The promise of a “normal” U.S. economy this summer, which kicked off with the June revival of restaurants, air travel and baseball games, is transforming into an uncertain fall of rising health and economic risks.

Labor Day weekend, the traditional end of the U.S. summer season, was pegged as the moment when the economy would finally transition out of the pandemic slump, with private sector jobs and wages replacing unemployment benefits.

Instead, the summer is closing with rising COVID-19 case counts, hospitals bulging with patients and dark predictions. The University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation projects that between now and Dec. 1 there will be 100,000 COVID deaths, more than in the same period last year, when a wave of winter infections took hold and vaccines were not yet available.

“I don’t think fall 2021 is going to give us the catharsis we were waiting for,” said Nick Bunker, economic research director for hiring site Indeed, or provide a clear view of how fast U.S. job markets can recover the 5.7 million jobs missing from before the pandemic. “The transition is going to be longer than expected. The issue is, is it a stumble or does the baton get dropped?”

Special $300-per-week unemployment benefits end on Saturday. While employers hope that will usher new job applicants into a labor-starved market, there are signs the pandemic may have begun to curb their hiring plans instead.

The reopening of schools, far from smoothing the way for parents to return to full-time jobs, has been marked by erratic outbreaks, quarantines and closures, as school boards battle over masking students.

The manager at The Irish Whisper, a pub near the Gaylord National Resort and Convention Center in Oxon Hill, Maryland, said that business has fallen off since an initial summertime rush.

“It’s not as great as pre-COVID, but it’s better than not having anything,” said the manager, who only gave his first name Andrew. “I thought we were in the clear and then this variant emerged.”

After a strong start early this summer, attendance is dropping in baseball stadiums.

Biden’s virus overshadowed

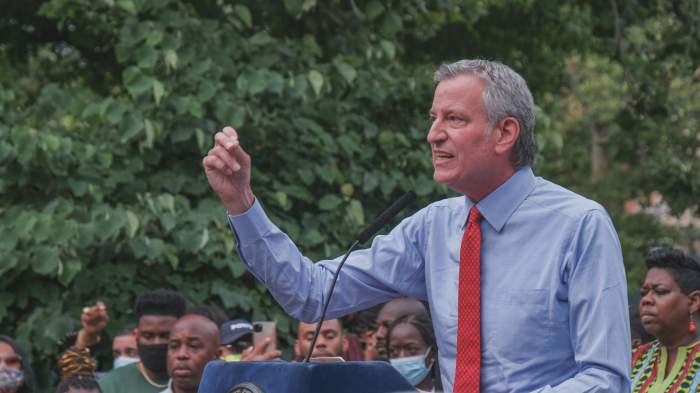

It is a particularly sensitive moment for the Biden administration.

The Democratic president has taken a hit in the polls from the resurgent virus, faces criticism over the Afghanistan withdrawal and must deal with the aftermath of Hurricane Ida and a gauntlet of deadlines in Congress in coming weeks to keep the government funded and his economic agenda on track.

Biden’s strategy of wiping out COVID by getting all of the United States vaccinated was hindered by a politically charged anti-vaccination movement this summer, and the pace of vaccinations has slowed since peaking in April.

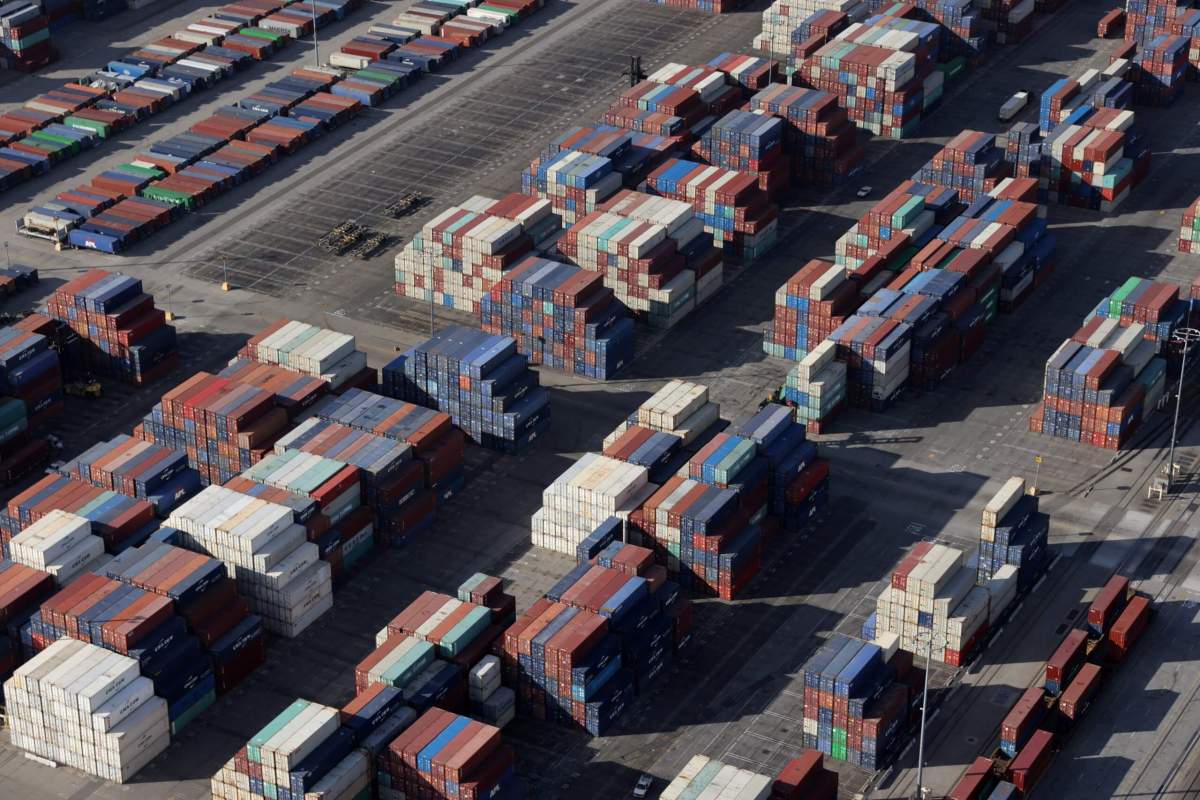

A run of higher-than-expected inflation due to supply chain woes and labor shortages consumed what would otherwise have been healthy wage gains. A closely watched index of consumer confidence, which can influence spending, tumbled in August to a six-month low.

Progress on the virus “is (Biden’s) No. 1 advantage, but people are discouraged and frustrated and it’s also interacting with the economy,” said one Biden adviser not authorized to speak on the record.

Administration officials believe the recovery largely remains on track, and infrastructure and spending plans may partly make up for the lapsed weekly unemployment insurance payments.

Democrats are hoping to finalize a $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill as soon as this month while also working on a $3.5 trillion bill that could only secure party-line support.

Republicans are fighting the administration’s most ambitious spending plans. Goldman Sachs economists now estimate the “fiscal cliff,” as spending rotates away from the record government transfers of the past 18 months, will be a noticeable drag on growth by late 2022.

Oxford Economics economists expect to trim their outlook for 2021 gross domestic product growth to 5.5%, down from 7% in early August.

The reduction reflects “the deteriorating health situation weighing on optimism and spending, lingering capital and labor supply constraints and a slower inventory rebuild,” Oxford chief U.S. economist Gregory Daco said in an email.

Hiring weakness?

Data on August jobs due to be released Friday will show whether the current surge of infections, which drove the number of new cases from around 11,000 a day in mid-June to almost 150,000 daily this week, is slowing hiring or the recovery more broadly.

Economists are not expecting the sort of collapse in demand for restaurants, travel and other services seen in earlier virus waves. Many Federal Reserve officials feel businesses and families have learned to navigate the situation, either finding ways to lower the risk of infection as they resume work and business, or worrying less about infection because they’re vaccinated.

U.S. firms added nearly a million jobs a month in June and July, and consensus forecasts for August project a still-robust 750,000 gain.

Some employers argue that that figure could me much higher, given the record number of openings, if they had not had to compete with unemployment benefits. That hasn’t been borne out in states that ended the federal benefits early over the summer, where there’s little evidence more people went back to work.

Now, employers may be pulling back on hiring themselves.

Hiring at around 50,000 small businesses has fallen since midsummer, data from time manager Homebase shows, while a workforce recovery index from time management firm UKG, which analyzes time card punches, fell 2.4% from July to August.

It was sharpest in the southeast, where the spread of the virus was most intense.