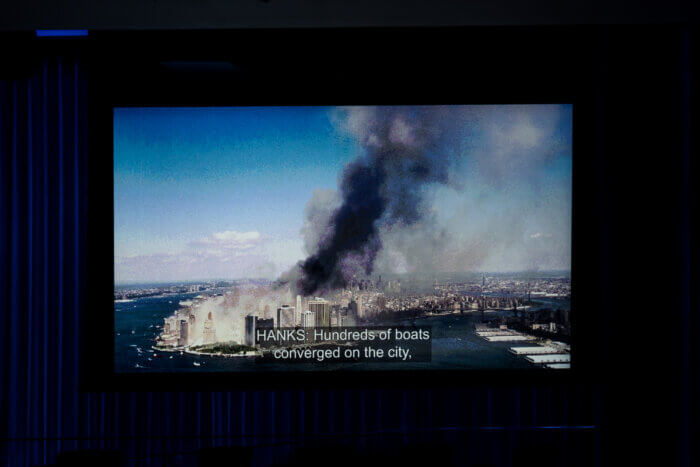

As terrorists brought down the World Trade Center on 9/11, marking the worst terror attack in U.S. history, it became increasingly difficult to evacuate Lower Manhattan. Thousands ran south to the water’s edge, trying to escape the raging inferno, only to realize they were stranded on the island with no way out because the tunnels were closed and subway service halted.

Spontaneously, a fleet of around 150 maritime vessels, including passenger ferries, tugboats, merchant ships, private vessels, and New York City Fire Department and Police Department boats, jumped into action and rescued between 300,000 to 500,000 people from the disaster zone in Lower Manhattan, taking them to New Jersey and Brooklyn.

On Oct. 23, the 9/11 Memorial & Museum hosted a screening of “Boatlift,” an award-winning short documentary narrated by Tom Hanks, which tells the untold and heroic story of the largest maritime rescue in country’s history and the firsthand accounts of boat captains and passengers.

The U.S. Coast Guard coordinated the rescue, and the short film reminds of the selfless acts of New Yorkers who jumped into action, saving many lives.

Following the screening, Noah Rauch, senior vice president of Education & Public programs of the 9/11 Memorial & Museum, led a conversation with the film’s director, Eddie Rosenstein, U.S. Coast Guard Safety & Security Division Chief John Hillin, former FDNY Chief Marine Engineer Gulmar Parga, and NY Waterway Captain Richard Thornton, reflecting on the massive, improvised yet orderly evacuation.

Accomplished Emmy-nominated filmmaker Rosenstein produced “Boatlift” in commemoration of the 10th anniversary of 9/11 and described the attacks and what followed as America’s finest example of people coming together in tragic moments.

“The people in my company, including Rick, went and met dozens of captains to see if this is actually real and to put them on tape and see if we can pick a bunch that might be able to represent the story,” Rosenstein said. “We weren’t even sure how to tell the story. And as I watched the interviews, preliminary stuff, the story became pretty clear.”

On 9/11, NY Waterway Captain Thornton operated the ferry between Port Imperial in Weehawken and Manhattan. During the pre-dawn days of iPhones, passengers told him they had heard on the radio that a plane had hit the North Tower of the World Trade Center.

At first, Thornton assumed it was a small plane. Even when he realized it was a passenger plane, he thought it was a tragic accident until he and his crew saw the second plane hit the South Tower.

He acted immediately, without even notifying the company’s management, and raced to the scene. Upon approaching Lower Manhattan, Thornton and his crew saw people jumping out of the towers, desperately attempting to escape the fiery hell.

“It was very nearly overwhelming emotionally to see that because some of those people we bring to work on the ferry,” Thornton said. “We also saw people massing along the waterfront, along the seawall, and some of them were just in panic. People are jumping into the water, swimming out of Manhattan, and all of our ferries are racing to the scene at 20 or 30 knots.”

Thornton said that when the South Tower collapsed, everyone went “dead silent,” realizing that thousands of people had just died.

There was zero visibility because of the plume of smoke, ash and dust, yet the vessels heading to Lower Manhattan didn’t collide.

“The rules get thrown out the window, and then you adapt,” U.S. Coast Guard Chief Hillin said. “I don’t think that the vessels not colliding was luck. These people are used to operating in tight quarters around all different types of vessels.”

FDNY Chief Marine Engineer Gulmar Parga and his unit rushed out once the first plane hit the World Trade Center. Parga recalled a “waterfall of people” falling onto the boats after the first tower collapsed.

Once the dust cloud had cleared, the FDNY took about 250 people, including six infants, across the river to New Jersey to an abandoned pier, where first responders from Hoboken helped FDNY firefighters get the injured off the boat.

The FDNY marine boat returned to Manhattan and was tasked with pumping water from the river because all the fire mains west of the World Trade Center had ruptured.

“But after that, we were still helping,” Parga said. “There [were] civilians crossing our boat to get to other boats that were tied up outside us that were still evacuating all those civilians. It’s an honor to have participated in what we did.”

Retired Battalion Fire Chief Joe Parkin Jr. attended the screening with his son Christoper and his brother, Firefighter Capt. Scott Parkin. Parkin and fellow firefighters from Patterson, New Jersey, aided in the firefighting operations for 38 hours, working alongside Parga and his fireboat crew.

While it was his first time seeing the documentary, he was already well versed in the massive maritime rescue mission.

“We were brought over by a New York City Harbor Patrol Boat that day,” Parkin recalled. “And in the course of our travels across from Liberty State Park to the South Cove, I noticed boats streaming from all different directions and moving about during the course of the day evacuating people.”

Parkin said Rosenstein did a great job with the documentary. “It brought back some memories [of] that day for sure.”

His brother Scott was also part of the rescue and recovery mission. The boatlift was already in full swing when he arrived through the Holland Tunnel to work on the pile and tunneling operations.

Scott Parkin, who described the documentary as “moving,” said that as terrible as the day was, “beams of light” were coming through from different areas, and the boatlift was one of them.

“To see this all these years later, you really, really appreciate how everything just naturally came together,” Scott Parkin said. “Divine intervention or whatever you want to call it, that you could have that amount of cooperation from so many different people and all strangers and nobody’s communicating really. And everybody’s coming in and working and doing their thing, and no catastrophes, no lives lost during that operation, everybody got on amongst a massive amount of chaos.”

The 9/11 Memorial is open daily from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., and the 9/11 Museum is open from Wednesday to Monday from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. Starting Nov. 8, the documentary will be shown at the museum throughout the day.

Read more: Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs Held Without Bail on Trafficking Charges