In the whimsical and often bewildering world of art, few stories are as delightfully convoluted as that of Sunday B. Morning. This enigmatic entity stands as a curious testament to the blurred lines between authenticity and reproduction, celebrity and anonymity, legality and loophole. Imagine, if you will, a company that thrives on replicating the work of the 20th century’s most famous replicator, Andy Warhol. Intrigued? Let’s unravel this artistic conundrum.

Warhol’s Legacy: Icons of a Pop Art Maestro

Before we dive into the Sunday B. Morning saga, a quick refresher on the man behind the mania: Andy Warhol. He began his career as a commercial illustrator, a background that heavily influenced his fascination with mass production and popular culture. Warhol’s iconic works, like the “Marilyn,” “Flowers,” and “Campbell’s Soup Cans” series, are more than just vibrant prints; they are cultural artifacts that encapsulate the essence of the 1960s.

Warhol’s “Marilyn” and “Flowers” prints, measuring 36” x 36”, are hand-pulled screenprints on heavy paper, bleeding to the edge with no borders. These prints, limited to editions of 250, are cherished relics of the Pop Art movement, with even the most blemished copies fetching exorbitant prices. As for the “Campbell’s Soup Cans,” they symbolize Warhol’s love for repetition and his daily lunch choice for 20 years – tomato soup. Ah, the beauty of simplicity!

The Birth of Sunday B. Morning

Enter Sunday B. Morning, shrouded in mystery with a name that might derive from “Sunday Belgian Morning”—or perhaps not. What is clear is that in 1970, Warhol teamed up with two anonymous Belgian friends to create a second series of prints. This collaboration aimed to further Warhol’s exploration of mass production, with the artist even providing the negatives and color codes for new editions of his famous works.

These prints were nearly identical to the original Factory Editions, complete with the cheeky “fill in your own signature” stamp—a nod to the interchangeable value of names in the age of mass production. Warhol, ever the trickster, was essentially mocking the notion that the Factory Editions were inherently superior to these new prints.

The Split and the Aftermath

However, like many artistic collaborations, this one soured. Warhol had a change of heart, possibly fearing the impact on the market for his original prints. But by then, the Belgians had all they needed to continue production. Despite Warhol’s attempts to halt the project, the prints rolled out, and he famously began signing them with, “This is not by me. Andy Warhol,” turning them into highly coveted pieces of irony.

The Legacy Continues

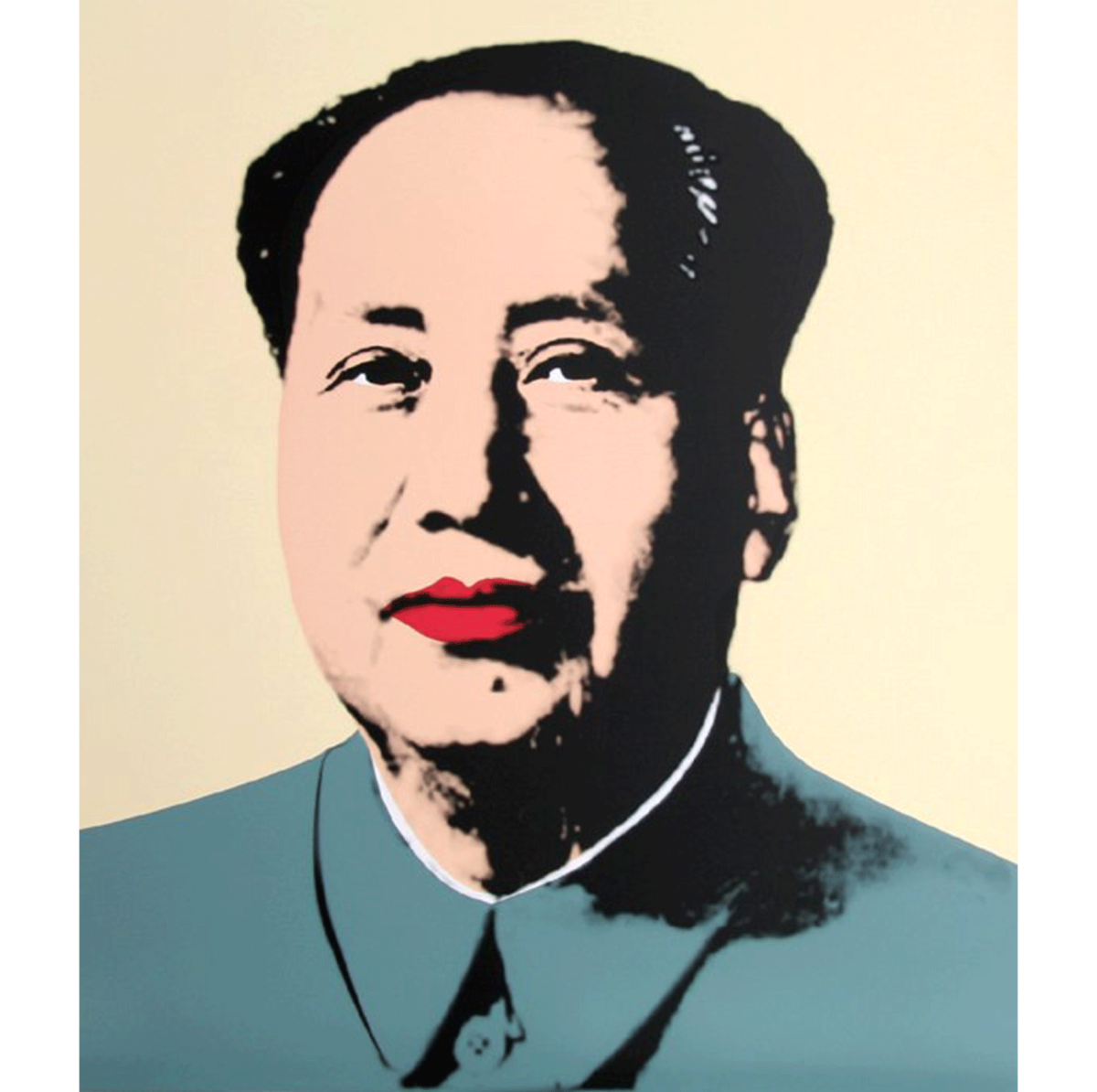

Today, Sunday B. Morning prints, with their distinctive blue ink stamp on the verso, continue to grace the art world. They now include not just the original “Marilyn,” “Flowers,” and “Campbell’s Soup Cans,” but also the “Mao” and “Dollar” series. The prints are still produced in the same Belgian print shop, using the exact processes and negatives Warhol provided decades ago.

Despite the myriad attempts by other publishers to recreate Warhol’s works, none match the integrity of a Sunday B. Morning print. The reason? Only Sunday B. Morning possesses the original photo negatives handed over by Warhol himself, a fact that gives their reproductions a unique legitimacy—even if it’s wrapped in a delightful enigma.

Sunday B. Morning stands as a playful, rebellious chapter in the story of Andy Warhol’s enduring legacy. It embodies the artist’s fascination with mass production and his penchant for irony. So, the next time you come across a Sunday B. Morning print, remember: it’s not just a replication—it’s a Warholian wink from beyond the canvas.

Currently available with DTR Modern Gallery, visit dtrmodern.com for further information or visit Soho 458 West Broadway.

Read More: https://www.amny.com/new-york/manhattan/the-villager/