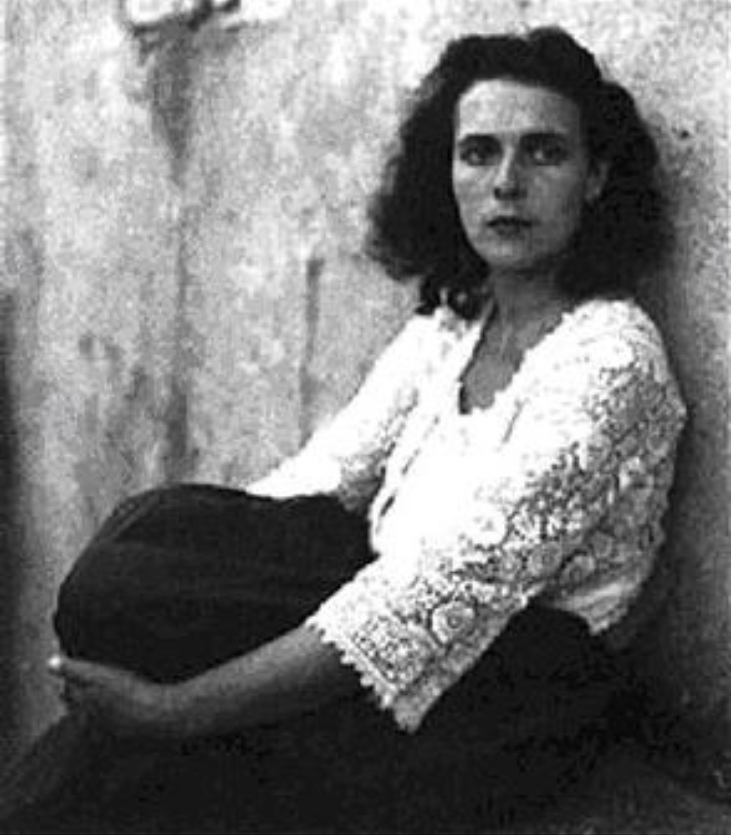

Leonora Carrington wasn’t merely an artist — she was a shaman, a mythmaker, a feral intellect who refused to bend to the crushing banalities of the world.

Her art doesn’t simply invite you in; it dismantles your assumptions, dissects your certainties, and reconstructs them into something terrifying and transcendent. To engage with Carrington is to engage with the primal and the profound, the feminine and the ferocious.

Born into the suffocating privilege of Edwardian England, Carrington was a debutante whose rebellion was less a phase and more a philosophical stance. By the time she was expelled from her third convent school, it was clear: Carrington wasn’t just rejecting the institutions of her time—she was rejecting the very fabric of its patriarchal narratives.

The daughter of industrial wealth, she was destined for society luncheons and dynastic marriages, but Carrington opted instead for Paris, Surrealism, and liberation.

Her initiation into the Surrealist circle could have rendered her a muse — objectified and mythologized by men whose visions often eclipsed their subjects. But Carrington, fiercely intellectual and intuitively radical, shattered that dynamic. She was not a satellite orbiting male genius but a celestial force of her own. She wielded the lexicon of Surrealism—dream logic, symbolic alchemy, the collapse of binaries—not as a borrowed language but as her birthright.

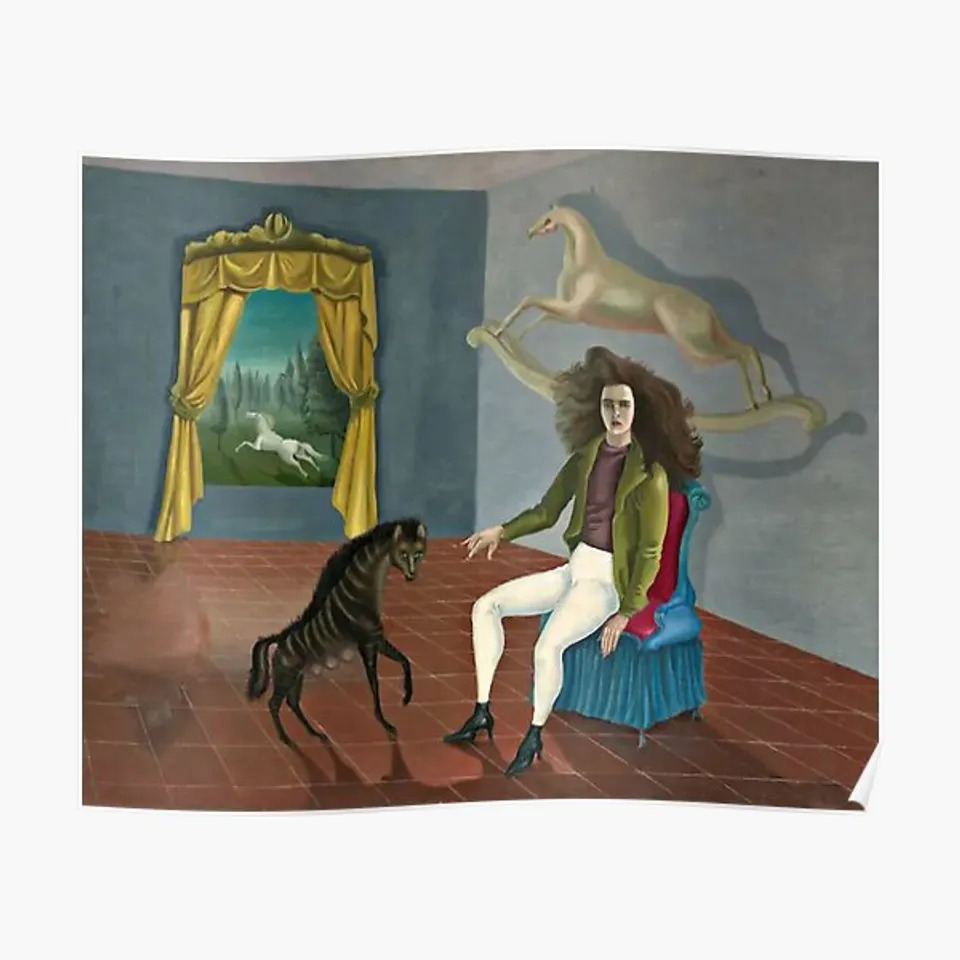

Her work is unlike anything else in the canon of modern art. Carrington’s paintings are at once intimate and cosmic, cerebral and visceral. In “The Giantess (The Guardian of the Egg)”, a towering maternal figure cradles an egg, her expression serene yet commanding. This is not the sentimental motherhood of Western art; it is archetypal creation, the fragile yet infinite potential of life.

The egg, as both symbol and form, contains multitudes—fertility, fragility, transformation. It’s a theme that runs throughout her oeuvre: the liminal space where opposites meet, collide, and dissolve.

Carrington’s canvases teem with chimeric figures, their bodies merging with animals, vegetation, and the cosmos. Her women are witches and warriors, avatars of a feminine power that transcends the human. Her vision was deeply informed by esoteric traditions—alchemy, Kabbalah, Celtic mythologies—and by a profound reverence for the subconscious as a source of truth. But unlike many of her Surrealist peers, Carrington’s exploration of the unconscious was not solipsistic. It was ecological, interconnected, and profoundly feminist.

Carrington’s life itself was a tapestry of myth and intellect. During the World War II, her lover Max Ernst was arrested by the Nazis, triggering a psychotic break that led to her institutionalization in Spain. Her escape was as harrowing as it was cinematic: sedated, imprisoned, exorcised of her agency, Carrington emerged from the ordeal more unyielding than ever.

Mexico became her sanctuary, a place where she not only survived but flourished. There, she forged deep connections with artists like Remedios Varo and Frida Kahlo, engaging in a creative and intellectual exchange that transformed her work.

Her later years saw her embrace writing with the same ferocity she brought to painting. In The Hearing Trumpet, Carrington crafts a narrative as surreal as her canvases—an anarchic meditation on aging, freedom, and the absurd. It is a text that defies categorization, much like its author, blending feminist critique with esoteric humor in a way that feels timelessly subversive.

What makes Carrington so compelling, so necessary, is that she transcends the frameworks we use to contain artists. She is not simply a Surrealist, a feminist, or even a painter. She is an alchemist, transforming the detritus of human experience into something sacred. Her work does not seek to explain; it seeks to evoke, to provoke, to awaken. Carrington understood that art is not a mirror—it is a portal.

Leonora Carrington’s legacy is a challenge. It is a call to reclaim the mysteries of the feminine, to engage with the unconscious not as a dark void but as a fertile terrain. To view her work is to step into that terrain, to allow yourself to be remade by its revelations. The question isn’t whether Carrington’s art is relevant—it’s whether we, in our sanitized, over-rationalized modernity, are brave enough to meet it on its terms.

She was the woman who refused to be contained, the artist who rejected the binaries of her time, and the visionary who dared to paint what others could not even articulate. She was, and remains, untamable.

Read More: https://www.amny.com/new-york/manhattan/the-villager/