Imagine this. You’re a young American art curator with great promise, six years on the curatorial staff at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), as well as curating for the Smithsonian amongst other elite institutions.

You are offered the opportunity of a lifetime: curate an international exhibition of modern art with limitless funds at your disposal. The caveat? It’s in Iran. But not the Iran of today whose government has an appalling human rights record, exerts extremist oppression of women and harbors a vitriolic hatred of the America; not the post-Islamic Revolution Iran ruled by the Supreme Leader Sayyid Ali Hosseini Khamenei, dedicated to “Westdeoxification,”and who has totalistic control over Iranian life, culture, law and international relations.

Rather, this is pre-1979 Iran, ruled by the dynasty of Mohammad Reza Shah (Emperor/King) and Shahbanou Fahah Pahlavi (Empress/Queen), who were both trying to advance their nation culturally, economically and in terms of education in active, benevolent ways. Of course there are many modern-day Iranians who share this vision of advancement, freedom from persecution and the liberation of women, but the fight against a fundamentalist regime has always been a tough one—but one that, Stein agrees, should never be abandoned.

While the Shah moved closer to a capitalist model of economics called the White Revolution, building schools, libraries, advancing land reform and focusing on education—under the his reign literacy rates leapt from 17% in 1963 to 50% in 1977—his wife, the Empress, was focused on culture. And given that this was a time of recession in America and Europe while Iran was experiencing its very own gold rush and flush with oil money, the Empress was perfectly positioned to enact her vision of a country with a lively, sophisticated and evolving art scene.

Given the go ahead by her husband to build museums of art in Iran’s capital city, Tehran, and another in Shiraz, the Empress, whom Stein describes as a “discrete feminist”attempting to “quietly fulfill the goal of creating a cultural dialogue between east and west,” began selecting foreign art experts and architects to get her projects underway with a “secret budget,” for works that would later be discovered as bank-rolled by the National Oil Company beginning in 1973.

Of course, one of these head-hunted experts was Donna Stein, whose new memoir “The Empress and I” tells the story of her time working in Iran, curating the museum and her enduring friendship with the Empress after she was exiled.

Although the Iran of this time was not hateful toward the west, Stein had many reasons to be apprehensive of traveling to alone as a foreign woman: she was to travel to a third world country where she did not speak the language, know the customs, know what clothing was appropriate for any given situation and was given not a contract but a “letter of agreement” that her lawyer brother described as, “the most barren legal document [he] had ever seen.” Nevertheless, Stein is adventurous, had already been a world traveller and viewed the position as “a professional stepping stone—and at the very least a life changing experience.” She would end up on this voyage of procurement and curating from 1975-1977.

Astoundingly, an astrologer who only knew where and when she was born read her chart before she left New York and told her she had been a teacher in Persia in a past life. Even for a skeptic, this is a pretty compelling tale.

And so she set off, frequently traveling between Iran and America to apply her expertise in creating an exhibition that would begin with Impressionism right up to modern day, more avant-garde work.

The exhibition was to be a fusion of Persian and Western art whereby each culture could learn from one another and, pointedly, Stein wanted to include a photography section, as photography exhibitions were not common in Iran and considered an “intellectual risk.” Her superiors eventually relented to her tenacity and a room was dedicated to photography.

When amNewYork Metro asked Stein why they thought she was selected she mentioned her credentials but also emphasized that there were many foreigners being invited to help in the country’s modernization, from farming to architecture, and Iran was doing this because they simply lacked the knowledge of how to change their society for the better at a rapid pace.

She writes, “Iran needed someone to evaluate works from an art historical perspective……[offering] me a golden opportunity to adapt my knowledge and curatorial skills to an ancient culture while scouring the universe for masterworks irrespective of cost!”

And so Stein got to work. She was never involved in the monetary side of the purchases, but on the subject of dollars, the art that she procured for $25 million is estimated to be worth around $3 billion on today’s markets.

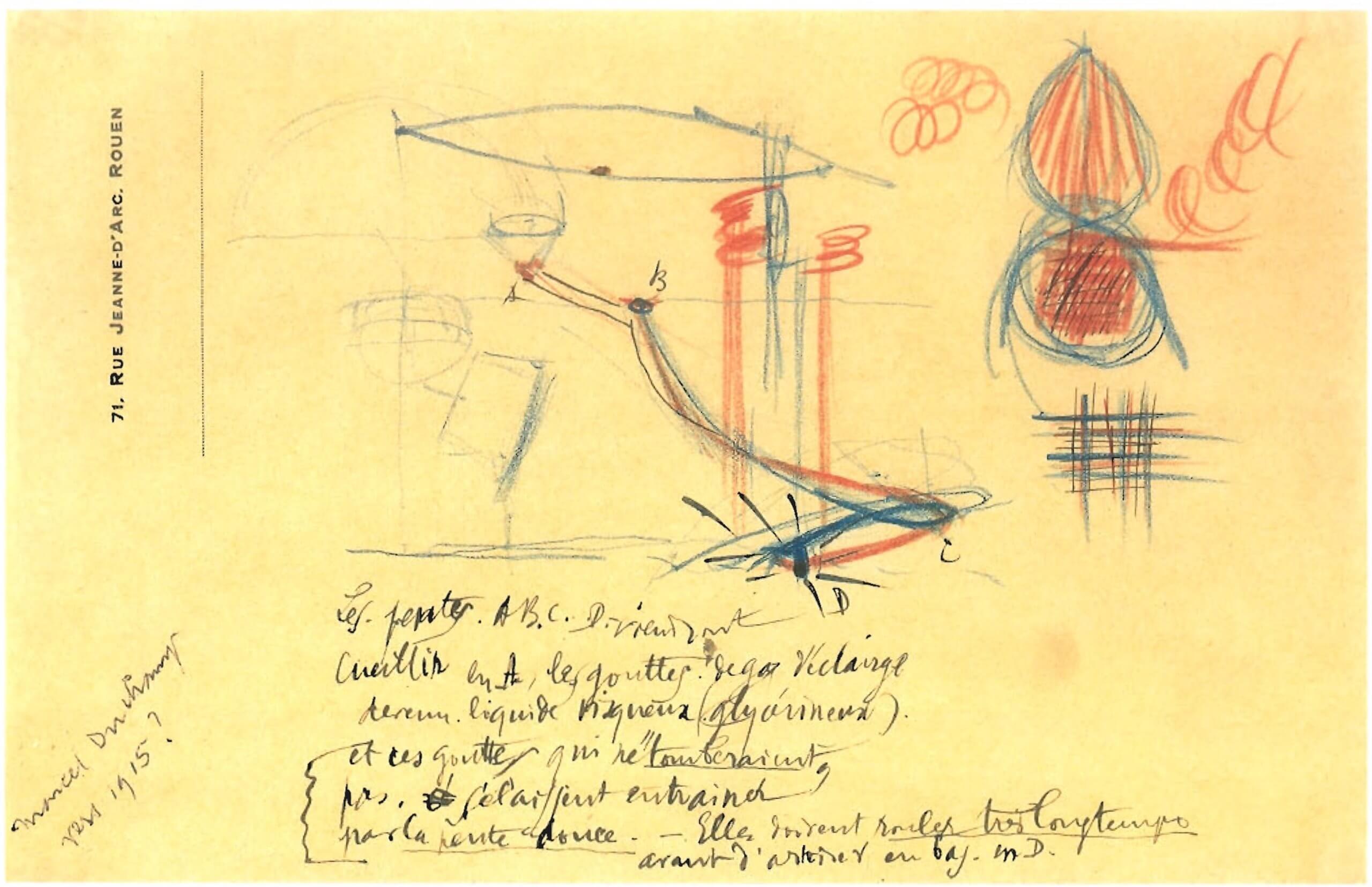

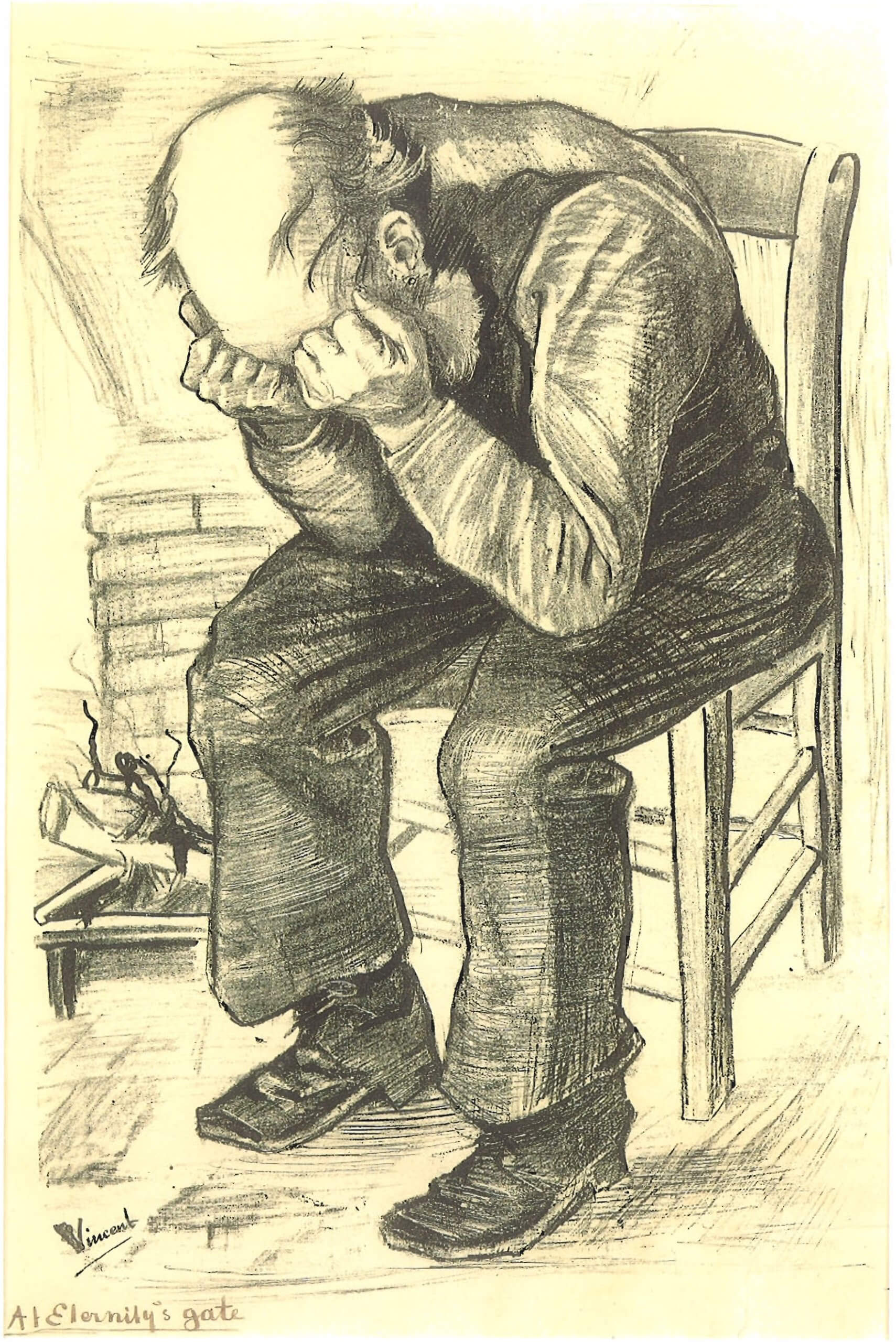

The collection she amassed included work by: Picasso, Dali, Pollock, Rothko, Matisse, Toulouse-Lautrec, Man Ray, Van Gogh, Francis Bacon, Lichtenstein, Braque, Kandinsky, Giacometti and Andy Warhol. And that’s just the tip of the paintbrush.

The exhibition was opened in celebration of the Empress’ birthday and attended by the likes of Andy Warhol and Nelson Rockefeller and was a great, but brief success.

Tragically, in 1979, the Islamic Revolution, led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini brought an abrupt end to the progress being made by the Shah and Shahbanou, who were forced into exile and Political Islam was born.

How something could halt so quickly and dramatically Stein elucidates with a quote by Colin Smith of Britain’s Observer newspaper, “Much of the religious protest movement seems to be aimed against the growing secularism of a society where, because oil had made possible what [the Shah’s] father had only dreamed of doing, changes that took centuries in Europe [had] been telescoped into a couple of decades.”

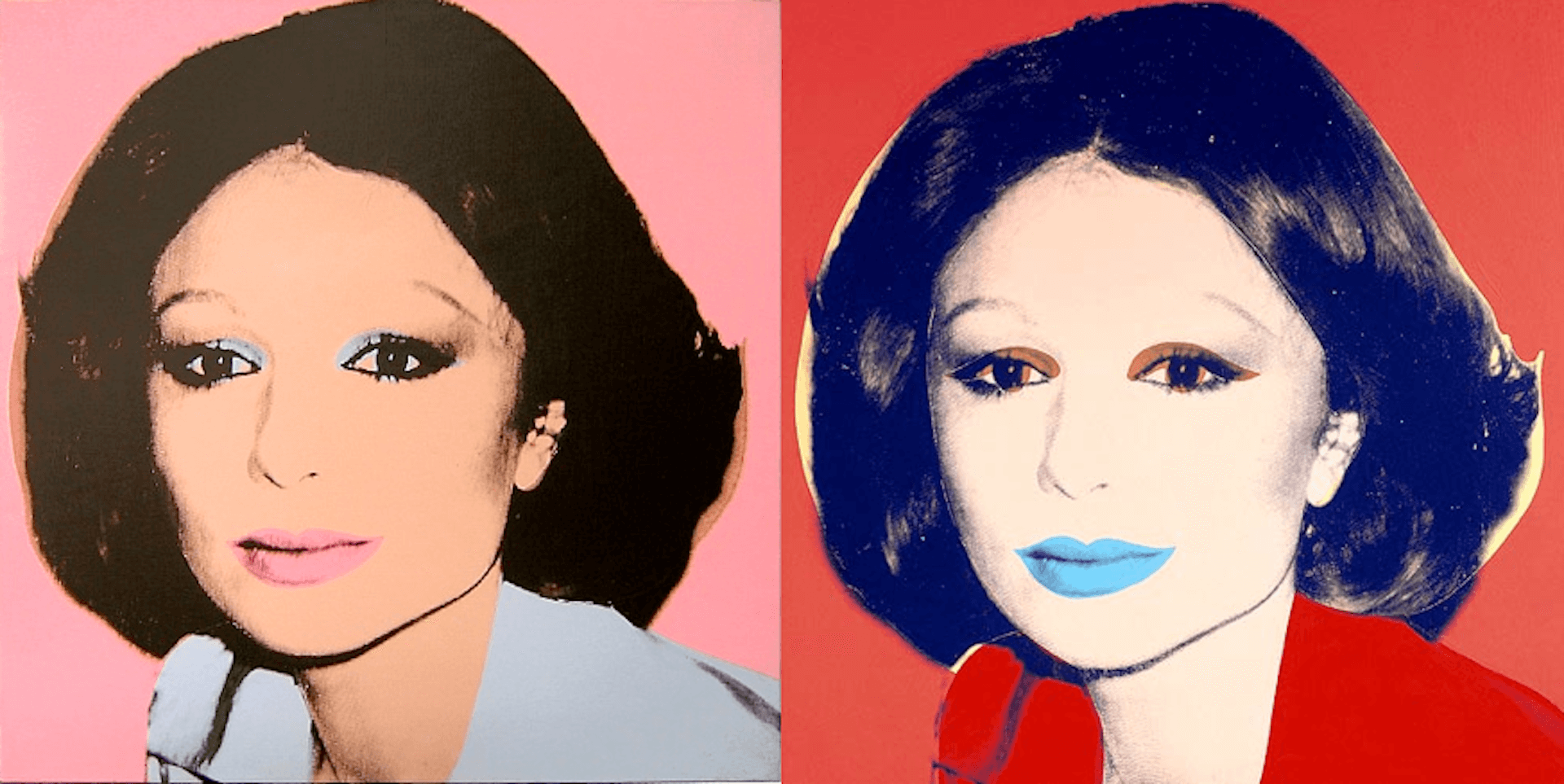

Now all of those masterworks lie in the subterranean depths of the Tehran Museum of Modern Art. Only three works were destroyed, one of them being a pop a silkscreen by Warhol depicting the Empress. The painting was a radical pop art vision of Pahlavi, a beautiful, graceful woman, often referred to as the Jackie O of the Middle East, now visually catapulted into modernity with Warhol’s depiction, which was slashed with a knife.

The current Iranian administration is nervous to lend any works for exhibition in other countries for fear that they will not be returned. Deals have been set up and fallen through at the last minute, but on a positive note, “unquestionably the most prized work to enter the Iranian National Collection,” Jackson Pollock’s “Mural on Indian Red Ground,”(1950), was displayed in Japan in 2012, at an exhibition celebrating the artist’s 100th birthday—but only on the condition that it be insured for $250 million by Christie’s.

When amNewYork Metro asked Stein about what she knew of the art scene in Iran today she described it as lively. Museums are still open—although with the Western art sequestered—and a new generation has taken a particular interest in that medium so contested when Stein was curating in the 70s: photography.

A new generation of Iranian artists is emerging—ones that don’t remember pre-Revolutionary Iran. And if large canvases can’t or won’t be transported to international galleries around the world; in our digital age, other alternatives for dissemination are possible. In “The Indigenous Lens” Stein writes, “Present-day Iran is not isolated from the world. It has a tremendously skillful, talented and Internet-savvy population that has given visibility a whole new meaning, questioning the role and power of photography in the era of social media.”

Stein’s book is an instructive memoir of adventure, the pleasure and power of art and culture, but also of friendship and loss. It is Stein’s hope that these “young, forward-looking Iranians…will continue…to express themselves beyond any limitation or border, east or west.”

After all, the internet can’t enforce travel bans.

“The Empress and I” is now available for purchase at Barnes & Noble and other bookstores for $45