A state appellate court revived a lawsuit seeking to overturn New York City’s Local Law 97, potentially imperiling the city’s landmark statute regulating large buildings’ carbon emissions.

The New York state Supreme Court’s First Appellate Division ruled on May 16 that city lawyers hadn’t proven the 2019 law — which requires the city’s largest buildings to meet strict new emissions limits — is not preempted by the state’s own overarching climate statute, the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA). The ruling was first reported Thursday by Crain’s New York Business.

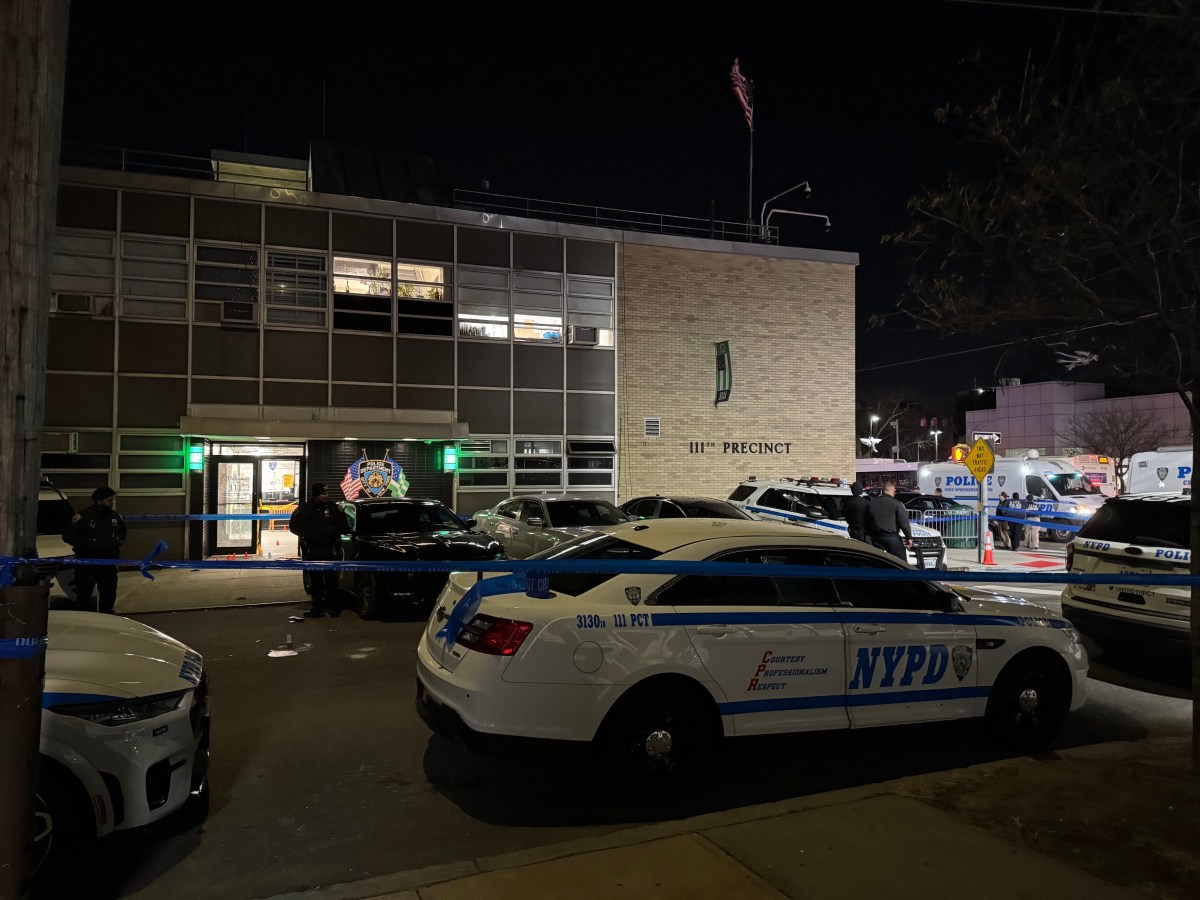

Two co-op complexes in Queens, Glen Oaks Village and Bay Terrace, filed the lawsuit in 2022, arguing that the law would unduly burden middle-class homeowners with excessive penalties; the state Supreme Court last year.

But while the Appellate Division upheld the dismissal of most of the arguments — like the law being an undeclared tax and a violation of constitutional due process — the tribunal of jurists, in its May 16 ruling, said the question of preemption deserves greater scrutiny.

“There was a conflict between the two, because the state law calls for different things, it calls for different remediation methods and the city law, Local Law 97, just completely comes in conflict with the state law,” said Warren Schreiber, board president at Bay Terrace, a 200-unit co-op complex in Bayside. “One of the big conflicts is the penalties imposed by Local Law 97, those were never part of the state law. And that was always the main argument. And also the state law did not do away with past actions.”

The case will now return to the trial court level.

A spokesperson for the city’s Law Department said the Adams administration intends to appeal the decision in court.

“The most important thing New York City can do to reduce our impact on climate change is decrease our greenhouse gas emissions. The City stands by its bold, world-leading climate law and will continue to defend it in court,” said the spokesperson, Nicholas Paolucci. “Local Law 97 remains in effect and the City will continue to move forward with implementation while advancing programs, like the NYC Accelerator, to support building owners.”

The Department of Buildings, which is implementing the law, deferred comment to the Law Department.

Local Law 97 requires most Big Apple buildings over 25,000 square feet to retrofit their properties to meet strict new limits on carbon emissions or pay steep penalties per ton of extra carbon emitted. Those limits first went into effect this year — though with a two-year reprieve for property owners making a “good-faith effort” to decarbonize their buildings. By 2030, covered buildings will have to have cut their emissions by 40%.

Despite the seemingly tall order of the task, DOB has said the vast majority of covered buildings, about 90%, had met or were on track to meet their emissions thresholds this year. The law, which was intended to create scores of union jobs cleaning up polluting properties, has spurred a cottage industry in the city for landlords to electrify their buildings, and the city and state have announced new incentives and credits to make buildings cleaner while dulling the pain it might inflict on the wallet.

‘We don’t have this kind of money’

Despite all that, some co-op and condo owners still feel the law is an unachievable mandate that will bankrupt them.

“Everyone wants a clean environment, most co-ops do everything they can to do that,” said Bob Friedrich, board president of Glen Oaks Village. “But you can’t create artificial dates and expect us to pay this kind of money, we don’t have this kind of money.”

The co-op owners are pinning their hopes on a bill in the City Council, Intro 772, which would eliminate existing penalties for noncompliance through 2036 and reduce them through 2046, and allow co-op complexes to include green spaces on their property when calculating their greenhouse gas thresholds per square foot, potentially reducing their penalties further. Intro 772 has 25 co-sponsors in the Council, one short of the majority of the body.

Co-op owners, like the plaintiffs, say the bill would make it easier and less financially burdensome to meet the mandate. Environmentalists have blasted the bill as watering down the original statute as the need to take bold action on climate change becomes more urgent.

Local Law 97 remains in effect as the suit again winds its way through the courts. But environmentalists fear that allowing the lawsuit to continue could chill landlords’ drive to quickly decarbonize.

“Climate change isn’t waiting for us to dither through litigation,” said John Mandyck, CEO of the Urban Green Council. “People are gonna read about it and misinterpret that they can delay action when, in fact, the law is still moving forward. So I’m worried about delay.”

The plaintiffs argue that the CLCPA preempts New York City’s, or any other municipality’s, ability to enact climate regulations, a legal doctrine called “field preemption,” said Amy Turner of Columbia University’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.

“I think the idea that Local Law 97 would be preempted by the CLCPA would be entirely overbroad, inconsistent with the legislature’s intention when it passed the CLCPA,” said Turner. “It didn’t say anything about preempting local laws.”

By arguing that the CLCPA field preempts local climate law, the plaintiffs are saying “the legislature has legislated so broadly in a subject area field, that no other local law can go into effect in that field,” Turner explained. “And that’s pretty rare.”

Former Assemblymember Steven Englebright, a Democrat who represented Suffolk County till 2022 and the original sponsor of the CLCPA, also said he finds the preemption argument questionable.

“The state legislation, CLCPA, did not preempt localities acting,” Englebright said through his former counsel, Steve Liss. “The state law sets the floor, not the ceiling.”

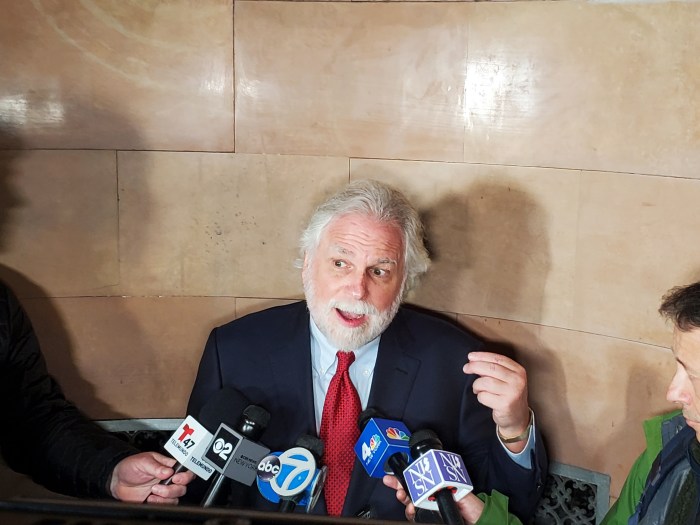

Randy Mastro, the prominent litigator at King & Spalding representing the plaintiffs, would not explain further the field preemption argument when reached out to by amNewYork Metro, saying the “briefs and appellate opinion speak for themselves.”

Mastro’s involvement in the suit is also raising alarms among environmentalists, considering he is up for nomination to be the city’s Corporation Counsel, the top lawyer defending the administration in court and leader of the Law Department. That means Mastro is currently fighting in court with Sylvia Hinds-Radix, the current holder of the office, while hoping to obtain her job that oversees the case she is defending against him and his firm.

Asked about this potential conflict of interest, Mastro confirmed he would recuse himself from the Local Law 97 case if he were confirmed by the City Council, which already appears a tall order anyway. Despite not being formally announced as the nominee, City Council opposition to the nomination is already substantial.

That’s in large part due to his record in environmental litigation, which includes defending Chevron from having to pay a $9.5 billion judgment to Ecuador over oil pollution poisoning a rainforest and local indigenous communities, as well as currently representing New Jersey in its bid to overturn New York’s congestion pricing program.

It also remains unclear who is paying Mastro’s retainer fee in the case. Both Mastro and Schreiber declined to comment on that.

Even if he did formally recuse himself as Corporation Counsel, Turner still sees cause for alarm.

“Even if he did recuse himself from that one piece, it’s a matter of what political resources is he putting behind different cases in his office,” said Turner. “And I worry that he would pull back staffing resources with respect to cases that he has been on the other side of. And that to me is a potentially huge conflict of interest.”

Updated with comment from the Law Department.