While most of the science establishing global warming has been around since the ninth Earth Day celebration 40 years ago, wide swaths of the country continue to deny both the science and the fact that humans have any effect on climate change.

It wasn’t always that way.

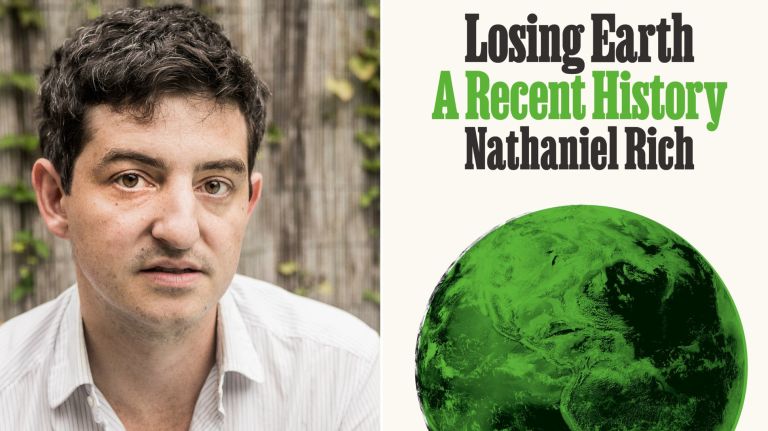

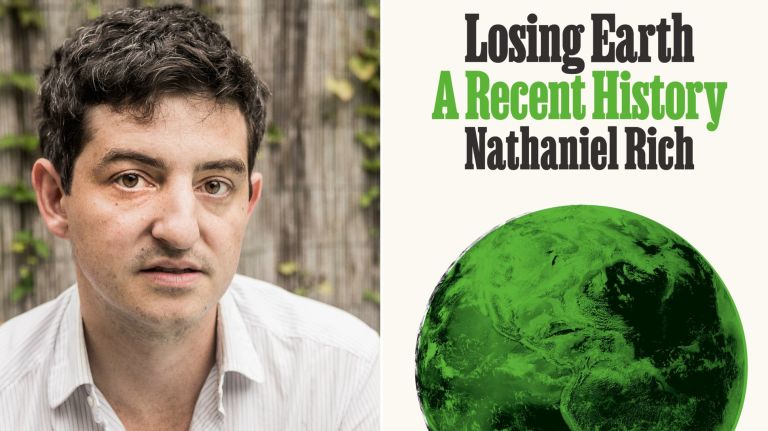

“There is really no conversation that we have about climate change today that wasn’t being held verbatim by 1980,” says Nathaniel Rich, author of “Losing Earth.”

The book, out this month, is based on his August 2018 New York Times Magazine article, written in partnership with the Pulitzer Center, that details the moment in the 1980s when “we came so close, as a civilization, to breaking our suicide pact with fossil fuels.”

At the end of that decade, Rich says, “the oil and gas industry gets involved in a coordinated way, starts this multi-decade propaganda machine, starts buying off scientists and politicians and ultimately an entire political party, in order to thwart any kind of climate policy.”

Rich spoke with amNewYork about the article, the frustrations of the present and the hope for the future.

What was the response to the article?

The response was staggering, at a global level. … I spent the next three weeks doing almost nonstop interviews. … There was just an enormous outpouring of interest and excitement and despair and anger and every possible emotional response. … I spent a couple months going around the country speaking at middle schools and high schools and university programs … being asked … what do we make of this history, what lessons should we draw from it and how does this change the way we go forward? … [The book] gave me the opportunity to write a new essay to serve as a new afterword to respond to some of those questions [as well as add a few chapters].

The Republican Party comes in for some blunt criticism in that afterword.

We are in this remarkable fantasy realm where the Republican Party now is further into the swamp of denialism than the oil and gas industry in its own public statements. … I’m not saying that [oil companies] are actually acting virtuously, but at least in their public relations they understand that it’s no longer tenable to go out in public and pretend that science is made up. … The first thing is to point out the absurdity of it, and the childishness of it. … The second is that it’s certainly connected to a lot of other things going on in that party intellectually, of questioning objective fact. … But I think you have to question whether this Trump Republican Party is built for the long run.

Sounds like the younger generation is filling that leadership vacuum.

I think there is a huge opportunity, and I think you see a younger generation understanding that. … They are leading already, they’re pushing the conversation already, and of course the stakes are clear to them because their lives are more greatly affected. When you really look at the stakes … you realize that this is not only a political crisis but a moral crisis, and that dictates a different kind of argument. And they’re making it.

Do you remain optimistic?

It’s inevitably the question … and it’s based on a faulty premise, which is that there is salvation or defeat, when of course there’s a huge range of outcomes in between. I think best-case scenario is not so great, but I also don’t think that we’re destined for the worst-case scenario. … For too long our conversations have been reduced into this childish framework of hope or despair, optimism or pessimism, victory or defeat, and I feel like this is an extraordinarily complicated issue that will require a massive transformation of our society and of our economy and of our politics, and we should be adults about it.