Studio 54 in Midtown Manhattan was only open for less than three years, but its iconic legacy has lived on to this day, in its cultural influence and as a place for people of all backgrounds to express themselves. These ideas and the club’s history are showcased in an exhibition opening March 13 at the Brooklyn Museum, called “Studio 54: Night Magic.”

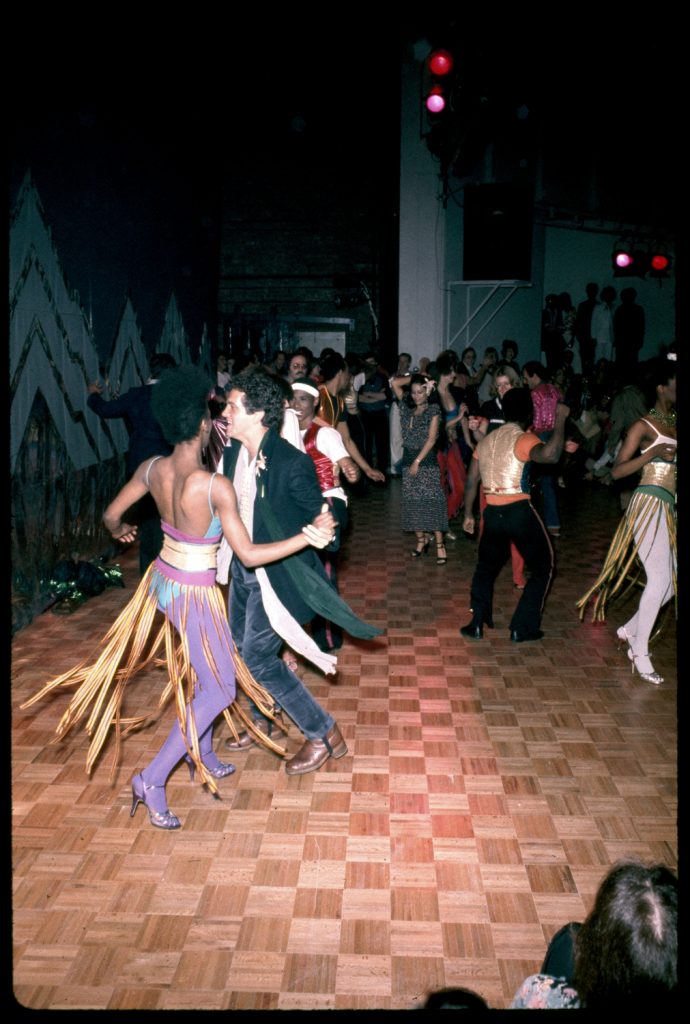

Disco music blares at the exhibition, parts of which recreate the design of the club, which was open from April 26, 1977 to Feb. 2, 1980.

Visitors are taken through the club’s history in chronological order, starting before its birth, with some history of New York City clubs, including the Cotton Club in Harlem, the Peppermint Lounge in Midtown and the West Village’s Café Society (1938-48), which was the first truly integrated nightclub in New York, the exhibition notes, with no seating designations.

New York City’s history during the 1970s is also explored for context. The city was in economic trouble, many neighborhoods were in bad shape and crime was a big problem, the exhibition notes. The 1970s were also a time of political unrest, with Nixon resigning, an oil embargo, and also ongoing movements for the rights of minority and marginalized groups.

The New York City blackout happened months after Studio 54 opened, in July 1977, and shortly after, the “I Heart NY” campaign began. “New York was beginning to rebrand,” the exhibition notes, “and Studio 54 brought the spotlight back to Gotham’s glamour and creative energy.”

The club was owned by Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager, who worked with a team to design the club space, which had previously been an opera house. This included making the stage a dance floor and using kinetic lighting to create the right feel.

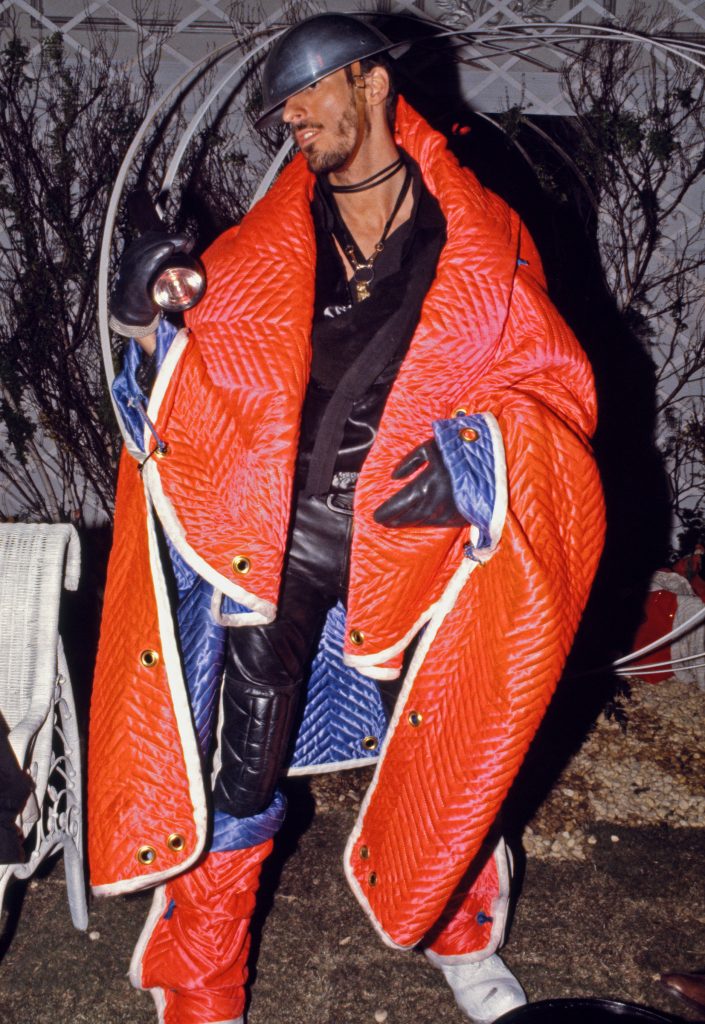

The show includes early architectural plans for the club, and plenty of artifacts from its party days like dresses and other outfits, from glamorous to bold, and party invitations, drink tickets and plenty of photos of dancers and all the famous people who were part of the scene.

“Studio 54 has come to represent the visual height of disco-era America: glamorous people in glamorous fashions, surrounded by gleaming lights and glitter, dancing ‘The Hustle’ in an opera house,” said Matthew Yokobosky, the show’s curator and designer. “At a time of economic crisis, Studio 54 helped New York City to rebrand its image, and set the new gold standard for a dynamic night out. Today the nightclub continues to be a model for social revolution, gender fluidity, and sexual freedom.”

The club’s impact on art is explored in other ways, including appearances in movies and influence on music, such as the hit song “Le Freak” based on the band Chic denied entry to a New Year’s Eve party, and Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive” becoming a classic hit after its popularity with the club’s DJ Richie Kaczor.

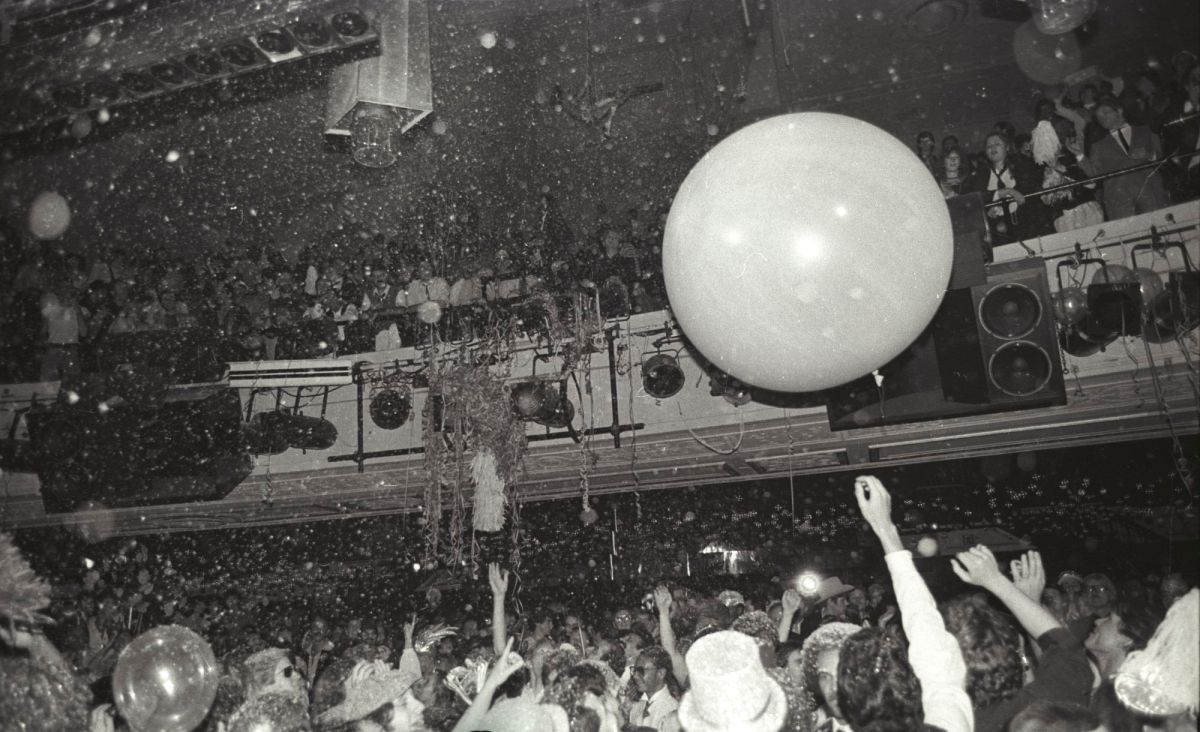

And of course there was the drugs, mentioned in the show such as when several times nightly, images of a moon and spoon would come together in the club and a line of lights would go up the moon’s nose, a not-so-subtle reference to the era’s cocaine use.

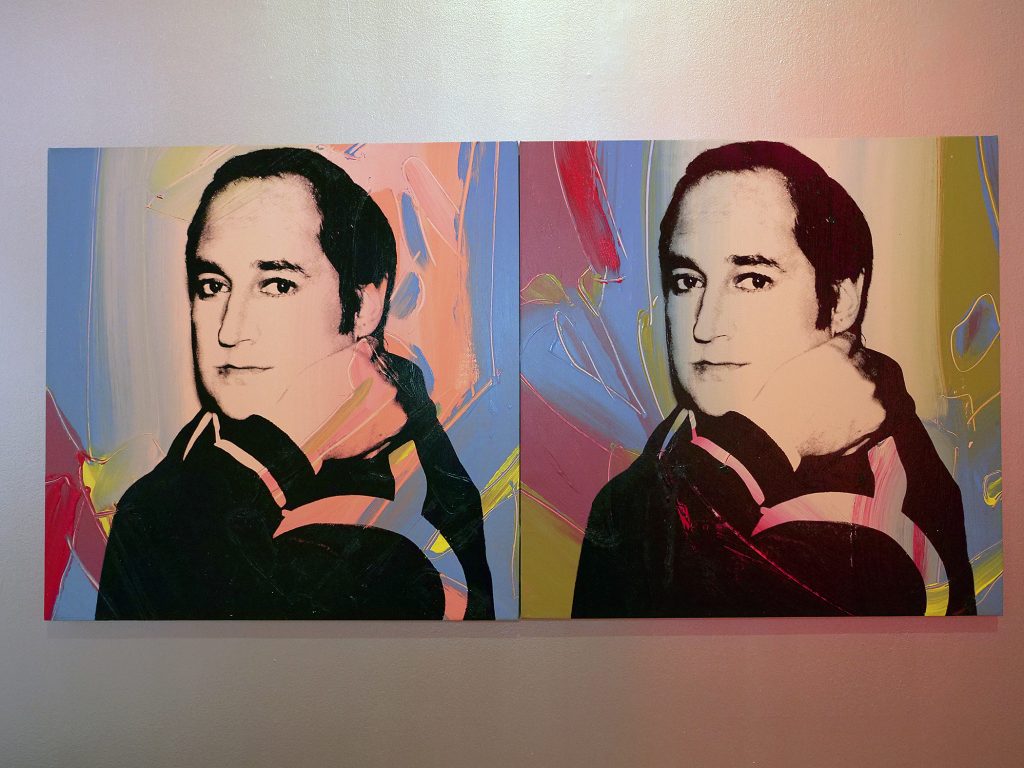

Studio 54 also impacted art, including through Andy Warhol, one of the most famous patrons, who made several works influenced by the club that are included in the exhibition. These include repeating images of drink tickets, and of Neil Sedaka, who would go with Warhol to the club along with other celebrities.

At the exhibition’s entrance, a succinct quote reads, “It was night and suddenly I felt like dancing,” taken from lyrics to “Fashion Pack (Studio 54),” 1978, by Anthony Monn and Amanda Lear.

One of the galleries includes a wall with an extensive listing of parties and special events at Studio 54, including New Year’s Eve parties, fashion shows, birthday parties for Stevie Wonder, Elizabeth Taylor and Bianca Jagger, and of course so much more. All of the parties fit within three years at the club which had an outsized cultural impact that continues on decades later.

The exhibition runs until July 5.