps, in some reincarnated form, she has.

Born in Sofia, Bulgaria, in 2002, Maillard’s early life wove her between the old world and the new—Sofia to Geneva, East to West, Orthodox icons to Greco-Roman muses, a collision of culture that left its fingerprints all over her work. She is both a historian and a revisionist, pulling from the vast treasure chest of art history while bending its narrative arcs to fit her own mythology.

The lineage of her inspiration is rich and unruly—Baroque grandeur, Renaissance sensuality, Symbolist mysticism, the bruised rebellion of Expressionism. But make no mistake: Maillard isn’t here to play historian. She is here to disrupt, to reclaim, to transmute.

At the core of her work is the body—raw, aching, beautiful, grotesque. It is the battlefield of history and desire, the canvas upon which centuries of power, faith, and oppression have been scrawled in blood and gold leaf. Maillard does not shy away from this inheritance. She embraces it, interrogates it, twists it to her will. Her female figures—part goddess, part ghost, part fleshy, wounded being—step out of their gilded frames and stare us down.

She asks, with an almost dangerous curiosity: why depict the body today, and more importantly, how? It is a question that has haunted the great artists of every era, and yet, in Maillard’s hands, it feels freshly urgent. She paints not just flesh, but the feeling of inhabiting it—the exquisite weight of being alive in a form that has been venerated and vilified, worshiped and wounded.

Her figures possess the reckless sensuality of Klimt’s gilded femmes, the theatrical chiaroscuro of Caravaggio, the bruised vulnerability of Egon Schiele—but with a gaze that is entirely their own. They are not muses, not playthings, not the passive subjects of a male-dominated canon. They are something else entirely: creators, destroyers, witches conjuring their own divinity.

There is also an unmistakable violence in her work—not in the gory, gratuitous sense, but in the way history itself has scarred the female form. The specters of trauma and beauty twine together in her compositions, a dance of agony and ecstasy that is as timeless as art itself. And yet, within this intensity, there is also an undercurrent of tenderness—a knowing softness that refuses to let pain have the last word. Vulnerability, in Maillard’s hands, becomes its own form of rebellion.

Her process, much like her subject matter, is steeped in duality. Classical meets contemporary, oil meets metal, sculpture merges with painting. These aren’t simply figurative works—they are relics of a past she is constantly reinventing, a dialogue between centuries spoken in a language only she seems to understand.

And then, there is beauty. That elusive, intoxicating, perilous concept. Maillard does not trust it—how could she? Art and beauty have always had an obsessive, toxic relationship, one that has so often been wielded against women rather than for them. But she does not abandon it, either. Instead, she reclaims it. She understands that beauty, like power, is a weapon—and in the right hands, it can be turned against its former oppressors.

So here she stands, paint-stained and defiant, a young artist who looks not forward but backward—so far backward that she crashes into the future. Dara Maillard does not simply paint history; she wrestles it to the ground, strips it of its sanctimony, and redresses it in her own vision. If the past is a haunted house, she is the ghost whisperer, summoning the women who have been silenced, erasing their chains, and painting them back into the world on their own terms.

In a world cluttered with fleeting trends and artistic shortcuts, Maillard’s work is a testament to something older, something deeper, something sacred. And if this is only the beginning of her journey, then God help us all—because art history is about to be rewritten.

Read More: https://www.amny.com/new-york/manhattan/the-villager/