The historic, multi-state $462 million settlement with electronic cigarette company JUUL Labs that New York Attorney General Letitia James announced last week aims to finally get the nation’s youth e-smoking epidemic under control.

The attorneys general from New York, California, Colorado, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Mexico, and the District of Columbia sued JUUL for causing a nationwide youth vaping epidemic. New York State will receive $112.7 million over an eight-year period, with $14 million to arrive in the next three months.

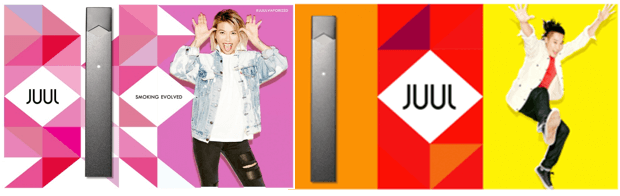

James announced the lawsuit, filed in New York County Supreme Court, in November 2019. The lawsuit brought claims of JUUL’s “deceptive and misleading marketing of its e-cigarettes” and that JUUL “illegally sold its products to minors through its website and in third-party retail stores throughout the state.” The lawsuit pins “large numbers of New York youth” becoming addicted to nicotine on JUUL and its advertising campaign.

“Taking a page out of Big Tobacco’s playbook, JUUL misled consumers about the health risk of their products,” James said last week. “JUUL targeted youth by glamorizing vaping with colorful ads featuring young models and flashy parties in New York City and the Hamptons, all while downplaying the harmful effects of vaping.”

When JUUL launched in 2015, e-cigarette use in New York City high school students increased from 8.1% in 2014 to 23.5% by 2018, James stated in the announcement. This “proliferation of vaping led to a national outbreak of severe vaping-related illnesses” as well as the death of 17-year-old Denis Byrne Jr. from The Bronx. Byrne Jr. became the first young person in the country and the first in New York State to die from an e-cigarette-related illness.

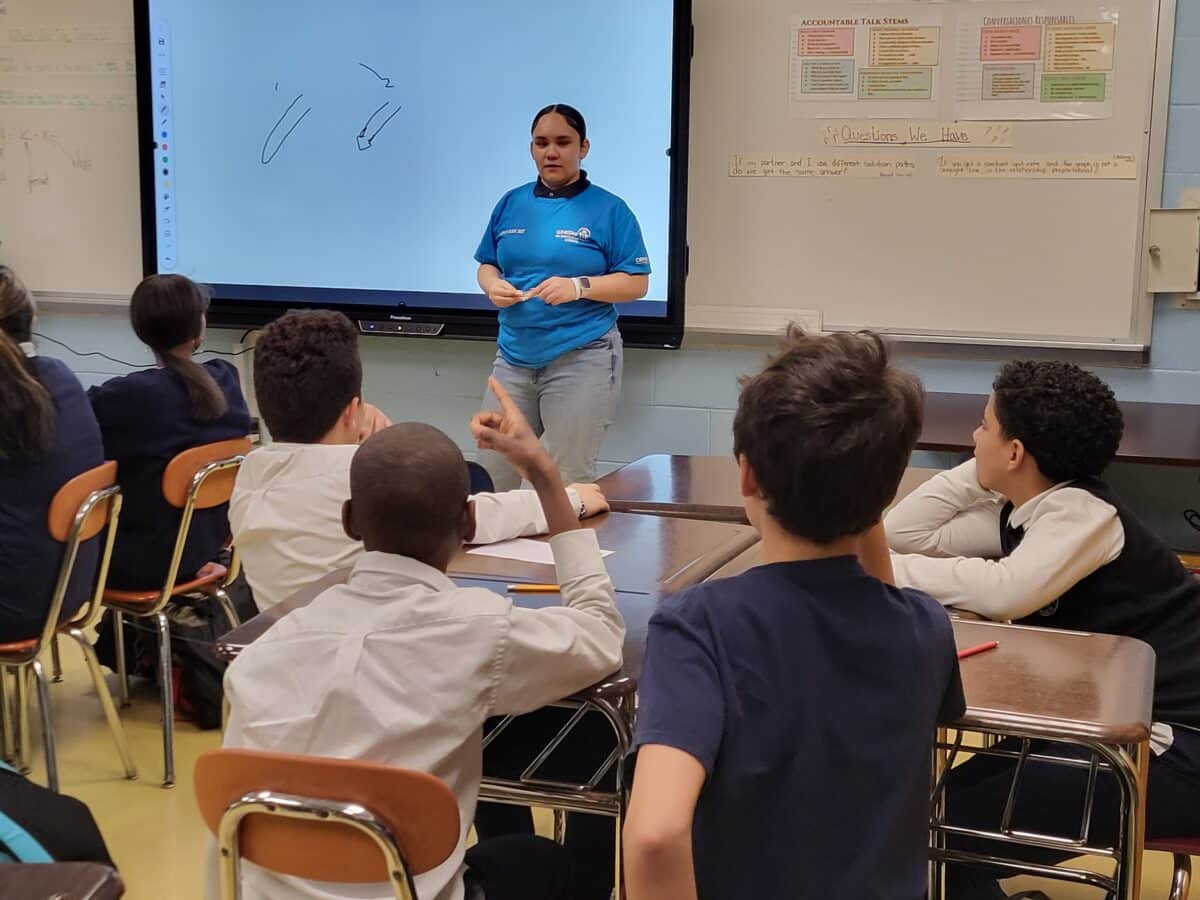

James also said that a JUUL representative engaged with at least one New York City school and falsely told high school freshmen that its products are safer than cigarettes. One of those schools was Dwight High School in the Upper West Side of Manhattan, said Halimah Elmariah, deputy press secretary for the New York State Attorney General.

The latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data from 2022 shows that nationwide minors and youth adults still have the highest e-cigarette usage rates of any age group. More than one in five high school students across New York reported that they vaped regularly in 2020, according to the state’s health department.

Four years after JUUL launched, the nationwide vaping trend had led to a national outbreak of severe vaping-related illnesses, with more than 2,500 hospitalizations.

Smoke shop workers weigh in

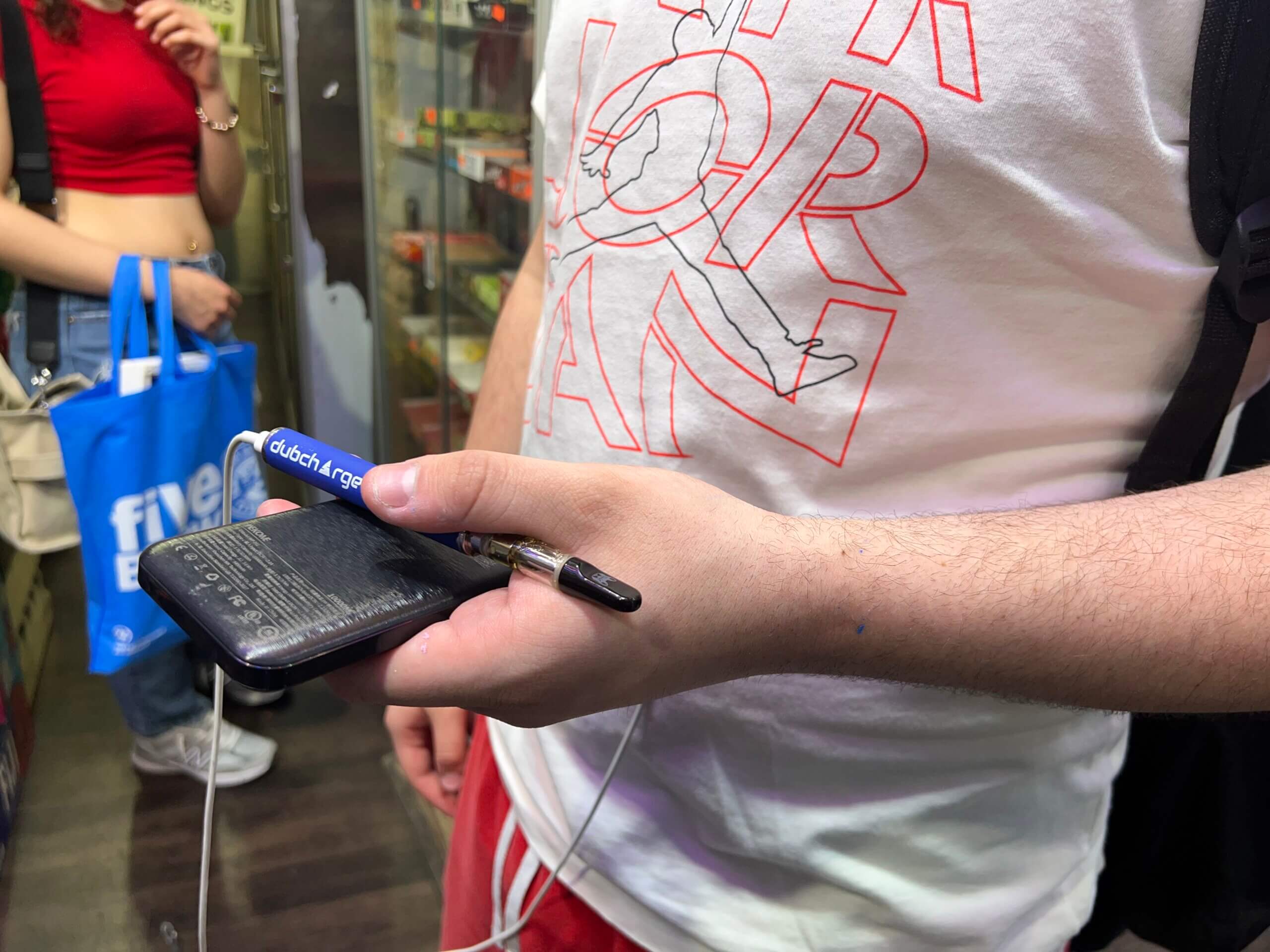

Julio Galay, who works at a smoke shop in Chelsea, remembered the first time he saw people in college using JUUL. Most of the time, people were flaunting their JUULs on the Snapchat app. In the past several years, he’s noticed vaping usage transition from “older teens to middle school kids.”

“I saw middle school kids and I’m just like, ‘You don’t even know what’s going on. You don’t even know what you’re putting into your body,'” Galay said. “As much as your body is telling you that it feels good, it’s just tarnishing your lungs.”

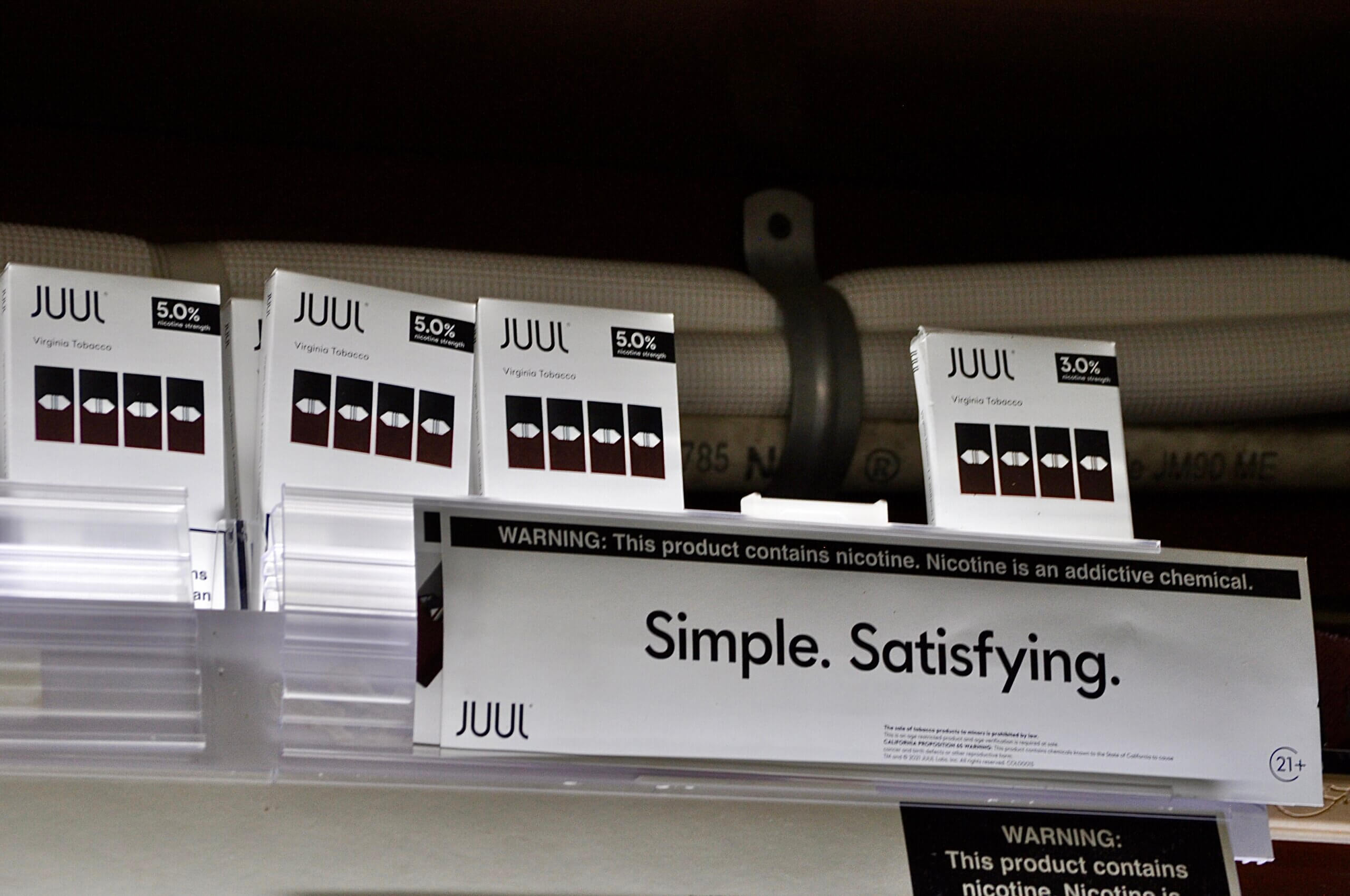

The shop Galay works at keeps JUUL products behind the counter on a top right shelf. When Galay’s boss found out about the JUUL lawsuit, he said his boss panicked about the impact to the store and his store’s most popular JUUL customers: tourists from different countries.

Galay said he used nicotine during lower points of his life, when he was feeling pain for a long period of time. He’s since dropped nicotine and goes for a zero-nicotine product — but hoping to eliminate that too at some point.

“Vaping is a coping skill,” Galay said. “A kid might be using it excessively due to anxiety.”

His advice to youth? “Think about more options you can do to occupy your time. Just something to keep your mind off of it.”

Galay said that pursuing legal action against JUUL is effective insofar as preventing more injuries and deaths and “if lives are at stake, especially the youth, who are supposed to be the future.”

Roughly 58% of youth who use tobacco products reported simultaneously suffering from severe psychological distress, receiving poor school grades, or experiencing poverty, according to the 2022 National Youth Tobacco Survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

He said schools could be more proactive and use hands-on strategies when preventing students from smoking e-cigarettes.

Ali Hussain, who works at a smoke shop in the Upper West Side, has set strict identification procedures for the shop. A lot of it comes down to his common sense and observing anyone who looks under the age of 30 carefully.

“Step one, we have kept it so far that the children cannot reach,” Hussain said. “Even if they want to buy it from us, first thing is we check the age. If the age is not there, we don’t sell. That’s the bottom line.”

Hussain said he often sees youth as young as 12 or 13 smoking marijuana outside of his shop. A father himself who has never smoked before, Hussain said he trusts his children enough to know the dangers of vaping and smoking, especially because they follow the news.

“Neither cigarettes are safe or vape is safe,” Hussain said. “People are smoking, people are dying.”

New York City passed the Tobacco 21 law, which went into effect in August 2014, prohibiting youth under the age of 21 from purchasing tobacco products and e-cigarettes.

While retailers were required to have licenses to sell cigarettes in New York City, a license to sell e-cigarettes was not required until Aug. 23, 2018.

Hussain passed on scathing judgement on unlicensed smoke shops across New York City that he said will sell vapes and cigarettes from different states, which he said the city, state, and businesses like his, end up taking the hit.

“We are trying to be safe so that we should not get a violation ticket from the city or state,” Hussain said. “Just for precaution purposes, we are playing it safely.”

He feels that the best preventative measures are retailers continuing to check for IDs and school safety agents patting down students and checking backpacks.

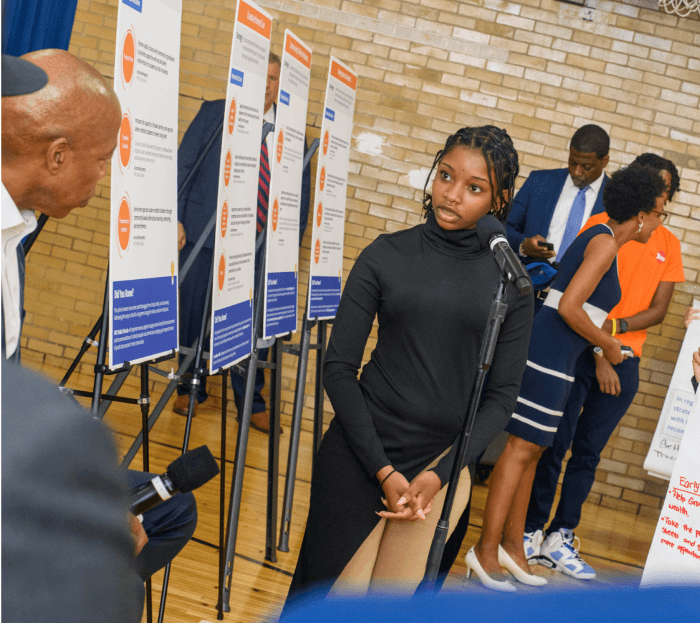

High schoolers: There are other ways to chase the high of vaping

Aayh Ayob and Sam Weinstein, juniors at M479 Beacon High School in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood, said they were both exposed to JUUL as early as middle school. For Weinstein, he first saw JUUL being used by an eighth grader outside of his school.

“I had known people would use it to quit smoking,” Weinstein said. “I knew it had something to do with smoking, so I knew it wasn’t good.”

“I knew it was bad for you,” Ayob said. “We had a very big awareness for it in middle school.”

She said her middle school had once organized an off-campus event encouraging students to disown their vapes.

While youth vaping has declined since 2018 and continued to drop from 2020 to 2021, there are still factors driving underage usage today. One in seven high schoolers and more than 3% of middle schoolers reported having used e-cigarettes recently, according to a survey published in October 2022 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Ayob pointed to peer pressure as a huge factor in youth continuing to vape.

“Especially in this day and age and with teenagers, it’s easy to get addicted to things and be dependent on it,” Ayob said.

While Weinstein said that he’s heard vaping could curb cigarette use, he pushed back on the idea that vaping is used solely as a way to quit.

“I feel like they were using it as the gateway instead of cutting it off,” Weinstein said.

“I feel like people also turn to worse things, like marijuana,” Ayob added.

They acknowledged their school’s efforts to curb on-campus smoking, which included shutting down bathrooms during certain times of the day to prevent students from smoking inside. While this could cause slight inconveniences for students who don’t smoke, both Ayob and Weinstein understood their school’s intention to “spread awareness about it, which is really good and makes people try to recognize there’s a reason why they’re doing that,” Weinstein added.

Weinstein and Ayob liked the idea of a lawsuit holding JUUL accountable in influencing and manipulating youth in their advertisements. Weinstein said he has noticed JUUL’s messaging had influenced youth to believe that “it tastes good apparently.” Ayob said in this case, any action to curb youth vaping is better than no action at all.

The settlement: Severe restrictions placed on JUUL

The settlement requires JUUL to undergo severe restrictions on its marketing and sales practices, including refraining from directly or indirectly targeting youth, limiting the amount of retail and online purchases, not portraying anyone under the age of 35 on its promotional materials, and taking measures to secure products behind store counters and verifying the ages of people who want to purchase JUUL products.

JUUL is also required to perform regular retail compliance checks at 5% of New York’s retail stores that sell JUUL products for at least four years, and invest $5 million to contribute documents to a “document depository” that inform the public about how JUUL created a public health crisis, according to the settlement.

The state will use a “vast majority” of the $112.7 million to fund government agencies, educational organizations, and community- and school-based anti-vaping programs that work to prevent youth vaping and help young New Yorkers who are struggling to quit, according to Attorney General James.

While James said the state isn’t aware of any specific efforts targeting any particular community of color, youth, as a whole, were the targets.

A JUUL spokesperson told amNewYork Metro in a statement that the company is nearing total resolution of the company’s historical legal challenges with the completion of the recent multi-state settlement. JUUL has now settled with 47 states and territories, providing more than $1 billion, in addition to its global resolution of the U.S. private litigation, the JUUL spokesperson stated.

“The company admitted no wrongdoing as part of the settlement, and we suspended all mass marketing of our product in 2019,” said the JUUL spokesperson. “Now we are positioned to dedicate even greater focus on our path forward to maximize the value and impact of our product technology and scientific foundation. Our priorities remain to secure authorization of our PMTAs based on the science and lead the category with innovation to accelerate our mission and advance tobacco harm reduction.”

Thomas Carr, national director of public policy at the American Lung Association (ALA), said the organization noticed an “incredible rise in youth vaping” when JUUL was the main product in the market.

The ALA has been involved with public policy and education to reduce youth vaping across the nation. Carr commented on JUUL’s attempts to directly engage with at least one high school in New York City.

“They tried to deploy youth education programs about vaping,” Carr said. “When a tobacco company or an e-cigarette company does that, you should always be suspicious.”

Carr said there are sale laws preventing underage purchases in place across the country, but that only some stores have complied with these laws. While he noticed that JUUL’s market share has been declining “pretty precipitously lately” and other e-cigarette companies and products taking JUUL’s place, Carr said the lawsuit served its purpose.

“It’s trying to hold JUUL accountable for what they did, rather than necessarily affecting what’s been happening in the present with the e-cigarette market,” Carr said.

He said the ALA has now trained their sights on ending the sale of flavored tobacco products in states and communities, and pointed to Governor Kathy Hochul’s efforts to include this in the New York State budget. If it passes, New York would be the third state to ban flavored tobacco products.

New York City law currently allows sales of unflavored or tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes or e-liquids. All other flavors are illegal, since July 2020.

But what still remains after the lawsuits have been settled and the policies changed could very well be the hardest to fix.

“There’s a lot of youth addiction out there,” Carr said. “We’re struggling to figure out how to help them.”