BY Ann Choi, Christine Chung, Clifford Michel and Greg B. Smith, THE CITY

This story was first published by THE CITY on Oct. 28.

Seven years after Superstorm Sandy deluged New York City, more than eight out of 10 properties in coastal areas the federal government deems extremely vulnerable to the next disaster are without flood insurance, an investigation by THE CITY found.

Meanwhile, the number of flood insurance policies protecting New Yorkers has dropped markedly since the end of 2013 in two of the boroughs hardest hit by the storm: Staten Island, which saw an 18% decline, and Queens, which experienced an 8% decrease.

Residents of roughly 250,000 houses and apartments within red-flagged flood zones are left exposed — thanks to the high cost of insurance policies and a protracted disagreement between local and federal officials.

City and Washington bureaucrats are at least five years away from forging a common set of flood maps that will determine who must buy insurance — leaving New Yorkers reliant on risk ratings little changed since the 1980s.

Mayor Bill de Blasio is disputing the map the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) created in 2015, which significantly expanded areas identified for high risk of flooding, based on Sandy’s path of destruction.

So for now, only property owners with federally backed mortgages who are living within the old, pre-Sandy zone — last updated by FEMA in 2007 — are required to purchase flood insurance.

Homeowners end up mired in confusion over seemingly contradictory rules: In some cases, people whose properties were devastated by Sandy are living without flood insurance while new or rebuilt homes next door must be made floodproof.

As it all gets sorted out, many homeowners are rolling the dice — skipping often-pricey flood insurance and praying another storm doesn’t send the waters of New York Harbor, Jamaica Bay or Buttermilk Channel barrelling into their living rooms.

“I know the danger. Trust me, I know,” said Semyon Krugolets, 66, a retired cabinet maker whose Staten Island home took on two feet of water during Sandy. “But sometimes you have to make these decisions.”

THE CITY’s investigation, tackled in the weeks before the Oct. 29 anniversary of Sandy making landfall in New York, found:

• Citywide, about 51,000 out of the 313,000 homes located within both the old 2007 map and the proposed 2015 lines carry flood insurance. That represents 16% of the properties.

• Some high-risk neighborhoods are far better protected than others. Half of homeowners in sections of Howard Beach, Queens, have insurance — versus just 14% of property owners in similarly vulnerable areas of Canarsie, Brooklyn.

• The number of flood insurance policies citywide has dropped by 2% since 2013 — exposing sharp differences between the boroughs. Insurance coverage plummeted in Staten Island and Queens, while Manhattan logged a 27% increase. Brooklyn, which was slammed by the superstorm, recorded a 2% decrease. The Bronx, which was barely touched by Sandy, experienced a 4% dip.

CLOSED-DOOR NEGOTIATIONS

A year after the flood, FEMA produced its first post-Sandy flood zone map, which it updated in 2015.

That map greatly expanded the area FEMA said would likely flood if another storm hit tomorrow — and where everyone with a mortgage backed by the federal government would have to get flood insurance.

The stakes are high for homeowners in the newly flagged areas with government-backed mortgages. If FEMA’s lines hold, homeowners would have to purchase insurance that could cost thousands annually — or could be ineligible for future FEMA aid if they received disaster assistance after Sandy.

De Blasio contested that map — arguing it was based on erroneous assumptions about high tides and didn’t properly factor in non-tropical storms in calculating flood scenarios.

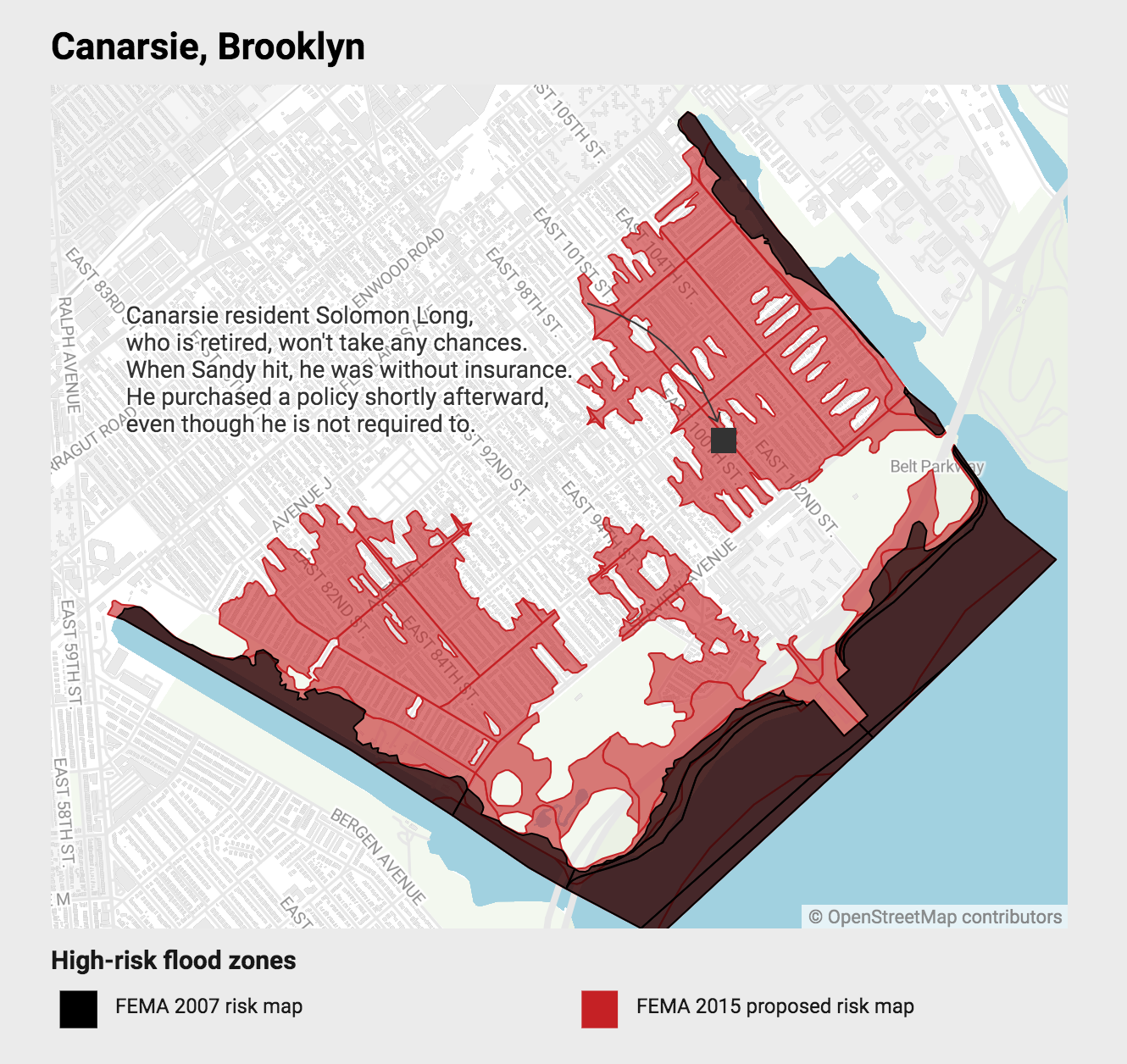

The mayor also argued that in some neighborhoods, the prohibitive cost of flood insurance would devastate thousands of working-class homeowners FEMA moved into a flood zone. A prime example: Canarsie, where no homes were within the 2007 map but roughly 10,000 fall into the 2015 version.

In October 2016, FEMA agreed to review its map. Both sides have been working on a compromise since.

The effort is taking place largely behind closed doors with little public explanation about how it’s going and exactly when there will be an official declaration about who has to buy flood insurance — and who doesn’t.

Earlier this month, three years after both sides first started talking, FEMA presented City Hall with its first “Intermediate Data Submittal.” This draft report — which has yet to be made public — did not propose a new map, but instead simply informed City Hall about what methodology and data FEMA would use in crafting a new map.

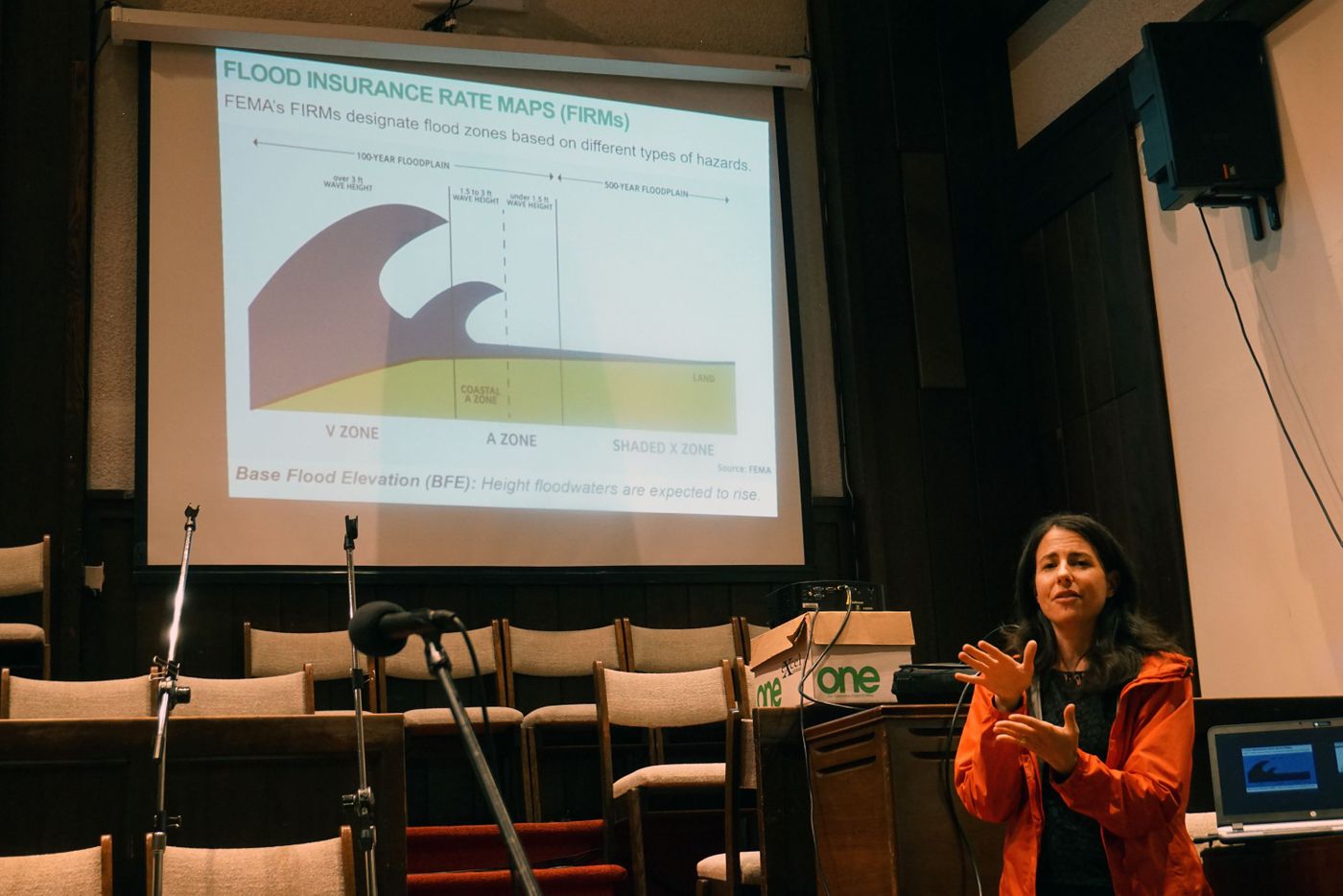

At a recent public meeting discussing flood insurance requirements in Coney Island, Dana Kochnower of the Mayor’s Office of Recovery & Resiliency told the audience a new flood zone map is expected to be released by 2022.

But according to FEMA, a final map won’t be revealed until 2024.

And Kochnower conceded, “We could wind up right back where we were but at least we would know that it is based on more precise data and analysis.”

‘IT TAKES A LONG TIME’

Meanwhile, the dance between the city and FEMA is slogging ahead. A “storm surge and wave conditions re-analysis” isn’t due until 2021. A “wave hazard analysis” and draft flood plain maps won’t be complete until 2022. Preliminary maps will be unveiled in 2023, followed by a public comment period.

“It takes a long time to do this stuff,” said FEMA’s Michael Foley, acting risk analysis branch chief for Region II, which includes New York. “It’ll be a better product for the public to truly understand the hazards that they face.”

But City Hall, which started the process with its appeal of the 2015 map, complains FEMA is taking too long.

“We’ve been using maps that are often dated in determining what these flood insurance rates are in vulnerable areas,” said Jainey Bavishi, director of the Mayor’s Office of Recovery & Resiliency. “We need FEMA to move faster on updating these maps in general.”

Bavishi said the administration has “been really pushing FEMA as much as possible. We’ve been at the table doing independent technological review to validate the work that they’re doing to make sure the work is scientifically valid.”

CONFUSION OVER WHO PAYS

Even while pushing back on FEMA’s 2015 maps, City Hall is relying on them to decide where any new construction or “substantial renovation” must be floodproofed under the building code.

Bavishi said the administration took this position “because we are building as resiliently as possible. All new construction and substantial rehab is required to account for this most recent map in construction of their building.”

A lot of new construction and substantial renovations have taken place within FEMA’s 2015 zone — more than 8,300 permits for this kind of work were issued in the last four years, city Buildings Department records show.

Property owners who live outside the 2007 zone, but within the new neighborhoods added in the 2015 version don’t have to get flood insurance. Still, city personnel working on resilience efforts encourage them to buy policies.

“The city thinks it’s extremely beneficial for property owners to maintain their flood coverage on an annual basis,” Bavishi said, referencing the Center for New York City Neighborhoods’ “Floodhelp” website, which lets homeowners see whether they’re located within flood zones and provides information on how to get insurance.

Foley of FEMA also urges homeowners in the 2015 zone to take out policies, particularly now. It’s cheaper because — for the moment — the area is not technically a flood zone.

“They’ll get a lower-cost policy,” he said. “They probably are in an area that could be flooded, so you’re probably better off to get flood insurance.”

‘I WOULDN’T TAKE A CHANCE’

The vulnerability issue is particularly acute in Canarsie, a working-class neighborhood at the far end of southeast Brooklyn, perched on Jamaica Bay.

There, thousands of households benefited from FEMA aid after Sandy — making their properties potentially ineligible for post-disaster financial assistance if they remain uninsured.

No properties in Canarsie fell within the 2007 FEMA flood zone before Sandy, but about half the units are covered by the 2015 updated map.

When Sandy hit, many suffered storm damage. But thanks to de Blasio’s challenge to FEMA, Canarsie residents were not required to purchase flood insurance.

Since Sandy, the number of flood insurance policies in Canarsie have shot up sixfold, to roughly 1,400. But that’s still only about 14% of all housing units considered high-risk under the proposed 2015 map.

Solomon Long, a retired school administrator, didn’t have flood insurance when four feet of water inundated his basement and garage. After Sandy, he got it.

“If you had seen the damage, and if I had to pull that out of my pocket, that would be a financial burden. So I wouldn’t take a chance,” he said.

Long pays $300 a year. That’s because he lives in an area that’s included in the 2015 map, but is not an official a high-risk zone amid FEMA’s ongoing talks with City Hall. The median annual flood insurance premium for homeowners in high-risk zones was $3,000 in 2016, officials say.

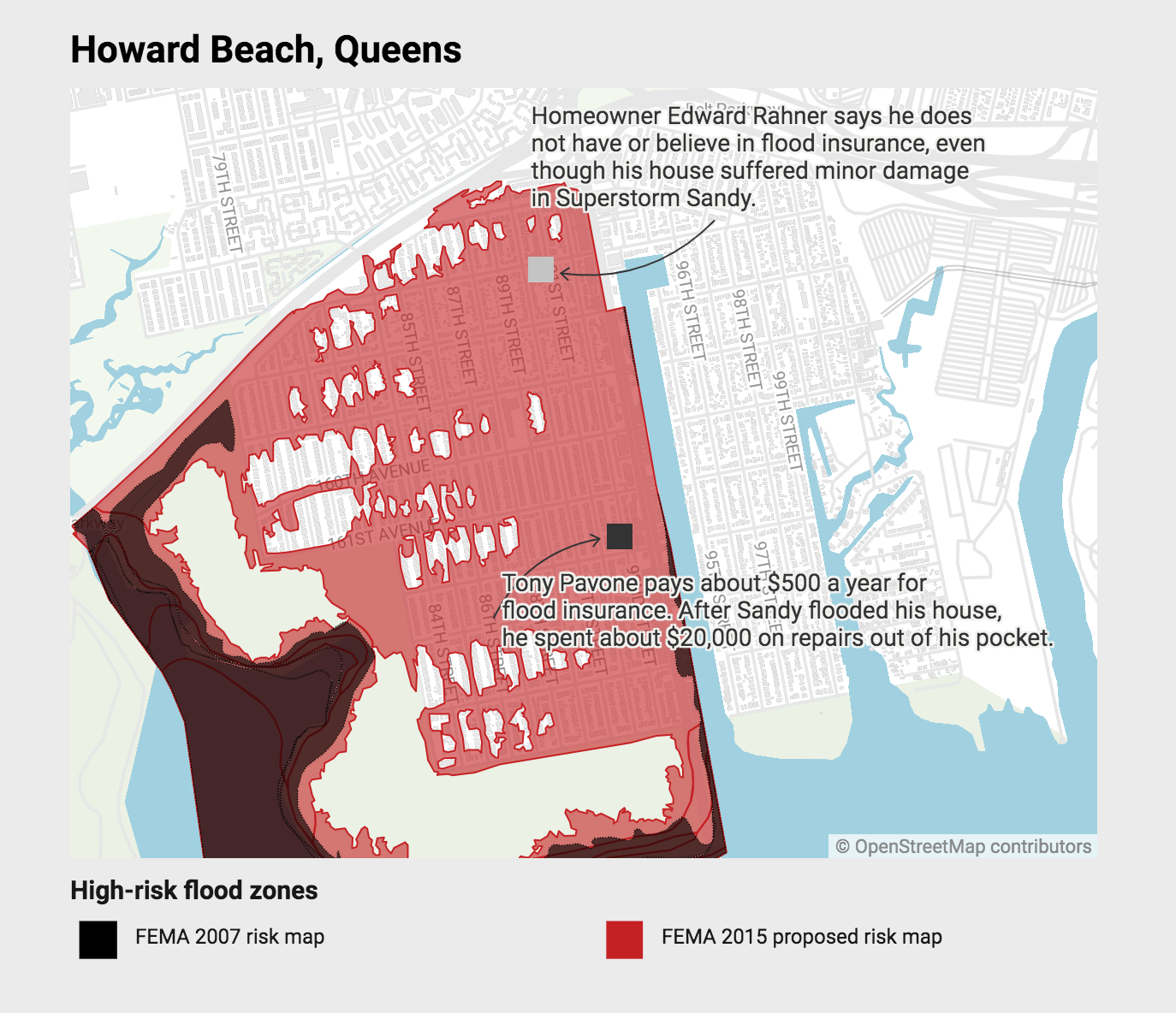

A few miles east along the Belt Parkway, Howard Beach, a quasi-suburban enclave of tidy one-family homes with snug lawns, also went from outside to inside the flood zone after Sandy.

A homeowner there named Nick, who didn’t want his last name used, does not have flood insurance, even though his home was badly damaged seven years ago. His rationale is that storms like Sandy “happen once in 100 years, so I wasn’t about to spend that kind of money.”

‘WHERE YOU GONNA GO?’

Howard Beach homeowner Tony Pavone, 74, bought flood insurance six months after Sandy wreaked about $70,000 worth of damage on his house — including three feet of water in his first floor, where he had a bar and a sauna.

He estimated FEMA paid for $20,000 of his repairs, and he coughed up the rest.

“It was terrible,” he recalled. “Water all over, no heat, no electricity for three weeks. You couldn’t drive a car because there was no gas. Where you gonna go?”

Pavone said he got a discount on flood insurance after Sandy and now pays only $500 a year. Asked if he feels safer having the insurance, he replied, “At least it will cost much less, but no, not safer.”

Another Howard Beach homeowner, Edward Rahner, 67, refuses to get insurance even after his basement flooded during Sandy, because he’s skeptical he’ll get paid his due if his home suffers damage.

“I heard many people didn’t get their money yet,” he says of neighbors who filed claims after Sandy.

Declining insurance coverage in Staten Island has left about two-thirds of the housing units in high-risk zones exposed.

Rep. Max Rose (D-Staten Island, Brooklyn) said in an interview with THE CITY that Congress has let the National Flood Insurance Program become unaffordable.

The law allows the program to increase premiums by as much as 18% annually. A policy can easily double in price within six years.

“With the wages of the middle class stagnated all while education costs and health care costs skyrocket well past the rate of inflation people have to figure out how to make ends meet,” Rose said.

“And one way they’re doing that is they’re not going to be opting into their flood insurance plans anymore,” he added. “They’re going to take that risk. And that is wrong, it is bad and it’s completely our fault that they’re doing this.”

That’s the case even in neighborhoods like South Beach that were all but wiped out when Sandy’s storm surge washed ashore. THE CITY’s analysis estimated the number of policies dropped 6% in high-risk flood zone Staten Island neighborhoods post-Sandy.

‘I CAN’T PAY ALL THAT’

Homeowners who have already paid off their mortgage aren’t required to get flood insurance. Many don’t bother.

Retired cabinet maker Semyon Krugolets, who owns his home outright, says he got insurance after the storm damaged his first floor and garage. He ditched the policy about a year later, deciding the cost outweighed the benefits.

“I’m worried, but listen: I don’t work,” said Krugolets. “My wife doesn’t work and (flood insurance) is very expensive.”

South Beach homeowner Joseph Papapendra, 68, has paid off his mortgage and has no interest in buying flood insurance, even though his home on Liberty Ave. endured extensive damage in the 2012 storm.

“Everytime the Sandy anniversary comes around, I think to myself I might be up s—’s creek, you know?” he said. “But it is what it is. I can’t pay all that.”

His solution is simple: “I’m not gambling anymore. In eight months, we’ll be all packed out and moved out to Georgia and I won’t have to worry about flooding.”

This story was originally published by THE CITY, an independent, nonprofit news organization dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.