The city’s Health Department allowed the New York City Housing Authority to cover up test results showing hazardous levels of lead paint in a residential unit and skirt responsibility to remediate the conditions, even after a child was hospitalized with severe lead poisoning, a new lawsuit filed by the child’s mother alleges.

Ikasha Whitaker, a resident of NYCHA’s East River Houses in East Harlem, said in her lawsuit filed in Manhattan Supreme Court on Friday that the Health Department (DOHMH) allows NYCHA undue deference in challenging lead test results than it does to private landlords, despite the public housing agency’s history of covering up lead violations and its use of flimsy technology to test for lead hazards.

Whitaker says she experienced the consequences of this firsthand in April, when her 3-year-old child was hospitalized with blood-lead levels of 44 micrograms per deciliter, constituting severe lead poisoning and requiring chelation therapy. Lead is particularly dangerous for young children, for whom it can cause lifelong developmental problems.

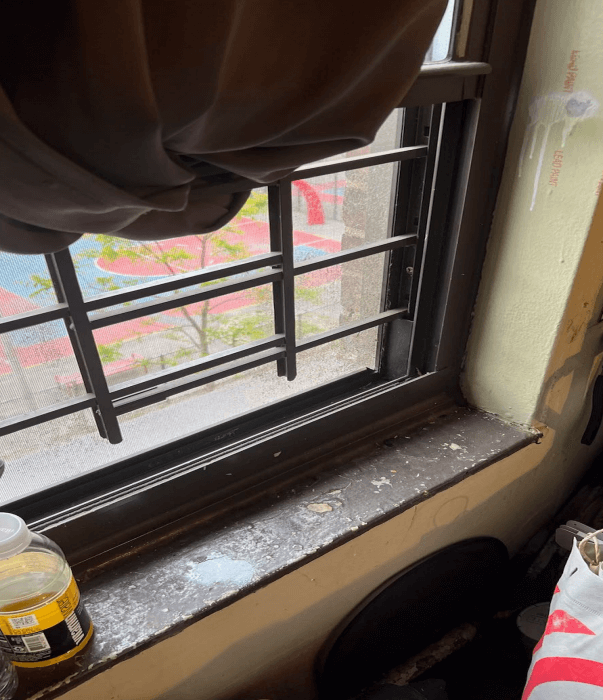

After the child’s hospitalization, DOHMH conducted X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) testing for lead hazards in Whitaker’s apartment, finding chipping and peeling paint on 22 surfaces, with particular concern on windowsills easily accessible to the toddler. On April 19, the Health Department issued a “Commissioner’s Order to Abate Nuisance” (COTA) to NYCHA and ordered the authority to correct the hazards within five days.

That same day, NYCHA informed DOHMH that it intended to contest the results, despite not yet having conducted its own lead tests. On April 24, NYCHA conducted its own tests, using analysis of paint chips rather than XRF; Whitaker says this is a less reliable test that’s more prone to error. Furthermore, Whitaker believes NYCHA is unable to impartially conduct the tests since the authority is her landlord, and thus an interested party.

Nevertheless, on April 26, DOHMH rescinded 16 of the 22 initial violations, allowing NYCHA to leave most of the apartment’s hazardous lead paint in place despite the toddler’s condition. A spokesperson for NYCHA told amNewYork Metro that the family has been temporarily relocated while the remaining hazards are abated.

“The health of public housing families is among NYCHA’s foremost priorities, and we remain resolute in our commitment to keeping children safe from lead paint,” said the NYCHA spokesperson. “NYCHA has been working cooperatively with this family to relocate them and provide accommodations while a team of certified lead professionals abate the apartment and ensure that it is lead-free.”

Whitaker and her lawyer say the Health Department’s rescission was “arbitrary and capricious,” and contend it was in violation of the department’s own Health Code, which states that when an owner objects to DOHMH lead test results, the department can rely on its own testing if it believes that “will be more protective of the health of a child with an elevated blood lead level.”

Environmental hazard consultant Marco Pedone, CEO of Environmental Management Solutions of New York, said in an affidavit to the court that the Health Department’s Viken XRF device is “the gold standard” in lead paint detection, and that paint chip analysis is far more prone to human error resulting in dilution of lead concentration. Pedone said the records NYCHA submitted to DOHMH “raise questions as to whether the proper sample size was taken.”

“If DOHMH will rescind its own XRF testing based upon unvalidated paint chip collection performed by an interested party, then what value does DOHMH’s XRF testing provide,” wrote Pedone. “In this case, a young child living in the apartment had been diagnosed with an elevated blood lead level of 44 µg/dL and DOHMH’s determined that the conditions constituted a lead hazard only to rescind its own testing in favor of inferior results taken by an interested party.”

Pedone’s firm was contracted by Whitaker’s lawyer to conduct a third-party lead analysis using XRF, and reported results it says are consistent with the Health Department’s initial findings.

Whitaker is petitioning a judge to reinstate the 16 violations DOHMH tossed to the wayside, and direct the department to enforce its commissioner’s order against NYCHA.

The supposed cover-up is just business as usual at NYCHA, Whitaker argues.

“That NYCHA objected to DOHMH’s COTA herein was predictable. Upon information and belief, it is NYCHA’s business practice to routinely challenge DOHMH’s determinations found in COTAs,” wrote her attorney, Reuven Frankel. “Such practice was instituted as a means to improperly mitigate their financial exposure in future lawsuits resulting from lead poisoning of its tenants caused by NYCHA’s well documented negligent management of its properties.”

The filing links to a 2018 New York Times article which found, over an eight-year period, NYCHA challenged 95% of lead abatement orders from the Health Department. The Health Department backed down in 75% of cases that were challenged. By contrast, private landlords contested only 4% of similar orders in the same timeframe.

“NYCHA should receive the same treatment as any other landlord who failed to maintain an apartment in a reasonably safe manner resulting in a child’s lead exposure,” said Frankel. “DOHMH should not extend preferential treatment to another agency at the expense of the health and welfare of a lead-poisoned child.”

NYCHA’s mismanagement and cover-ups of lead paint hazards were among the major issues leading the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development to install a monitor over the agency in 2019, under a consent decree that last month the feds moved to extend for an additional five years.

NYCHA leadership during the Bloomberg and de Blasio administrations routinely filed false certifications that it was conducting mandatory lead inspections at its 335 properties, home to 360,000 New Yorkers, and was found to have covered up hundreds of instances of child lead poisoning at NYCHA properties. The monitor found thousands of apartments contained dangerous levels of lead.

Health Department spokesperson Patrick Gallahue denied the contention that NYCHA is treated differently than any other landlord, noting the agency will rescind orders if the lead concentration is discovered to be in a metal surface rather than paint, as metal does not chip.

“Between 2005 and 2020, there has been a 93% decrease in the number of children with blood lead levels of 5 mcg/dL or greater in New York City,” said Gallahue. “We investigate every elevated blood lead level in a child so that we can identify potential exposures and correct those conditions.”

The office of the NYCHA monitor, Bart Schwartz, declined to comment.

The original 2019 consent decree between NYCHA and HUD requires the housing authority to abate all lead in its properties by 2039, with half of that abatement expected to be completed by 2029.

Testing of NYCHA apartments, especially those where children under 6 reside or spend time, has been beefed up considerably, with the agency claiming it’s tested 115,000 units since 2019 at a clip of 700-800 per week. The agency has retested 32,000 units to comply with city regulations that halved acceptable lead concentrations in samples.

“We have tested more than 115,000 apartments for lead and are currently testing and abating several hundred more every week – a historic number for any landlord of this scale – while setting goals far and above our legal obligations,” the NYCHA spokesperson said. “We will continue to accelerate our abatement work and prioritize the health and safety of young children.”

About 40% of the apartments tested under the more stringent guidelines came back positive for lead.

The agency and its vendors completed just over 1,000 lead abatement projects in the first ten months of 2022, Schwartz reported in his quarterly monitoring report last November.

The Law Department said it would “review the case once it’s served.”

Read more: Groundbreaking for massive affordable housing at Willets Point