Gov. Kathy Hochul announced Monday that a project that aims to reduce truck traffic on local streets in the South Bronx is nearing completion.

The project, which involves widening the Bruckner Expressway and adding new exit ramps, aims to more efficiently manage the massive number of trucks traveling to and from the Hunts Point Terminal Market, the world’s largest food distribution center.

The announcement celebrated the completion of phase 2 in the $1.7 billion “Hunts Point Access Improvement Project,” which aims to more efficiently manage the massive number of trucks traveling to and from the Hunts Point Terminal Market, the world’s largest food distribution center.

Phase 2 — which Hochul said is being finalized ahead of its scheduled autumn completion date and below its $518 million budget — encompasses the widening of 1.25 miles of the Bruckner Expressway between East 141st Street and Barretto Street and new on-and-off ramps at Leggett Avenue, providing another route for trucks to take from the highway to the produce market.

A third phase, which is under construction, will see the reconstruction of the “bottleneck” Bruckner-Sheridan interchange and complete the addition of a third lane on the Bruckner.

The governor, standing against a green backdrop at the La Central YMCA in the South Bronx, painted the project as a win for the environment, taking trucks off residential streets where they wear down roads and spew toxic fumes, contributing to the Bronx having the city’s highest asthma rates.

“[South Bronxites] live in a community that’s under siege from toxic fumes from heavy truck traffic,” the governor said, referencing the history of environmental racism in the borough’s planning decisions. “Today, we’re gonna take back our community, take back our air and our sidewalks and our streets, and make sure that everyone who calls this wonderful community home will have a better outcome, a better life, because they deserve it.”

The first phase of the project, completed in October, saw the addition of a new two-way ramp between Edgewater Road in the east of Hunts Point to Sheridan Boulevard — which itself was converted from an expressway to a local road in 2019 — plus a ramp from the Bruckner to Edgewater Road.

On Monday, Hochul also announced a $10 million investment in zero-emission school buses and electric vehicle charging stations in the Bronx. As part of its approval for congestion pricing, the MTA previously committed money towards electrifying fossil fuel-spewing refrigeration trucks at Hunts Point and on charging infrastructure for electric trucks.

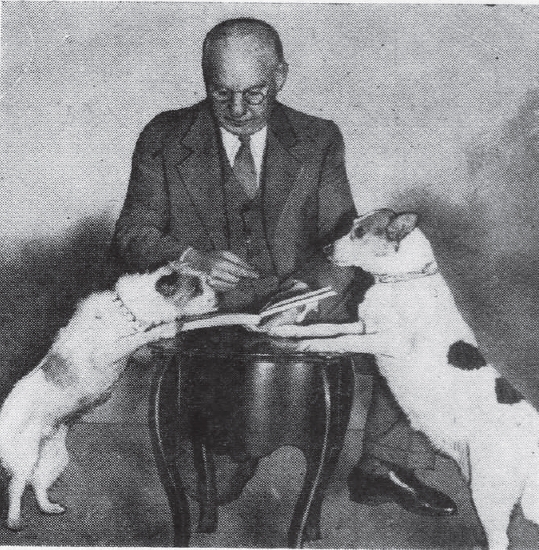

All told, Hochul painted the announcement as a win for Bronxites used to deleterious truck traffic and dirty air. The plan is also “righting the wrongs of the Robert Moses era past,” she said, referring to the “power broker” who for decades held near-dictatorial control on New York’s transportation planning projects, ramming highways through low-income neighborhoods that led to wide-scale displacement and the severing of existing communities.

Moses’ legacy has, of course, been tarnished for decades, as the human cost of his projects—and the degree they entrenched the use of the automobile— have become clearer.

The Bruckner was one of the final urban highway projects Moses completed; he intended for it to extend further north along the Sheridan Expressway but was halted by extensive community opposition. Sheridan Boulevard stops at the Cross Bronx Expressway, which was perhaps Moses’ most controversial project, responsible for the displacement of tens of thousands of Bronxites and the destruction of entire communities.

Decades of research has suggested widening highways does not reduce traffic congestion and may in fact make it worse, through a phenomenon called “induced demand.” Some cities, like Baltimore and Buffalo, are looking to use federal infrastructure money to tear down or cover up urban highways that divided communities; New York City is seeking nearly $1 billion in infrastructure funds to “reimagine” the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

Earlier this month, City Comptroller Brad Lander released an audit criticizing the state for spending too much infrastructure money on expanding highways, singling out the widening of the Van Wyck Expressway in Queens.

Being the busiest food hub on Earth, nearly 80,000 trucks travel to and from the Hunts Point peninsula each day to access the market. Hochul said that about 13,000 of those travel on residential side streets, belching carbon into the air and making the streets dangerous for locals; her office says the new ramp to Leggett Avenue will redirect trucks to use one main route and not side streets.

But Nilka Martell, founder of local nonprofit Loving The Bronx and a speaker at the announcement, noted that when Leggett Avenue becomes Randall Avenue closer to the market, it passes right through a residential area, albeit on a commercial street.

“You’re really just diverting the traffic and you’re still putting them into a semi-residential area. It does lead to the industrial area, but it is crossing at least a couple of blocks of residential area,” Martell told amNewYork Metro. “I think that all of these projects really come down to what’s feasible.”

In a series of planning sessions, many residents, including Martell, had significant objections to the plans, particularly the ramp at Edgewater Road adjacent to Garrison and Concrete Plant parks.

Locals preferred an exit further south at Oak Point Boulevard, which would keep truck traffic entirely confined to the neighborhood’s industrial sectors. But state transportation officials deemed that route infeasible: it would require building a ramp atop the Oak Point rail yard and ostensibly reduce the yard’s train capacity, which was deemed a nonstarter by Amtrak and CSX, the railroads using the yard.

A spokesperson for state DOT told amNewYork Metro that the Oak Point ramp would involve considerably more expensive property acquisition, costing hundreds of millions of dollars more and taking years longer than the Edgewater ramp, while reducing railroad capacity by putting structural supports on the yard’s property.

Martell is optimistic that the project could, in the end, reduce truck traffic and pollution in Hunts Points and, in fact, take some steam out of Moses’ legacy. That legacy could be torn down further, she says, if the city ultimately decides to cover up the Cross-Bronx, for which the feds have funded a feasibility study.

But Bronxites have seen many politicians make big promises and fail to deliver through the years, so Martell says community members will independently monitor air quality in the area to keep track of the progress, or lack thereof.

“All we can do is wait and see what the impacts of these projects are,” said Martell. “We’ll see years from now if indeed the pollution has gone down. And if not, we go back to the drawing board and we put pressure on the state to look at this project again and see where we went wrong.”