The solo show, long a fixture of experimental and autobiographical theater, is currently getting a prestige makeover, with two well-known foreign actors each taking on a canonical text from the late 19th century and portraying all of its characters, including Andrew Scott in “Vanya” (adapted from Anton Chekhov’s tragicomedy “Uncle Vanya”) and Sarah Snook in “The Picture of Dorian Gray” (a dramatization of Oscar Wilde’s 1890 gothic thriller novel).

The results, as seen in their high-profile productions, are undeniably ambitious, technically impressive, and often thrilling. But they also reveal the limitations of the form, especially when it comes to clarity and cohesion.

One might have expected “Vanya” to play Broadway following its acclaimed London debut. Instead, it is running at Off-Broadway’s Lucille Lortel Theatre in the West Village, which has recently hosted Aubrey Plaza in “Danny and the Deep Blue Sea,” Adam Driver in “Hold On To Me Darling,” and the pre-Broadway debut of Cole Escola’s “Oh, Mary!” Playing a smaller venue adds to the production’s intimacy and makes it a more exclusive ticket.

Scott, an Irish actor whose screen work includes “Fleabag,” “Ripley,” and “All of Us Strangers,” slips in and out of the various characters of “Uncle Vanya” (as adapted by Simon Stephens) with almost no help from costume, staging, or lighting. Instead, he relies on voice modulation, posture, and subtle shifts in tone to distinguish between Chekhov’s emotionally paralyzed figures.

While Scott is magnetic, expressive, and often heartbreakingly raw, the production is often hard to follow. The characters blur together in ways that are not always dramatically intentional. A viewer unfamiliar with the original text might quickly lose track of who is speaking to whom. Even those who know “Uncle Vanya” well (it is one of the most frequently-revived dramas in the world) might find themselves mentally retracing their steps to figure out whether we’re currently hearing from Sonya, Astrov, or Yelena.

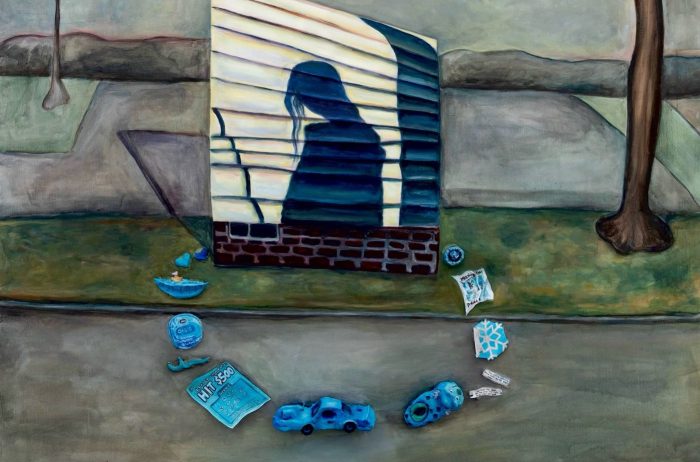

Stephens’ adaptation pares down Chekhov’s dialogue into a streamlined, 90-minute memory play. But in doing so, it flattens the interpersonal dynamics. This “Vanya” is not a drama of social tension and thwarted love. As directed by Sam Yates, it’s a solo lament, delivered with devastating conviction but limited clarity. The staging is spare and somber: a cluttered space that has elements of a study, kitchen, and basement playroom. The result is an immersive tone poem of regret, beautifully acted but emotionally diffuse.

After attending the show, I watched a filmed version of the London production that is available to stream via the National Theatre at Home app. Because the subtitles noted whenever a new character began speaking, it became much easier to follow.

If “Vanya” is a study in restraint, “Dorian Gray,” as adapted and directed by Kip Williams, is an all-out visual and technological assault on the senses. Australian actress Sarah Snook—Emmy-winner and breakout star of “Succession”—plays 26 characters, including the doomed title character, the artist who created the portrait that becomes a window into his tattered soul, the older patron who encourages Dorian to indulge in a hedonistic lifestyle, the young actress whom Dorian woos and then abandons, and a variety of other socialites and figures of London.

Snook performs live while interacting with prerecorded footage of herself, often talking to multiple versions of herself projected on screens that rotate, split, and reframe the stage like a cinematic puzzle box. The production uses video design, sound editing, and live feeds to astonishing effect, creating a rapid-fire, kaleidoscopic narrative experience that feels more like a film or experimental multimedia project than a play.

As dazzling as it is—and it really is—it raises the question of whether it is theater. While there have been many other shows that capitalize on live and prerecorded filming (including the current Broadway revival of “Sunset Boulevard”), “Dorian Gray,” which relies primarily on footage appearing on a multitude of screens, could easily be adjusted to run without Snook (who is assisted by a tech crew) appearing live onstage.

There’s no denying the virtuosity of Snook’s performance—or rather her performances. She’s fierce, funny, and completely in control of an almost impossibly complex machine of cues and quick changes. But it’s hard to escape the feeling that the tech is doing a lot of the storytelling heavy lifting.

Wilde’s novel about vanity, corruption, and the perils of surface beauty fits neatly into this digitally fractured, image-obsessed staging. But the emotional core—the horror of Dorian’s moral collapse—gets lost amid the technological dazzle. You leave the theater impressed but perhaps not deeply moved. It’s a tour-de-force performance inside a funhouse mirror, breathtaking but chilly.

“Vanya” and “Dorian Gray” sit at opposite ends of solo theater, minimalist versus maximalist. They are fascinating experiments in what solo performance can do—but also reminders of what it can’t.

“Vanya” runs at the Lucille Lortel Theatre through May 11, vanyaonstage.com. “The Picture of Dorian Gray” runs at the Music Box Theatre through June 15, doriangrayplay.com.