This is the fifth and final installment in amNewYork Metro’s five-part series examining the proliferation of grocery delivery services across the city, and how they treat their fleet of delivery workers. Click to read parts one, two, three, and four.

Last year, as the pandemic swept New York City for the first time and forced businesses to close temporarily or altogether, there was one industry that seemed to be perfectly suited to survive: food delivery.

Demand for grocery delivery through apps like Instacart soared, and Bronx-based giant Fresh Direct launched an express delivery option, where customers could choose from a limited number of products available in just a few hours.

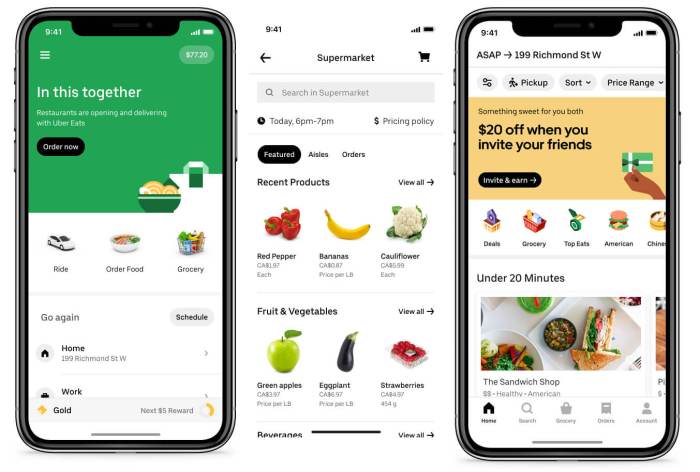

New Yorkers were also ordering more meals through apps like Uber Eats and DoorDash to get meals from restaurants, which were largely pick-up and delivery only.

New quick-commerce grocery delivery apps are at the nexus of those two markets. Companies like JOKR, Gorillas, and Fridge No More have expanded rapidly in the last year as they filled the demand for groceries delivered within fifteen minutes of placing the order via app, with low or nonexistent delivery fees and no order minimums.

At the center of all of those businesses, over the user experience of placing an order on an app or the variety of items available, are the delivery workers. Couriers zipping by on electric bicycles with an insulated bag strapped to their back have become ubiquitous in the city in the last decade, and now passers-by might be seeing a host of new uniforms and branded e-bikes as quick-commerce apps continue their steady march forward.

Employees, not contractors

Those uniforms and e-bikes mark a stark contrast between apps like JOKR and Gorillas and UberEats. The majority of delivery workers who deliver for UberEats and DoorDash are contracted or “gig” workers — essentially freelancers. They pick up work when it’s available, but aren’t employed by the company formally — there’s no guarantee of hours, wages, tips, no time off or benefits.

At most of the new grocery delivery apps, couriers are full or part-time employees, with set schedules and, in some cases, benefits.

“Unlike many delivery and on-demand service companies, all our workers are full-time and part-time W2 workers who are provided minimum wage on an hourly basis,” a Gorillas spokesperson said. “On top of that, they receive 100% of their digital tips at the end of each month, and customers are made aware of this at every transaction. In addition to compensation, they’re entitled to workplace benefits, paid breaks in compliance with local regulations, and the opportunity to return to the warehouse to refresh after each delivery.”

Gorillas riders are also provided with a company e-bike and gear including helmets, riding gloves, and a vest, according to their website.

Couriers for JOKR are also employees with benefits, co-founder Tyler Trerotola told Brooklyn Paper, and the company has made an effort to be “employee first.”

“We’ve made a conscious decision that we want these employees to have benefits, we want them to feel part of the company,” he said. “The nature of this business is very much a consumer-focused business, it’s very much about experience. Having happy employees — and employing them is furthering that customer experience. And then also, obviously, be better for that employee.”

Dangers on the job

Demand for fair working conditions and more protections under the law exploded last year, driven mostly by Los Deliveristas Unidos, a collective of mostly-immigrant delivery workers who banded together as they worked long, difficult hours through the pandemic without the protection or hazard pay offered to so many essential workers.

Even outside of working long hours in the cold, without the guarantee of an hourly minimum wage or tips, the job is dangerous. Many workers are hit and injured by cars while riding through the streets, and their electric bicycles — which can cost up to $2,000 – are often the target of violent thefts. Last month, 51-year-old Sala Uddin Bablu, who was working for Grubhub, was murdered while sitting in a lower Manhattan park during a shift.

Manny Ramirez, a delivery worker and organizer with LDU, helped his fellow workers fix their brake pads and make other repairs on their bicycles at a vigil and bike tune-up on Tuesday. He was assaulted twice this year, he said, once violently.

He immediately called LDU’s policy director Hildalyn Colón Hernández and the police, he said, who came immediately to take a report. In the past – before the Deliveristas had gained so much attention — it was hard to be taken seriously.

“Calling 911 for any emergency, they never came,” he said. “If they did come, they refused to write a report.”

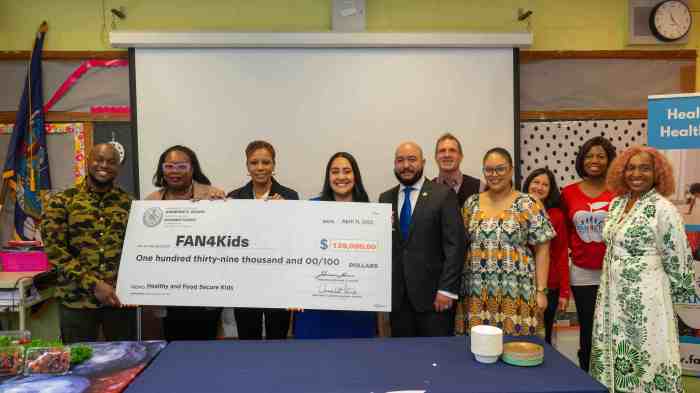

Protections for workers

The biggest accomplishment, though, has been the passage of a package of bills promising more protections in the city council, including requiring companies to provide their delivery workers with the insulated bags they need for delivery, mandating that restaurants allow gig workers to use their restrooms, allowing delivery workers to set limits for how far they are willing to go to make a delivery, and providing a clear breakdown to customers of how their tips were being distributed.

“There’s gonna be improved enforcement next year, but it helps, it helps,” Ramirez said, of the bills. “Baby steps, little by little.”

From their inception, some of the apps have abided by the rules set by the council bills, providing gear, paying at least minimum wage to their employees, and, in some cases, providing a breakdown of tip distribution on the apps. Given the small delivery radius of each dark store, riders have shorter routes back and forth.

Josh, an organizer and delivery worker with LDU who asked not to use his last name, said he has met some people who work with quick-commerce apps. Many of the struggles are the same, he said, but “it’s a different job.”

“They get their own bikes, they get a more stable wage than we do,” he said. “The Gorillas bike is supplied by the company, a lot less likely to get stolen because they are tracked.”

But just being an employee, rather than a contractor, doesn’t guarantee better treatment, Colón said.

“I think that is a false promise,” she said. “You’re part-time, or you’re earning minimum wage. But the work that they do, they should be earning even more. Just the idea that they are employees doesn’t mean that they don’t deal with issues of disqualifications, non-transparency, tips that get stolen.”

When delivery is slow or items are damaged, it’s the delivery worker who takes the brunt of the customer’s unhappiness, she said, not the company.

Gorillas workers in Berlin, where the company was founded, were fired last month after taking part in wildcat strikes calling for better treatment, saying workers are often underpaid and are not provided with appropriate weather gear. German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung reported that many Gorillas workers work on contracts, not as employees, and that many are injured on the job while carrying heavy deliveries up apartment staircases.

The Gorillas Workers Collective have posted photos of broken bicycles and screenshots they say show long hours worked and more than 50 miles covered by bike in a single day.

It’s unclear whether the council bills apply to the new grocery delivery apps, since they are not third party and are by and large working with employees rather than contractors.

“I think they don’t qualify on those grounds, on not being a third-party service,” a Council staffer said. “I think the language in the bills is individually portioned food. If you’re not delivering for something more like a restaurant or a deli, even, then those services may not be covered even if they were a third party.”

Having the laws on the books may influence companies to adopt the policies even if they don’t apply, the staffer said.

“They may be worried the public will see those things as best practices they ought to be following, they may also be concerned that legislation may come down the pipe if we start having problems with them, stuff like that.”

Ultimately, Colón said, “there’s no minimum” for how delivery workers should be treated, regardless of the company they deliver for and the status of their employment. The conversation, she said, has only just started.

“It cannot be a race to the bottom,” Colón said. “It has to be a race to the top. It’s about the people. All of the technologies you will see doesn’t matter if you just click a button. There’s human beings doing this, it doesn’t just happen.”