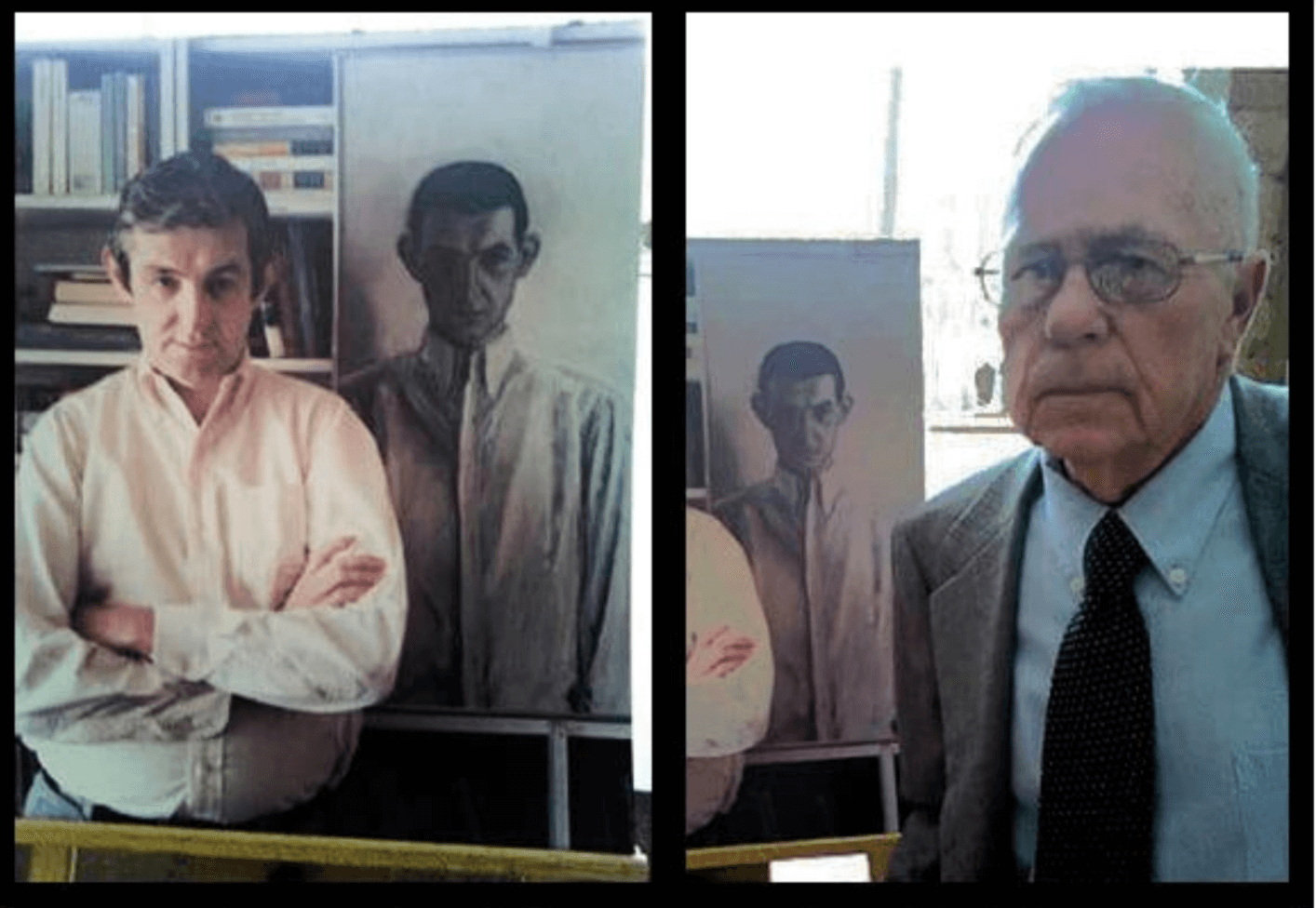

For more than 50 years, John Norwood had created art out of recycled materials in his College Point home. Norwood, who was an artist, sculptor and model maker, wanted to be a living national treasure, according to his wife, Dr. Ruby Malva.

“He wanted someone to look at his art and buy it. He wanted it to go into the museums, but somehow it never clicked,” Malva said. “He must’ve sent out about 100 copies of his artwork to about 100 museums and art magazines.”

Norwood, who was known for turning trash into treasure, died on March 6 at the age of 84. He is survived by his wife, whom he was married to for 47 years, his two daughters Daniella and Erica, and two grandchildren.

According to Malva, Norwood kept on producing artwork — paintings, drawings, foam sculptures, and various mixed media pieces of art from recycled materials — in his studio up until the very end.

“Being with him, I know a lot about artists and about artwork. John loved his art — he had a certain taste,” Malva said. “He never let me throw away everything. He used to take my plastic containers and made things out of them, and he used foam and cardboard and created art with that.”

Norwood recycled everything that came into his environment — whether it was vaccine boxes that he stacked and painted red, yellow and white, or Marlboro cigarette packs, cigarette butts, matches, spray cans, coffee cups and cardboard of any kind.

“I think the waste in our society is fantastic and when it comes into my environment, I have to do something with it,” Norwood said in his contemporary artist bio on YouTube.

Norwood was born on Jan. 25, 1937 in Durham, N.C., and moved to Norfolk, Va., when he was 5 years old. He attended The College of William and Mary (now Old Dominion University) for two years and then received the Out of State Fellowship from Virginia Museum of Fine Arts to study art in 1957. He used this fellowship to attend the Art Institute of Chicago for two years.

After spending some time in Europe, where he studied art history, music and theatre in several different countries, Norwood returned to New York City and got a job in New Jersey making architectural models. He then moved to Manhattan and started working with I.M. Pei’s model shop and soon after met his wife, Ruby at a Halloween party in 1970.

Norwood and Malva were married in 1972 and had two daughters, Daniella and Erica. The couple moved to College Point in 1974, as Malva started her pediatrician practice and opened an office in the community the following year.

“I always used to say I’m a type A and he’s a type Z because I’m always a very hyper person wanting to get things done, but John had a laid back personality,” Malva said. “He was very kind and also quiet, staying at home. He was very good with the children. While I was working, he used to do homework with the kids and did a lot for them.”

Norwood had renovated their home that sits on College Point’s waterfront with a view of Manhattan and a glorious sunset. However, one day Norwood ended up losing a large percentage of his artwork after a devastating fire broke out in their home, according to Malva, who recalled the incident that occurred 10 years ago.

“It was a cold day and John had heaters plugged into three plugs that caught on fire,” Malva said. “The fire was downstairs and all of his artwork — pieces that he had worked on for three to six months — was lost. It was traumatic because his plexiglass pieces that were in the Queens Museum went with that too.”

However, it didn’t stop Norwood from creating, according to Malva. After rebuilding their home, Norwood continued to paint and worked with glue and foam creating collages. Eventually, their home was filled with an additional few hundred paintings and sculptures of all shapes and sizes.

“He never wanted to leave his home in College Point. He said ‘this is my place and am going to die here,’” Malva said.

Norwood’s home has been converted into a museum/gallery that contains his life’s work, that is known as the Norwood Museum. The College Point site has received a rating of five stars on TripAdvisor, and according to Malva, they’ve had about 200 to 300 visitors. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s been closed.

Norwood’s work has been featured at the Jamaica Center for Arts and Learning, Queens Theatre in the Park in Flushing and the Queens Museum of Art, among other sites. He has also been featured in interviews about his artwork on CBS News, NY 1 and Queens Public Television.

“John told me he was a ‘living national treasure’ at least a thousand times over the past 42 years, all with a sly smile on his face and always ready to launch into a barrage of politically incorrect off-color jokes that were funny as hell despite having heard each and every one a thousand times as well,” said Bellinger, who was offered an alley studio space in a building the Norwood’s owned in College Point.

According to Bellinger, Norwood would stop by the studio and invite him and others to his own enormous studio space in the adjoining building.

“John would call me every week or so throughout this pandemic or leave a message that usually began, ‘Hi Len, it’s god, just called to chat, nothing important, give me a call back’ followed by a slightly southern drawled, ‘it’s not really god, it’s John, bye!’” Bellinger said.

According to Malva, Norwood had lived a good life traveling with his family to different countries.

“We traveled a lot — we took 40 cruises and I never went away without him or him without me,” Malva said. “On most of our vacations we never thought about work. We loved Machu Picchu and the Galapagos, and he loved Japan, he liked simple things.”

Norwood’s work has been featured at the Jamaica Center for Arts and Learning, Queens Theatre in the Park in Flushing and the Queens Museum of Art, among other sites. He has also been featured in interviews about his artwork on CBS News, NY 1 and Queens Public Television.

This article first appeared on our sister site, www,qns.com