It seems unfair to simply classify Elliott Sharp as musician and a composer, which he certainly is. One must also mention that he’s a writer, artist, instrument builder, teacher and producer.

But more than that, his head is a laboratory for ideas which manifest themselves constantly in an incredible variety of projects. He’s released over 85 records which run the gamut from relatively straightforward blues to avant-garde jazz to pure noise.

Sharp’s numerous collaborative partners include Debbie Harry, Sonny Sharrock, the Kronos Quartet, Christian Marclay and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, but that’s just the short list — and it doesn’t take into account the film scores and sound installations. As noted in his bio, he has “has pioneered ways of applying fractal geometry, chaos theory, and genetic metaphors to musical composition and interaction.”

That may sound daunting to the casual listener, but Sharp doesn’t mind if you don’t understand it all.

“Listening to me is a process of psycho-acoustical chemical change,” he explains. “When you hear things you respond in ways that you are not always conscious of. I’m interested in how to invoke in the listeners what the playing does in terms of my own psychological chemistry. Playing is a transformative experience, as is listening.”

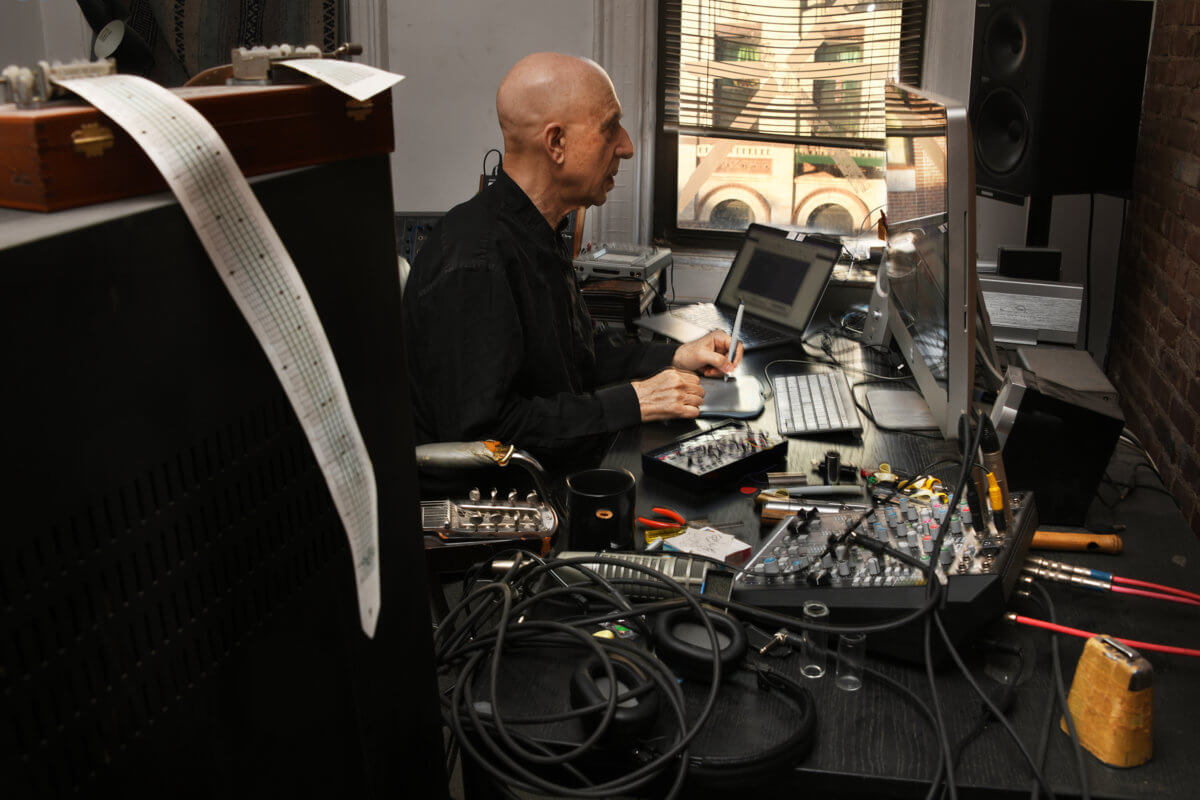

Sitting in his East Village studio where he has been ensconced for decades, Sharp recalls playing piano in a Carnegie Hall recital at age 7, moving on to classical clarinet and picking up an electric guitar as a teen in 1968.

He relates that the Ramones changed his life when he heard them in Buffalo in the late 70’s and that one of the reasons that he came to NYC in 1979 was the No New York compilation, a vinyl document of post-punk noise that Creem magazine called “ferociously avant-garde and aggressively ugly music.”

“The first person I met in New York was Dave Hofstra,” Sharp recalls. “I asked him, what do you do? He told me that he was in The Contortions (one of the bands on No New York) and I knew that I was in the right place.”

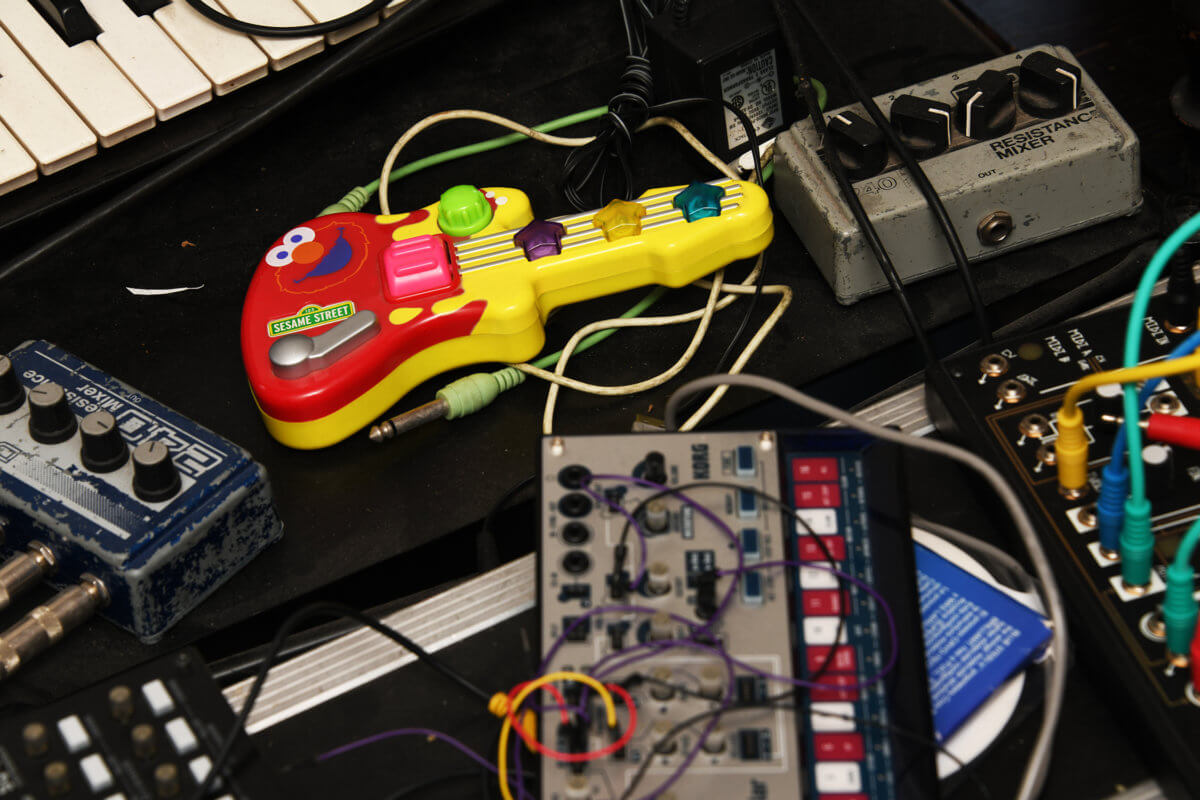

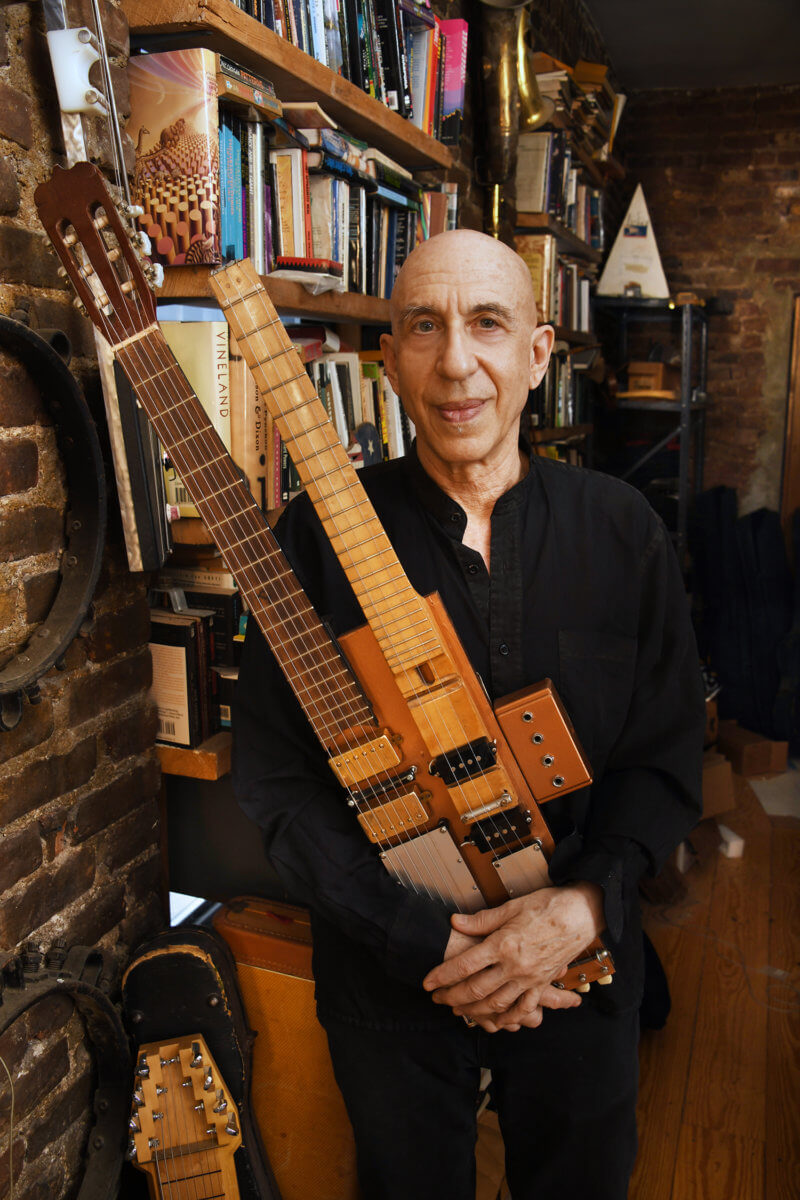

Sharp was then playing more sax than guitar and picked up gigs as a bass player, eventually learning viola and cello while experimenting with synthesizer and various electronics along the way. Not satisfied with the instruments that are readily available, Sharp creates his own “Mutantum” line of guitars and other Frankenstein creations from salvaged guitars and, well, whatever works.

“Built entirely from items in the junk box,” Sharp says, the “violameriyah” is a melding of a violin, a dulcimer and the sumsumiyah, a Bedouin instrument.

“I get some pretty amazing, non-describable sounds out of it,” he claims.

Also of note is the “Arches H-Line.”

“I built it as a tribute to the great luthier and improviser Hans Reichel who was a friend and colleague,” he says. “The name is an anagram of his name. It’s more of a sound source — it’s not tuned to anything in western intonation. It can sound like a zither or a bizarre prop on Star Trek.”

Sharp, not one to sit still, is the midst of a number of projects. In addition to releasing others’ music on his label, zOaR Records, two books will be joining his previously published memoir “IrRational Music”: “Feedback,” about consciousness and sound and “Sky Road Stories,” tales of life on tour. He’s just finished a formal composition entitled “Reseau” which includes a mix of notation and abstract, open-ended instructions for for 16 musicians.

Up next is a commission from the Multiple Joy(ce) Orchestra which will debut in Germany in October. A third album with Helene Breschand under the Chansons de Crepescule moniker is nearing completion and a new project with frequent collaborator Eric Mingus, “Fourth Blood Moon,” is also in the works. The duo will be performing at Rockwood Music Hall on October 6th.

“The pandemic worked out for me,” he admits. “I’m a fairly compulsive workaholic. I find that every idea feeds another idea. My ideas come from reading, or just walking. Often, while walking along the East River I’ve formed the seeds for a composition.”

Those compositions can be the germs of ideas for his string quartets, which he recognizes as probably his most challenging work or the more accessible Terraplane cd’s, which is a good place to start if you’re looking for some old fashioned blues played in a very modern way.

As for his approach to pretty much everything, Sharp is set on throwing away the maps and not just finding new roads, but making his own.

“People worry too much about the notes,” he muses, wrapping up. “Notes are just a certain narrow frame of sound.”

For more of Mr. Sharp, check out the website at elliottsharp.com, Instagram @elliott_sharp, Bandcamp at zoar-records.bandcamp.com and Facebook at m.facebook.com/pg/JalopyGuitars.