BY BOB KRASNER

It’s impossible to underestimate the power of music and its ability to entertain, shock, unify and empower — and in the case of vibraphonist Chris Dingman, to make one of life’s most difficult challenges a little easier to deal with.

Dingman was “drawn to music from zero,” he claims. He eventually started piano at age 9, inspired by his mom, who played ragtime. He moved from piano to drums, playing in an eclectic series of bands in high school that took him through ska, heavy metal and jazz.

It was at Wesleyan University that he encountered a professor named Jay Hoggard, an esteemed jazz musician who had this conversation with Dingman:

Hoggard: “You play vibes?”

Dingman: “No.”

Hoggard: “You’re going to play vibes.”

And so he did, and he did it well enough that after graduating he was accepted into the esteemed Thelonious Monk Institute in Los Angeles and found himself studying with jazz legends Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter and Ron Carter, among others.

Not only did he study with them, Dingman actually toured with Hancock and Shorter. One can’t really exaggerate what a singular opportunity this was.

“I was young and still learning,” Dingman recalls of that tour. “They were a real inspiration.”

“The most important thing about Herbie and Wayne is that they are advocates of people discovering who they are, of finding their own voice,” he continues. “Herbie would sit down and narrate his inner thoughts for us while he was playing. It was a soul searching process.”

Aiding Dingman in the process was his discovery of the Vipassana method of meditation, which he continues to employ up to two hours a day when possible.

The early 2000s found Dingman in New York City, playing experimental jazz in venues such as the Knitting Factory, CBGB’s and Niagara while working as a temp at a hedge fund. That lasted a year before he began his career teaching piano and drums, which he continues to do today. He also teaches vibraphone performance at The New School in Greenwich Village.

In 2011, he put out the first of three CDs of his own compositions recorded with a small group.

Fast forward to a few years ago, when his mom was in the hospital but didn’t want any visitors. Instead of a get well card, Dingman recorded two tracks of solo vibraphone music and sent it to her. The music was much appreciated and apparently quite helpful, as she soon went home.

His dad, however, was next. Joe Dingman hadn’t been feeling well for awhile and was finally diagnosed with a rare, terminal heart disease. While in the hospital, he became very agitated but was soothed by the music that had originally been created for his wife.

“Hospitals care for the physical needs but not the emotional ones,” notes Chris Dingman.

Unfortunately, his father’s next stop was a hospice, as his condition worsened. Dingman recorded more music for his dad, which was played constantly at his bedside. His condition improved enough that it was no longer appropriate for him to be at the hospice, but the family knew that it was just a matter of time.

Dingman’s father was brought back to his Lancaster, PA home where he would spend his final two months. Not content to record his musical missives remotely, Dingman packed up his instrument and brought it to his father’s bedside. Over several weekends he played the vibes, creating long beautiful improvised pieces that were recorded as his dad lay in bed listening.

“He would wake up in panic in the middle of the night, sometimes getting very agitated and couldn’t breathe. The music calmed him down,” explains Dingman. “And during the day, it excited him. Dad named all the tracks, starting with the first, ‘Healing Love.’ He was really excited to share the music. It reached him on a deep level and he wanted others to experience it.”

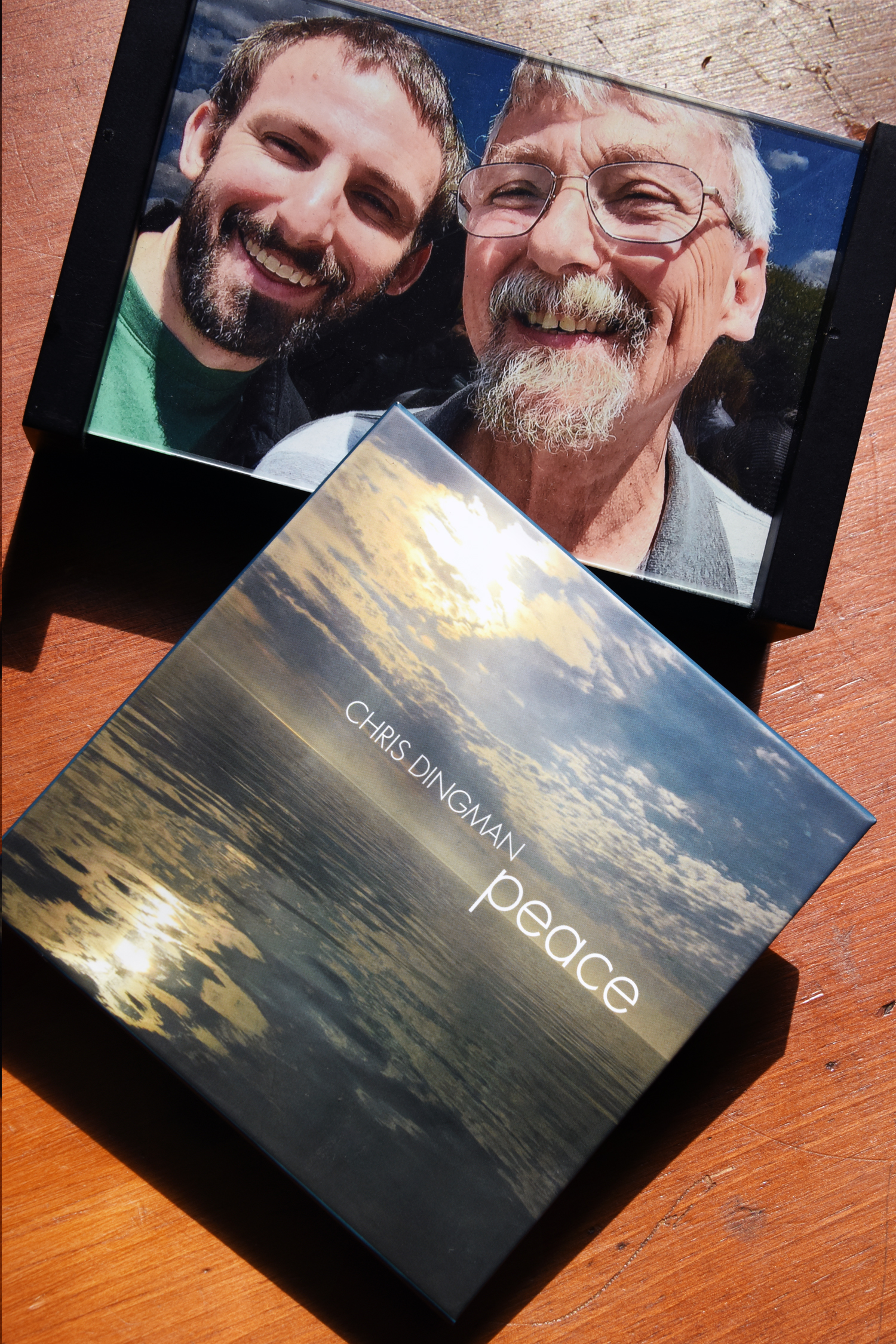

Dingman has made sure that his father’s wish has come true, in the form of a five-hour box of music entitled “Peace.” All of the music that was recorded is there, after the artist spent a year mixing it and cleaning it up.

“It was built into my grieving process,” he says. The result is a gorgeous soundscape that Brian Eno would probably appreciate, but has an emotional core that is sometimes missing from the ambient music genre.

“It’s a soothing balm,” muses Dingman. “It takes you someplace else. It’s not circular, it moves you forward. … While I was playing, I tuned into the moment. I sometimes go into a meditative, trance state where I’ll see faces.”

When asked how this music compares to his composed pieces, he mentions that the improvisations are “like having a conversation, as opposed to working from a script.”

Chris recalled what his father Joe had told him nine days before his passing: ““A miracle has happened through this music. It has transformed me over and over again. It has made me stronger, made me want to live life again.” Joe Dingman died peacefully during the night, while the track “Sky” was playing.

Chris Dingman’s music can be explored at chrisdingman.bandcamp.com and more info about the artist can be found at chrisdingman.com.