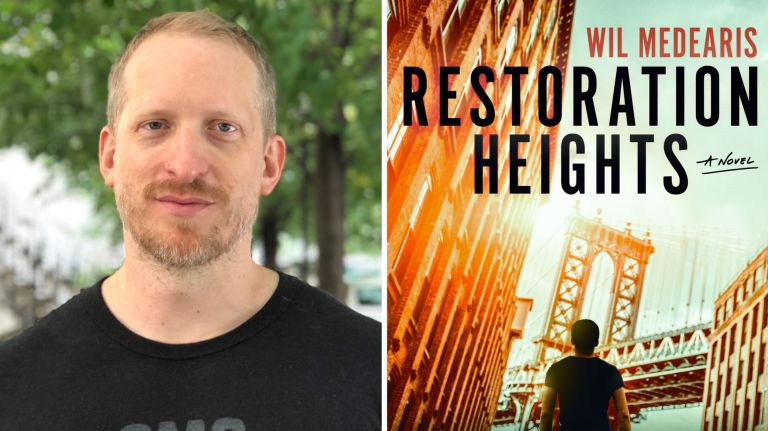

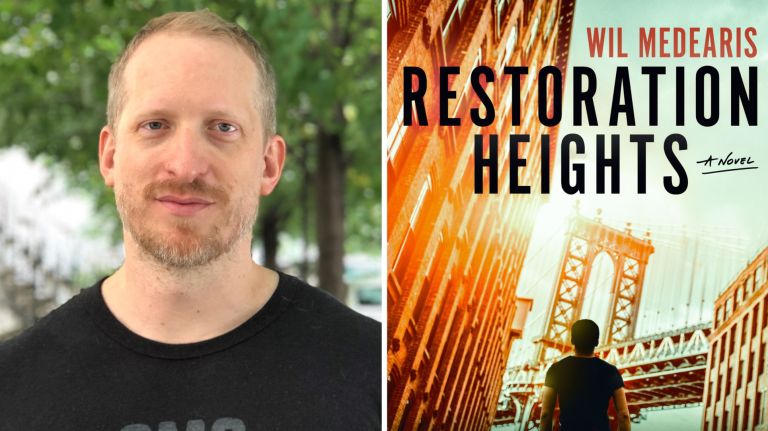

After a career in painting, Brooklyn artist Wil Medearis has switched mediums to pen a mystery.

His debut novel, “Restoration Heights,” out Tuesday, follows art installer Reddick and his quest to find Hannah, a missing woman connected to a wealthy Manhattan family. The tale also explores conversations about gentrification and the effects it has on neighborhoods like Bedford-Stuyvesant, where both Medearis and Reddick live.

amNewYork spoke with the author, 42, about writing a mystery, how art school influenced his craft and what he wants readers to learn from the story.

What made you decide to write a novel?

Growing up, I was kind of always into writing, art, acting — anything in the arts, generally. I ended up going back to school and I was focused more on making art but would still intermittently write some stories. And then at some point shortly after grad school, I was showing [in galleries] in Philadelphia and Virginia, but at the same time I had these ideas for writing. So I really ended up transitioning more toward that after I moved to New York in 2010. I wrote a book before “Restoration Heights” that never made it out of my studio.

Why did you choose to write a mystery?

The easy answer is, I enjoy mysteries. Obviously you write things that you enjoy. I learned lessons from the book that I tried to write before, where I just sort of had maybe gone too big and I thought if I write a mystery, it’s very structured. I thought that would be useful in helping keep the novel and the writing process focused.

Is it smart to go looking for a missing person on your own in New York City?

Probably not, but I guess you have to follow your instincts. It’s a very large city, it’s probably best to let people live their own lives unless they’re in immediate harm’s way. But I will add that one thing about New York: In the South you hear, “those Yanks are so rude,” but then you come here and it’s not like that. People help carry strollers down the subway steps. People do find ways to care about and respond to anyone that’s in distress.

How did you learn to write dialogue and other elements of fiction?

I learned from reading constantly, and reading across genres. If you’re a bookworm you develop a feel for those types of things. And then, in art school, in addition to learning the technical traits for your specific medium, you’re engaging in critical dialogue with students and teachers, so you learn how to have that dialogue. But the thing you need to learn is how to fix it, and that takes patience and practice.

What was the biggest challenge in the process?

I guess the most difficult part was being patient, and that means understanding that you’re going to have bad days. You’re going to have 3,000-word workdays and you’re going to have 300-word days. Coming to grips with that was difficult, because you obviously want every day to be good. You want to kill it every day, but that’s just not at all how writing works.

Why did you choose to set the novel in Bed-Stuy?

I had my own experience of living here. I’m a member of the Bed-Stuy YMCA, which is featured predominantly in the book, and through that I have friends that I wouldn’t otherwise encounter in my day-to-day life.

What did you want to portray about the city today?

People’s different reactions to change. It’s really easy to romanticize a certain time in the city, but it’s constantly changing, so I wanted to have a diverse array of viewpoints. People aren’t unified and their reactions to gentrification are going to vary a lot according to their experiences as an individual, as well as their race or class or age. It hurts people and it also can help some people, and that was important for me to portray.

Brooklyn bedfellows

Here are some of author Wil Medearis’ favorite reads set in Brooklyn:

1: “Manhattan Beach” by Jennifer Egan

2: “The Fortress of Solitude” by Jonathan Lethem

3: “Self-Portrait with Boy” by Rachel Lyon

4: “The Drop” by Dennis Lehane

5: “The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay” by Michael Chabon