“Vida Americana,” an exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art opening Feb. 17, sheds light on the often-neglected influence that Mexican artists had in the earlier part of the 20th century on their American counterparts to explore social issues, injustices and new styles of painting.

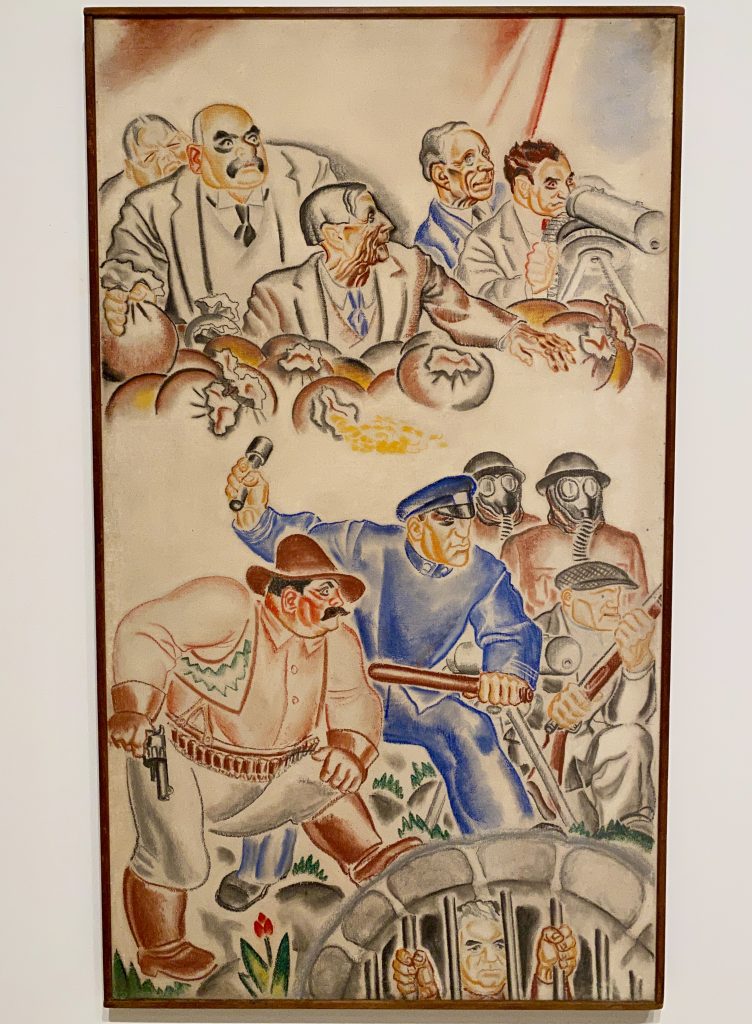

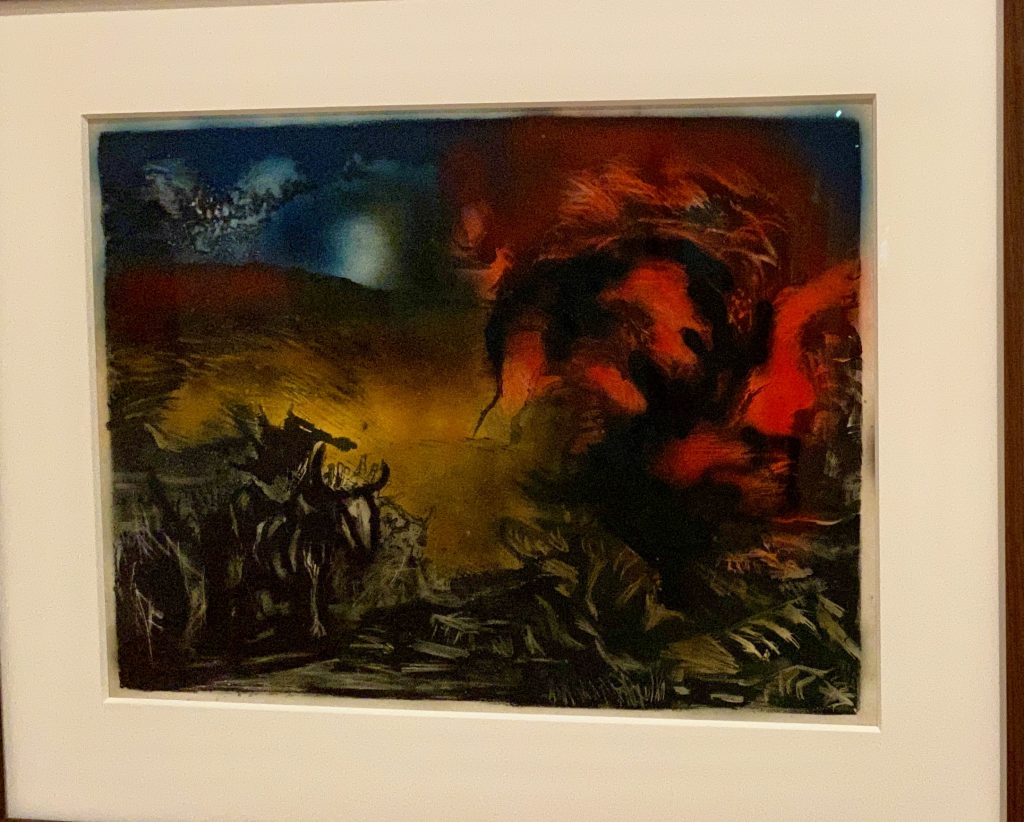

The show notes a cultural renaissance in Mexico at the end of the Mexican Revolution in 1920, including large public murals commissioned by the new government to unify the country, educate about Mexico’s history and show the ideals of the populist revolution.

The murals made art easily accessible for the people, the exhibition notes, and mixed traditions of Indigenous peoples in Mexico with influences from European art.

Many American artists went to Mexico to see the art and work with the artists. Fewer artworks were commissioned in Mexico starting in the mid-1920s under new government leadership, and the top artists, including Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros, traveled to the U.S. to show their works and create new art.

The exhibition focuses on the impact of Mexican artists on those in America from 1925-1945, inspiring American artists to explore themes of America’s history along with issues including labor disputes, unemployment during the Great Depression, and racial violence and inequality.

The show “provides the Whitney an unprecedented opportunity to present a new understanding of art history,” said Adam Weinberg, director of the Whitney Museum, at a preview of the show. “It reminds us that the power of art, and cultural and artistic influences, is not bound by borders.”

Art history has traditionally said that much American art in the 20th century was dominated by French influences, noted curator Barbara Haskell. “This exhibition really rewrites that narrative,” she said.

The show was 15 years in the making, going back to when Haskell looked at art of the Mexican revolution, she said, and noticed similarities in the work of Rivera and Thomas Hart Benton. She found influences on American artists stylistically but also in substance, depicting fights against oppression and for justice, she noted, and the concept of art being for everyone, “in a style that’s accessible to the public,” Haskell said.

The show features works of American and Mexican artists, and reproductions of large public murals. Depictions of uprisings and revolutions in Mexico are contrasted with labor disputes in America and discrimination faced by African Americans who migrated north, along with the history of African Americans and struggles for equality.

A section of the show details Diego Rivera’s 1932 artistic commission at Rockefeller Center, which led to controversy when Rivera refused to remove a portrait of Vladimir Lenin and was dismissed from the project in 1933.

There was also some bitterness among American artists for Rivera getting the commission when employment was scarce during the Great Depression. This led to an exhibit organized at the Museum of Modern Art for American artists, which also drew controversy when the museum objected to communist themes from several artists. But artists protested and the museum allowed the works to stay in the face of potentially bad public relations.

Style influences are also explored in the show. In 1936, Siqueiros established the Experimental Workshop near Union Square in New York, as way to explore new artistic techniques.

Jackson Pollock was among the artists who joined the Workshop when it first opened, and was especially taken with Siqueiros using unconventional materials and ways of applying paint, the exhibition notes. This included spraying paint through stencils and dripping, pouring, splattering and throwing paint at the canvas, which would stick with Pollock as he developed his drip paintings. “Each age finds its own technique,” Pollock would say, a similar idea to what Siqueiros founded his Experimental Workshop on.

“Vida Americana” will run at the Whitney Museum, 99 Gansevoort St., from Feb. 17 to May 17.