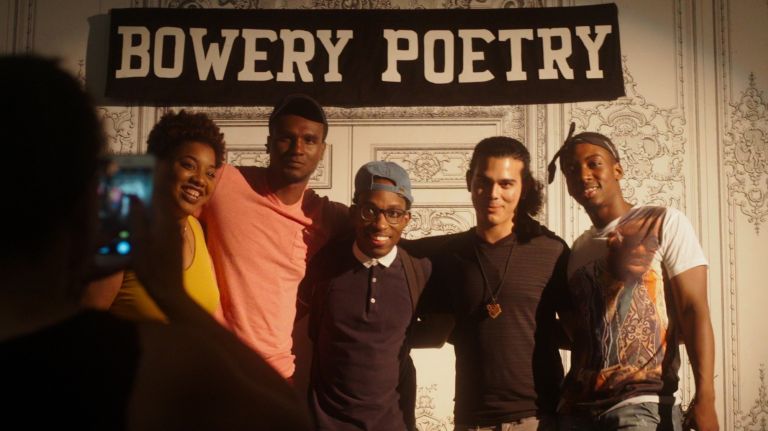

Being vulnerable for the sake of authenticity is the driving force pushing slam poets forward in first-time director Max Powers’ documentary “Don’t Be Nice.” Powers uses the verité style of filmmaking — a documentary technique that allows the subject to be captured in an honest way so audiences feel they’re observing a truthful depiction — to capture a troop of five poets of color (Timothy DuWhite, Noel Quiñones, Joel Francois, Ashley August and Sean "Mega" DesVignes) from the Bowery Slam Poetry team as they prepare for nationals.

To dismantle the performative criteria that slam is known for, coach Lauren Whitehead encourages the poets to dig deep into their discomfort, emphasizing that using their vulnerability is a powerful use of freedom of expression. The urgency behind the troop’s triumph, both individually and as a whole, is captured during the summer of 2016 when there’s a swell of media coverage around police brutality affecting black and brown lives. The film uses the backdrop of racial tensions and the Black Lives Matter movement as it follows this particular troop.

amNewYork spoke with Powers about his first film, opening at the IFC Center on Friday.

Editors Note: The following has been edited and condensed from two interviews.

There are these little hidden communities of artists in New York but a lot of it has gone digital. The film really focuses on that small tight-knit community in New York. It’s easy to forget that these spaces really do exist.

Especially with how the communities in New York are changing so rapidly. Especially with everything going on in digital like you said. No matter how many Whole Foods and John Varvatos stores pop up on the Bowery, there’s still these pockets of culture that continue to persist even through the change. I hope that people [who] watch the film will seek [slam poetry venues] out.

What do you think it is about New York that lends itself to this art form?

I think that it’s a unique art form for many reasons. One of the reasons is because it is scored and has a competitive element. I think it lends itself to a really dense urban environment because you can really have that sense of competition, which for this art form really just fosters and facilitates an intense creativity. I think that once something is scored it definitely kind of turns up the heat and puts on the pressure to really make that work.

You covered a time where many see this as the height of Black Lives Matter movement. Was that a conscious decision on your part?

One of the special and difficult things about making a verité film is you really don’t know what’s going to happen. You’re filming a lot of discussions and a lot of open-ended interviews, and we didn’t go into it saying, for the first third of the movie, we’re gonna talk about the political dynamics in the Black Lives Matter movement. Then in the edit it was about seeing what the patterns were. What were the interesting conversations? And where the poets and the coaches were taking the work themselves. The events during that summer did coincide with the poetry that the poets were writing, but there wasn’t a preconceived direction … it just kind of happened in front of us.

We’re seeing these artists at a very specific time in their lives through a season of violence that was documented by the media in a new way. By using this art form to speak to the violence of that summer, did it give you a new perspective of that time?

I think it did. I think the violence of that summer did give me a unique perspective, but … I think those events and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement seem to define that summer in a lot of people’s heads. The thing is that those events have always been happening and are continuing to happen. A lot of the poets work and the themes that were being discussed around police violence — those weren’t new to that summer. They just happened to be heightened in the cultural consciousness. I think that’s why the film is so important now because people can watch it and remember that they were paying attention to these events that summer, even though these events continue to happen.

The film opens up a conversation about the importance of personalizing art and how it’s a careful balance of being vulnerable versus exploitative. There was a moment when one of the artists opens up about being sexually assaulted and how by participating in the poem "The Purge" it re-traumatized him in a way he wasn’t ready for. What were you thinking after that moment?

We had been with the team filming for a really long time at that point. When you’re filming with a group of people for many months, you kind of feel part of the same group. If anyone ever during the process told us to turn off the camera, then we’d turn off the camera. When Tim was going through that emotional moment he was aware that we were filming. So, after that happened, half of me was like, wow, that was a really emotional moment that we captured on camera. I was also saying to myself, holy s—, this is really hard for Tim and I really hope that he’s going to be OK. Following people for a really long time you do have a bit of a split consciousness between wanting to do your best for the film and paying attention to that and also being close to your subjects and to the team. It’s a complicated feeling after a scene like that.

How did you balance that line yourself between documenting vulnerability to service the film without allowing exploitation to happen?

I think that you just have to kind of go with your gut in the moment and feel out if something is becoming too much. There were points in this film where the cinematographer and I would look at each other from across the room and silently communicate that we’re gonna take a little break. You just kind of feel that moment to moment and hope that you get that right. You can push people to a point where they really don’t want to be filmed anymore. And we didn’t have much of that on this film.

A New York Times article last year detailed issues the poets in the documentary had with the film. What was your reaction when you found out the poets felt exploited?

I was disappointed. It’s tough to pour your heart and soul into a film and have someone who has a different opinion about a part of that film. I don’t want to speak for the poets in any way, but of course I was disappointed. One of the things that we did with this film that I’m very proud of is, most documentaries, follow one, two, three subjects and in this documentary, we really wanted to make it an ensemble piece. I wanted to make sure that we highlighted each poet and their work. When you do that and you are now up to five, six, seven subjects, including the coaches, you’ve gotta make some really hard decisions. As with any documentary, everyone’s gonna have a point of view about things that they may feel should have been done better or differently. [Having said that], I really stand behind the film.

Given that this is your first film, what do you think you’ve learned from the experience of post production, all the way through to the poets’ reaction to the film?

I think I’ve learned that all the decisions that go into making a documentary are difficult. I think that you do your absolute best to scrutinize your decisions and make the best film that you possibly can. I guess I’d say I’m still learning. I think that as the first film, I really stand behind it and feel that the entire team from beginning with the poets and their incredible work to our producing team, to our editors and our cinematographer, we all did the best job that we possibly could have. I think … [long pause] I guess I would say that you always have to keep trying to make the best film that you possibly can and that’s what I’m going to do with the next one.