Last spring, the COVID-19 pandemic pushed our country to the brink. Hospitals struggled as they ran out of ventilators, beds, masks, and countless other critical supplies. Doctors and nurses worked tirelessly for days on end, putting themselves at risk to save others. Hundreds of thousands of our neighbors lost their lives.

Through it all, however, the impacts of COVID-19 have been exacerbated by an epidemic that’s been making our country sicker for generations: obesity.

The data is clear that Americans living with obesity face an even greater risk during the COVID-19 pandemic—and that they are more likely to be people of color. More than three quarters of Americans who were hospitalized for COVID-19, needed a ventilator, or died from COVID-19 were more vulnerable because of their obesity or obesity-related diseases, such as type 2 diabetes. Nationwide, nearly 50 percent of Black adults and 45 percent of Hispanic adults suffer from obesity, compared to 42 percent of White adults.

Shockingly, if the prevalence of obesity had been reduced by just one quarter, the COVID-19 mortality rate would have fallen by 11.4 percent—many of them people of color. As we continue to battle COVID, we must prepare for the next health crisis, and our leaders in Congress can help by passing the Treat and Reduce Obesity Act (HR1577), giving healthcare providers tools to finally treat obesity.

As community doctors serving low-income, immigrant communities of color across New York City, we have seen the impact of obesity firsthand—before and during the COVID-19 pandemic—and we can say without a doubt that it is a disease that requires medical treatment. Pre-COVID, obesity was connected to an estimated 300,000 deaths per year, the second leading cause of death in the country, according to the National Institutes of Health. And there’s more. Higher rates of obesity also means higher rates of high blood pressure, osteoarthritis, and even mental illness – among a laundry list of other chronic health conditions – all of which contribute to skyrocketing healthcare costs. You don’t have to take my word for it, though. In 1997, the World Health Organization recognized obesity as a disease, and, in 2013, the American Medical Association followed suit.

The United States government, however, has not gotten the memo.

While the FDA has approved anti-obesity medications that have strong track records of helping patients battle obesity, Medicare Part D continues to stigmatize obesity—treating the condition as a choice, not a disease. Due to that stigma, these FDA-approved anti-obesity medications are among the short list of drugs excluded from Medicare Part D coverage, lumped in with cosmetic treatments for conditions like hair loss and over-the-counter medications such as cold and flu treatments. Worse still, the program places onerous restrictions on the behavioral therapy used to treat obesity.

Treating obesity is, without a doubt, an issue of health equity for underserved communities, and the need to address it is only accelerating: between 1987 and 2002, the rate of obesity among Medicare beneficiaries doubled. By 2016, it had nearly doubled again.

Here’s how our elected officials in Washington, D.C. can step up and fight obesity. First, we must change the culture and language that exists around obesity and recognize it as a medical condition—not a choice, cosmetic problem, nor a personal failure. Then we must begin to actually treat this chronic disease. The Treat and Reduce Obesity Act will both designate obesity as a known medical condition and provide patients with the medication and therapies they need.

According to research published by the Mayo Clinic in July 2020, nearly half of US adults are projected to be obese by 2030. Investing in obesity treatment today would pay dividends tomorrow by lessening the risk of chronic illnesses and other dangerous diseases for millions of people. This includes Type 2 diabetes—90 percent of people with this disease are overweight or obese—and cancer, 13 types of which have a link to obesity. Overall, reducing the risk of these conditions would save taxpayers nearly $25 million over the next decade.

The pandemic has shown the nation how important preventative care is, especially for the low-income, immigrant communities of color that we treat and that have been hardest hit by COVID-19. SOMOS Community Care’s proven community-first healthcare model shows that when we invest in these preventative measures, we can change lives—but we need support from our elected leaders. It’s critical that Congress pass the Treat and Reduce Obesity Act and give us the tools we need to care for our patients.

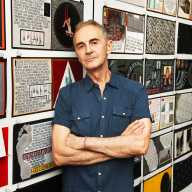

Dr. Ramon Tallaj is the Co-Founder and Chair of SOMOS Community Care and Dr. Henry Chen is the President of SOMOS Community Care.