BY ALEJANDRA O’CONNELL-DOMENECH AND ANGÉLICA ACEVEDO

Queens emerged as the “epicenter of the epicenter” as New York City struggles to contain the COVID-19 crisis — and the lack of available hospital space has undoubtedly added to the strain.

The “World’s Borough” has only 13 hospitals, which accounts for 3,961 beds for its population of more than 2.3 million residents — compared to Manhattan’s 19 hospitals, accounting for 7,642 beds for its population of 1.6 million.

Over the past 15 years, more and more hospitals have been disappearing in Queens, and across the city.

In this timeframe, 10 hospitals in Queens have shut its doors. Those hospitals include Parkway Hospital in Forest Hills which closed in 2008, and St. John’s Queens Hospital, formerly located at 90-02 Queens Blvd., Mary Immaculate Hospital in Jamaica which closed in 2009.

Although those are notable cases of shuttered hospitals, they were far from the only ones that closed their doors.

St. Joseph’s Hospital in Flushing closed in 2005; St. Joseph’s Hospital in Far Rockaway closed in 2007; Peninsula Hospital in Far Rockaway closed in 2012; and Holliswood Hospital and Terrace Heights Hospital, both located in the Hollis neighborhood, then closed in 2013.

Why have so many hospitals closed?

Dr. Joseph Masci, chairman of the Department of Global Health at Elmhurst Hospital — the first hospital in New York City to go overflow with COVID-19 patients — said that this is a result of a nationwide trend.

“Hospitals in the United States, including in New York, are designed not to have a lot of extra empty beds,” Dr. Masci said during a virtual town hall on March 30. “They’re kept pretty full, all the time. So when a new disease comes into the picture like this, and it affects people so that many of them would require hospitalization, it creates a logistical problem for hospitals.”

In order to contain the pandemic, the city that never sleeps has gone on pause for a to-be-determined time period.

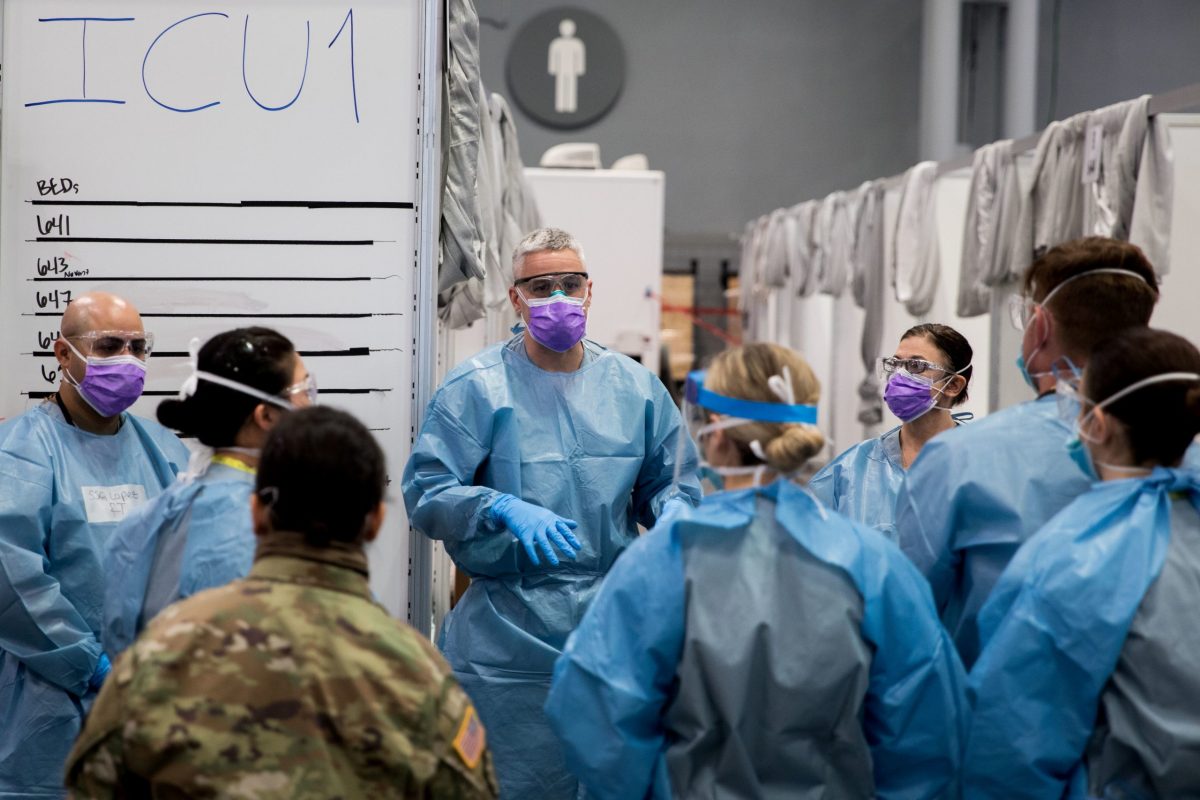

City, state and federal governments have also worked to create temporary hospitals across the region. The Jacob Javits Convention Center in Manhattan has four military hospitals and a temporary hospital which will serve up to 2,000 patients. Docked not too far from there is the USNS Comfort, a naval hospital ship serving up to 500 individuals that this week was finally allowed to accept COVID-19 patients.

Temporary hospitals are also due to be established at Aqueduct Racetrack in Queens, the Brooklyn Cruise Terminal and the New York Expo Center in the Bronx. These will provide another 4,000 beds.

Once the coronavirus crisis abates, these temporary hospitals will go away. But the pandemic should force the city to re-evaluate its position on preparation for the next outbreak, according to City Councilman Mark Levine, who chairs the City Council Health Committee.

“Much like 9/11, this is going to cause us to reconsider everything in terms of how we prepare for emergencies,” Levine told am New York Metro. “In retrospect, it is clear that it was a mistake to reduce hospitals, and it was certainly a mistake to not have more supplies stockpiled. But that is a collective, societal failure that all of us are accountable for.”

Dr. Jill Kalman, director of Manhattan’s Lenox Hill Hospital, agrees that preparation is key to dealing with any health crisis.

The city, state and federal governments, she suggested, should coordinate with health executives to cement a plan for when another pandemic, or equally life-changing incident happens next in the city, to figure out a contingency plan. Because even if more hospitals were to be built in the city, staffing and protocols would still need to be worked out.

Hospitals should understand what their maximum capacity is and how to quickly make room for an influx of patients before disaster strikes, Kalman noted. There must also be developed plans on how to quickly procure essential medical supplies like gowns, masks and gloves for healthcare workers and ventilators for patients.

“Why don’t we know those companies now that could be able to produce instantly is the wrong word but as quickly as possible to get the right amount of supplies to the hospitals when they need it?”said Dr. Kalman.

City hospitals should also focus on making sure to prioritize load balance, which is something Kalman touted about Northwell Health’s 23-hospital system.

“We look across our entire healthcare system and if our Queens hospitals are, which they have been, have really been challenged with high volumes and high acuity,” she said, “we take transfers from the hospitals to alleviate the stress in their ICU’s and their emergency department which is considered load balancing in a system.”

The state Health Department mandated something similar in recent weeks, ordering all hospitals across New York to work together on balancing the patient load and ensuring ample supplies and staff to treat the sick.

With additional reporting by Benjamin Mandile and Robert Pozarycki