‘The Iceman Cometh’ runs through July 1 at Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, 242 W. 45th St., icemanonbroadway.com

According to Eugene O’Neill’s written character descriptions for “The Iceman Cometh,” Theodore Hickman (i.e. Hickey), the big-spending, jovial hardware salesman who lights up Harry Hope’s dingy West Village saloon and cheers up his downtrodden inhabitants, is heavyset, bald, short, round-faced and button-nosed.

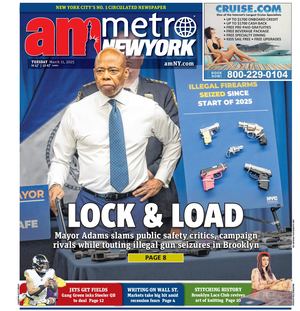

In order words, Hickey (played by Nathan Lane three years ago at BAM) would not appear to be a role destined for Denzel Washington — yet here he is on Broadway giving a first-rate performance in a first-class revival of O’Neill’s titanic 1946 tragedy of shattered dreams, hopelessness and inebriation.

Under the focused direction of George C. Wolfe, the play has been cut down from five to four hours in length — which is not an unwelcome change given that the script is lumbering and repetitious (including its endless “pipe dream” references).

Set in 1912, Harry (Colm Meaney, “Star Trek: Deep Space Nine”) and his customers (many living in ramshackle tenements above the bar) are eagerly anticipating a rare visit from Hickey.

Upon Hickey’s entrance (approximately an hour after the play begins), the gang can sense that something about him is off. In an evangelical and twisted state of mind, Hickey announces that he is now sober and happier, having rid himself of all “pipe dreams.” Not only that, he is determined to make converts out of everyone else. He will force them to leave the bar and reclaim their shattered lives.

Larry Slade (David Morse, “St. Elsewhere”), a political anarchist turned cynic who is essentially a stand-in for O’Neill, becomes suspicious of Hickey’s personality change, which eventually leads to uncomfortable revelations from Hickey about the fate of his wife (who, Hickey likes to joke, regularly cheats on him with the iceman), culminating in a long confessional monologue.

Wolfe is often too self-conscious in his direction, fiddling with the set design (the back wall is missing, the ceiling suddenly materializes, a piano player is unnecessarily added) and blocking (often having the cast fixed in frozen tableaux).

Nevertheless, the production succeeds largely on account of a terrific ensemble (which also includes Frank Wood, Bill Irwin, Michael Potts, Tammy Blanchard and Austin Butler) in great character roles. A clear contrast is made between them and Washington, who is physical, pugnacious and unapologetically unsettling as Hickey.