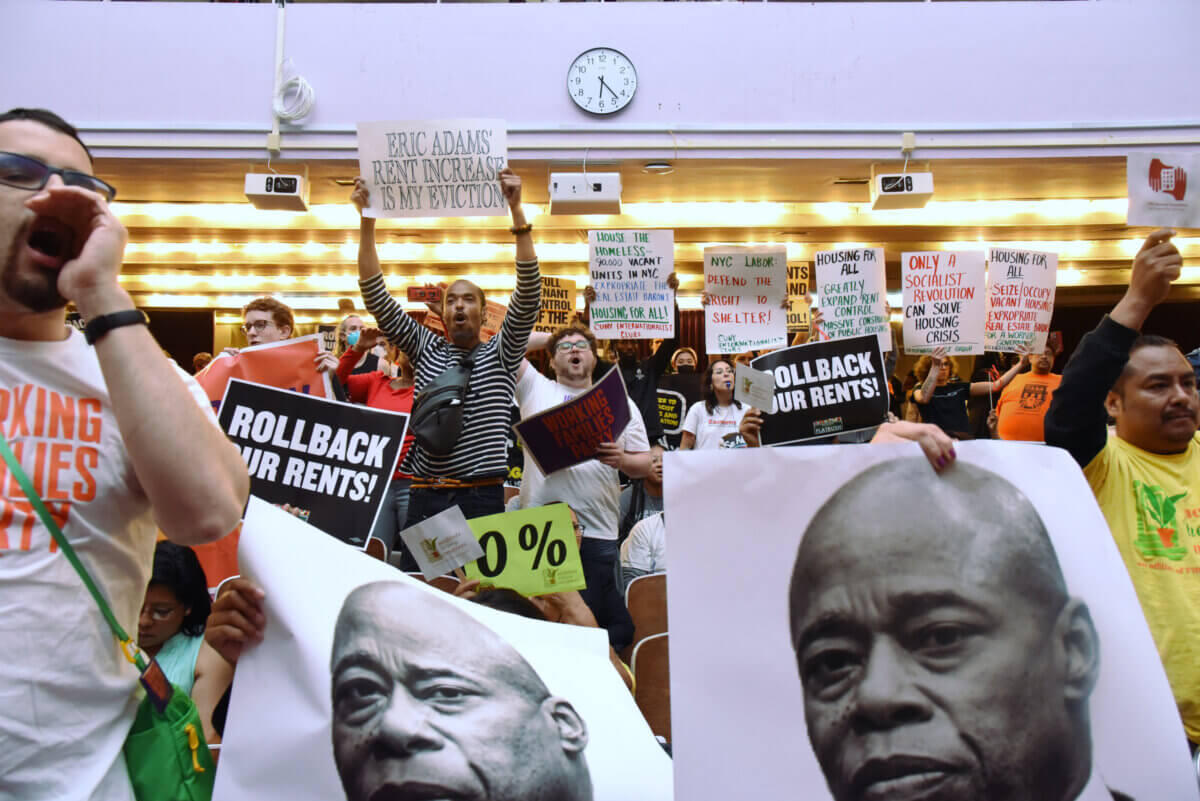

The Rent Guidelines Board on Wednesday voted to hike rents for New York’s more than 1 million stabilized tenants — earning jeers from lessees seeking a freeze or rollback in leases.

By a 5-4 vote, the board approved a 3% rent increase for one-year leases, and bifurcated increases for two-year leases of 2.75% in the first year, and 3.2% of the newly increased rent in the second year. That leaves rent close to 6% higher after two years, although the mayor’s office notes the overall amount of rent paid to the landlord in those two years would increase only 4.5%.

Both of the board members repping landlords voted against the increase, having sought higher hikes, as did some members repping the general public. Meanwhile, members representing both tenants and others repping the public voted in the affirmative.

In a statement, Mayor Eric Adams — who appoints all nine members of the board — said the board had found the “right balance” in the vote.

“I want to thank the members of the Rent Guidelines Board for their critically important and extremely difficult work protecting tenants from unsustainable rent increases, while also ensuring small property owners have the necessary resources to maintain their buildings and preserve high-quality, affordable homes for New Yorkers,” hizzoner said in a statement. “Finding the right balance is never easy, but I believe the board has done so this year — as evidenced by affirmative votes from both tenant and public representatives.”

After the board approved in May an initial plan that could have seen hikes of up to 7%, Mayor Adams had said that was not “appropriate this year.”

But tenants argued that no rent increases are appropriate, given the financial calamity of the COVID-19 pandemic and a spiraling housing affordability crisis throughout the Big Apple.

“If my rent went up like that amount, then I’m gonna have to decide how much food I’m gonna cut back on, what other things I’m gonna cut back on, in terms of paying the rent,” said Julia Phillips, who is retired and has lived in a rent-stabilized Crown Heights unit for over 30 years, at the Board vote at Hunter College Wednesday evening.

Still, landlords argue that larger rent increases are needed on stabilized units so that they can properly maintain them, amid increases in the cost of inputs like property taxes, fuel, and insurance.

“Every year, we see the same drama unfold, and nothing ever changes,” said Jay Martin, executive director of the Community Housing Improvement Program, a rent-stabilized landlord trade group currently petitioning the Supreme Court to end rent stabilization in New York. “The RGB puts data out there which is largely ignored, tenant advocates and politicians scream and shout, and rent-stabilized housing gets defunded. If we continue on this trajectory, there won’t be any rent-stabilized housing left for people to live in.”

Phillips ridiculed that notion, though, noting that her own landlord has remained neglectful no matter how much the Board raises rents in a given year.

“It’s ridiculous what they want to do,” she said. “They want to raise the rent but, especially for the people who live in the same apartment for a lot of years, they’re very slow to do the repairs. And if they do do any repairs, they don’t last very long.”

The data relied upon for this year’s increase, which is smaller than last year’s for one-year leases but larger for two-year ones, analyzed increases in costs from 2020 to 2021, a period when the COVID-19 pandemic led to a rare drop in New York’s rental prices. Rents have since rebounded to historic highs.

Meanwhile, over a 30-year period, the RGB’s data shows landlords’ “net operating income,” a term for profits, for rent-stabilized buildings increased by just shy of 50%, outpacing both costs and rents.

Doing the math

Under the approved increase plan, rent-stabilized tenants with one-year leases will see their monthly payments go up 3% — meaning that a lessee paying $1,500 a month now will see their bill increase by $45 per month.

Lessees with two-year agreements would see a 2.75% increase in the first year; if they pay $1,500 a month now, that means their bill would increase by $41.25 per month. The next year, their new rent of $1,541.25 would then be increased another 3.2%, or $49.32, bringing the new monthly rent in year 2 to $1,590.57.

That would amount to a 6% increase over their current rent after two years.

‘Severely rent burdened’ already

As for tenants, the RGB’s Income and Affordability Study found more than a third of the city’s renters are paying at least half of their income in rent to their landlord, a situation the city defines as “severely rent burdened.” Just under 40% of rent-stabilized tenants are considered severely rent burdened.

Eviction filings increased 167.8% in 2022, after the state rolled back its pandemic-era eviction moratorium, and many tenants are going before judges without a lawyer.

The city’s homeless shelters are regularly boarding up to 80,000 people per night, the highest levels ever recorded, especially as waves of asylum seekers arrive in the city. Many more homeless people sleep on the streets and subways or are couch-surfing.

In April, the United Way’s “True Cost of Living” study found more than half of New Yorkers are struggling to afford their basic needs.

One of the board’s tenant members, Adán Soltren, argued that the Board is ignoring its mandate — enshrined in the original rent stabilization law — to protect tenants from displacement and preserve the city’s affordable housing, in favor of ensuring constant returns for landlords.

“It’s what the board is supposed to adhere to when making its decisions,” said Soltren. “Be that as it may, it becomes increasingly evident year-in and year-out that not everyone on this board understands and agrees with that charge.”

Still, both tenant members opted to vote for the increases even as tenants in the audience demanded a rent freeze or rollback. Outside the venue, the other tenant member, Genesis Aquino, explained to amNewYork Metro that the tenant members were put in a tough spot, as the proposal voted through was the lowest increase they could negotiate that would get enough aye votes from public members.

“I feel like I was put between a wall and a hard place,” said Aquino, the only rent-stabilized tenant serving on the board. “That was the lowest we were going to get. What I know is, some members of the public did not want to vote for that, and I think you saw they voted against it. We did not necessarily have the votes.”

Their tale of two mayors

While the RGB is a nominally independent body, its votes are typically a reflection of the housing priorities of an incumbent mayor, who appoints all of the board’s members.

Under former Mayor Bill de Blasio, rents were frozen on several occasions, but Adams has publicly expressed more sympathy for the plight of “mom and pop” landlords. The two increases under his tenure are the largest since the Bloomberg administration.

Tenants at the board certainly weren’t buying the notion that the board is separate from the mayor, with protesters carrying signs bearing Adams’ face and a nametag reading “Landlord.” One rent-stabilized tenant, Basil — a Williamsburg resident who declined to give his last name — held a sign reading “Eric Adams’ rent increase is my eviction.”

“There’s not enough money to pad yourself six months to make emergencies like this,” said Basil. “Everybody knows, it’s statistics at this point, the people don’t have $400 for an emergency. So when you eat into that with a $170, $200, $250 increase per month, it’s just impossible. My margins are just so narrow.”

“I don’t know why the mayor should have such compassion for the landlords. And he thinks the landlords are suffering,” said Jean Folkes, a rent-stabilized tenant from Ditmas Park. “Did he ask the tenants how they are suffering?”

Brooklyn City Councilmember Chi Ossé, who was present at the meeting, told amNewYork Metro that the board is a reflection of Adams’ priorities, and argued the board is in need of reform, suggesting either the City Council should get confirmation power over members or that it should be directly elected by the public.

“The Rent Guidelines Board could be a good board for tenants depending on who your mayor is,” said Ossé, who reps Bedford-Stuyvesant and Crown Heights. “And right now it’s not a good board for tenants because of who our mayor is.”

In May, Ossé joined other elected officials and advocates in storming the stage and disrupting proceedings as the board voted on its preliminary range of increases, a move that landlord reps and lobbying groups described as intimidating. At Wednesday’s meeting, the Board banned the presence of noisemakers and drums in the venue, and blocked off the front of the auditorium with police tape manned by CUNY security guards.

The measures did not stop audience members from relentlessly booing the proceedings, shouting over deliberations, and shaming board members.