The city’s largest landlords might have a bit more time to decarbonize their buildings under new rules published Tuesday pertaining to the implementation of Local Law 97, although some environmental advocates are accusing the Adams Administration of “gutting” the landmark climate law.

The 2019 law requires buildings over 25,000 square feet to start meeting strict regulations on carbon emissions next year, and obligates landlords to retrofit their buildings should they fail to comply; by 2030, the city’s largest buildings must have reduced their carbon emissions by 40% compared to 2005 levels, and by 2050 emissions must be reduced by 80%. Buildings account for about 70% of the city’s carbon emissions.

The Department of Buildings’ (DOB) long-awaited rules address a major facet of uncertainty for property owners by spelling out what it means for landlords to make a “good faith effort” to decarbonize their buildings, mitigating their penalties even if they fail to comply. They also spell out a fine for landlords of $268 per ton of carbon spewed into the atmosphere beyond their buildings’ emissions limit.

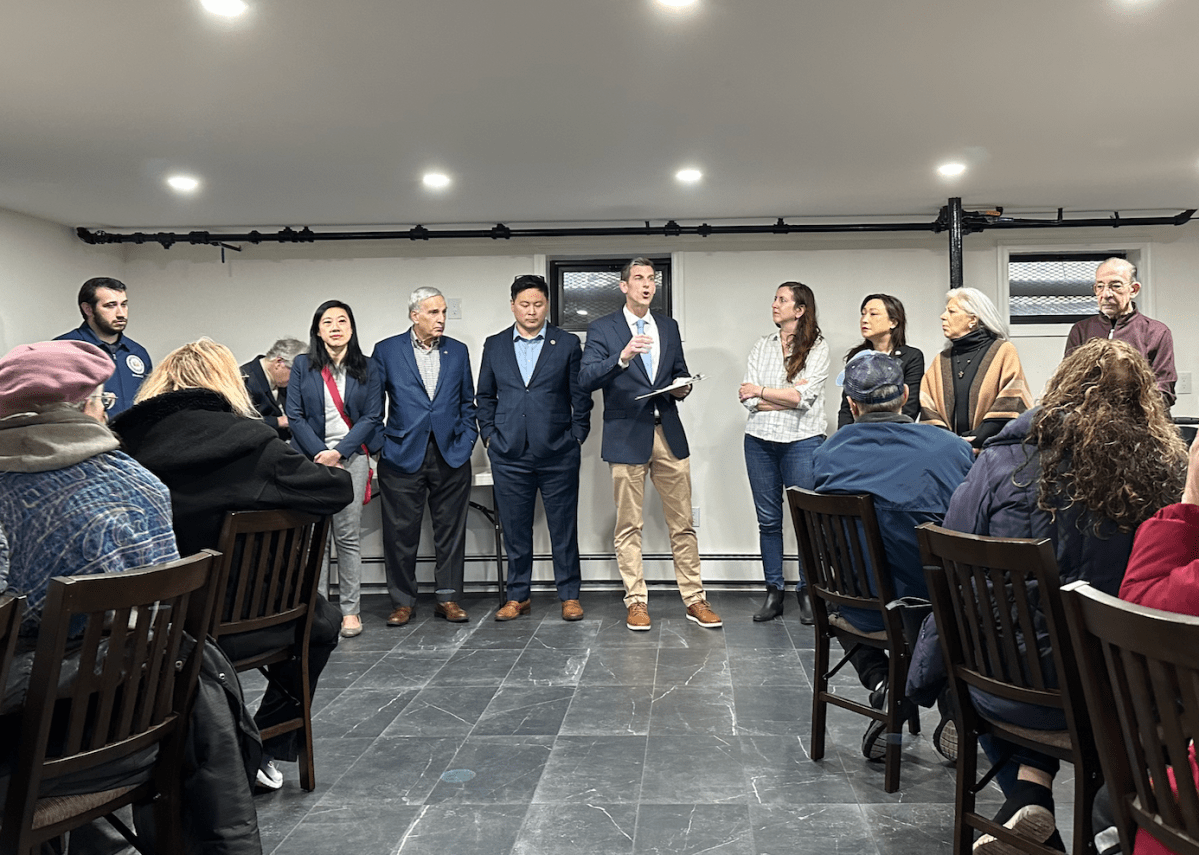

“Enforcement of Local Law 97 is one of the most significant and complex mandates we have at our department,” said DOB Commissioner Jimmy Oddo. “The comprehensive Getting 97 Done plan and the latest tranche of proposed agency rules were designed to maximize climate mobilization, by assisting property owners who are working to comply with the law while also giving real teeth to our enforcement procedures.”

Only about 11% of the 40,000 buildings covered under the law are expected to be out of compliance come next year, but that still represents thousands of buildings that need to reduce their emissions faster. Many of the non-compliant buildings are older co-ops and condo developments, provoking anxiety among owners.

Under the rules, those non-compliant buildings can effectively delay their compliance deadline, and avoid penalties, from 2024 to 2026 by proving a “good faith effort,” through agreeing to submit a detailed “decarbonization plan” to reduce emissions. Such a plan involves a landlord undergoing an independent “energy audit” of their property that proves that they are undertaking efforts to decarbonize. They must itemize the alterations and retrofits needed and provide evidence of a timeline to complete those projects and that they have been adequately financed.

“Of course, I would prefer that all buildings comply in 2024,” said John Mandyck, CEO of the nonprofit Urban Green Council, who gave high marks to the DOB’s rules. “But the fact of the matter is they’re just not for many reasons. COVID, supply chain problems, the length of getting regulations out. So we’re left with a choice, either fine them and forfeit all of the carbon savings, or we find a practical way to get them into compliance.”

Other groups lending their support to the new rules include the Natural Resources Defense Council, the New York League of Conservation Voters, the Association for Affordable Energy, and the Regional Plan Association.

The administration expects 15,000 buildings will need major capital work to comply with the strict 2030 limits. City Hall estimates that could cost up to $15 billion and create 140,000 jobs.

Those buildings undertaking a decarbonization plan will be prohibited from purchasing “renewable energy credits” (RECs) to offset their emissions. Purchasing a REC essentially means a landlord avoids penalties for carbon emissions beyond their limits by investing in the delivery of renewable energy to the New York City grid, which is still heavily reliant on fossil fuels.

RECs are among the most controversial aspects of the law, with some environmental advocates contending they’re a mechanism for deep-pocketed landlords to buy their way out of compliance.

The rules do not spell out any limits on the purchase of RECs for buildings that don’t undertake a decarbonization plan, but RECs are also not expected to be available at all until at least 2026.

Two massive transmission line projects are expected to bring renewable energy to the city in the coming years, but one of them, the Champlain Hudson Power Express — which will transmit hydroelectric power from Canada to New York City — has already seen its anticipated completion delayed from 2025 to 2026. The other, Clean Path NY, which will bring upstate solar and wind energy to the Big Apple, isn’t set for completion until 2027.

A DOB spokesperson suspects that purchasing RECs would be more cost-prohibitive than pursuing upgrades either way once they become available.

Mandyck says the administration’s REC limits ensure landlords will make investments in their buildings instead of just buying credits.

“We need to balance the fact that we need to green our grid, at the same time we need to balance the fact that we need to invest in our buildings to lower carbon emissions,” said Mandyck. “I think the approach DOB has taken today is the right balance, which is if you don’t comply in 2024 and you need two extra years, then you need to invest in your building to do that, you can’t just go buy RECs.”

Other environmental advocates are not so optimistic, though. In a joint statement, four environmental groups — Food & Water Watch, New York Communities for Change, New York Public Interest Research Group, and TREEage — accused Mayor Eric Adams of kowtowing to a real estate industry campaign to weaken the law, which represents one of the largest and most expensive mandates on landlords in the city’s history.

“It’s been a summer of unrelenting heat waves, flooding and other dangerous climate events, yet Mayor Adams wants to give a huge gift to New York’s top corporate polluters — the real estate lobby, who are his largest campaign donors,” the environmental groups said. “If his proposed rules are adopted, New Yorkers could lose tens of thousands of jobs, air pollution could increase by millions of tons per year, and energy bills could get even higher because landlords will be allowed to avoid upgrading their dirty, polluting buildings to high energy efficiency.”

The groups say the rules on RECs are vague, and could provide a “loophole” for well-heeled landlords to not comply, especially after they become available and can allow owners to reduce their penalties.

“Mayor Adams is all too willing to let his billionaire campaign donors delay penalties and use loopholes to evade New York City’s landmark climate jobs law, Local Law 97,” the groups said. “Our communities need pollution reductions, good jobs and lower energy bills.”

Reached for comment, a spokesperson for DOB said the agency is far from done with rulemaking for the mammoth climate law, with additional rules set to come out for good faith efforts in further compliance periods and on the governance of the REC market.

The rules were rolled out along with a suite of moves the administration plans to take to help buildings get into compliance, called “Getting 97 Done.” Most notably, the city wants to clarify that the state’s new J-51 tax incentive for residential renovations can be used to cover the costs of complying with Local Law 97, and also to leverage state money for energy efficiency upgrades and federal tax incentives under the Inflation Reduction Act.

This story was updated with more accurate information on the Clean Path NY transmission line.

Read more: NYC Pilots Containerized Trash Collection in Harlem