In 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire made history as the deadliest industrial disaster in the city’s history, killing 146 workers and setting safety standards still followed by the Big Apple. One hundred and twelve years later, the Triangle Fire Coalition on Oct. 11 unveiled the long-awaited permanent memorial at the site of one of New York City’s most calamitous blazes.

The memorial, over ten years in the making, is installed on the facade of the Brown Building at the corner of Greene Street and Washington Place in Greenwich Village. The Brown Building housed the factory, where on March 24, 1911, a cigarette tossed carelessly into a fabric scrap bin sealed the horrific fate of the sweatshop’s workers — most of them young immigrant women.

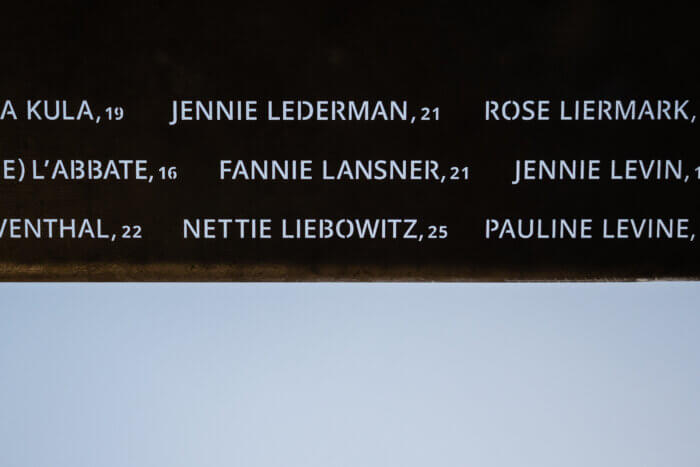

Designed by Uri Wegman and Richard Joon Yoo, the memorial is a textured, stainless steel “ribbon” hung 12 feet above the sidewalk, on the building’s southern and eastern facades. The names and ages of the 146 victims are cut into the ribbon and mirrored in a dark reflective panel as if written in the sky. Testimonies of survivors and eyewitnesses are etched as a single line of text along the lower edge of the reflective panel.

The fire’s victims did not stand a chance to escape the fast-moving inferno, as a door to one of the building’s staircases was padlocked — and the other was already engulfed in flames. Water buckets, commonly used for extinguishing fires in factories, were empty, and the fire department couldn’t extinguish the blaze because their ladders only reached the sixth floor.

The tragedy catalyzed America’s labor movement, leading to stronger workplace safety regulations, fairer wages, and the implementation of the Bureau of Fire Prevention. Elected officials and union representatives said Wednesday that the memorial served as a reminder for future generations and highlighted the importance of unions.

FDNY Executive Chief Inspector Ronald Kanterman shared that all new FDNY firefighters and inspectors are taught about the conditions at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, and the fire’s tragic outcome.

“Triangle is used as the fire prevention standard not only in New York City but across the nation,” Kanterman said. “We consistently drive the triangle story home with our inspectional staff in order to ensure that they never question what our mission is and why we do the work we do.”

Lynn Fox, president of Workers United, pointed out that while the tragedy forced the changes in labor and fire safety laws protecting workers, unscrupulous employers are eroding those protections.

“Child labor, especially among migrant children, is on the rise,” Fox said. “When you look in the faces of those children, many working in dangerous jobs, it’s like looking back in time into the faces of the workers who worked in this very building. It’s just so unconscionable, and that’s why the memorial is so needed and so timely.”

When it came to properly paying tribute to the fire’s many victims, Mary Anne Trasciatti, president of the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition, said she waited a long time to say, “We did it.”

“By honoring the Triangle workers with this memorial, we are making a statement about the dignity and humanity of every worker, past and present,” Trasciatti said.

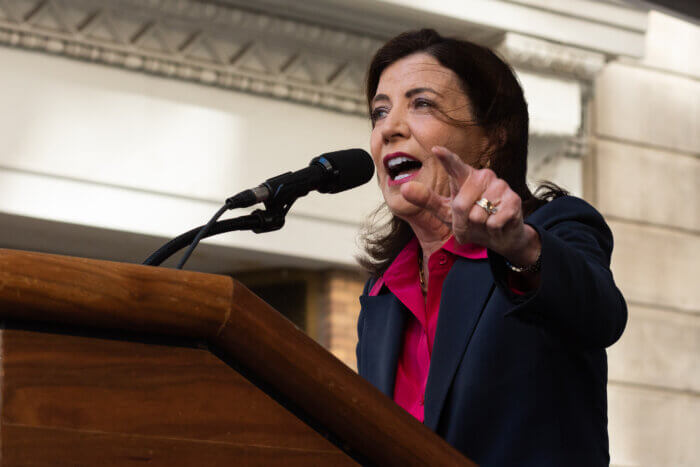

Governor Kathy Hochul also attended the memorial’s unveiling, where she told the crowd that she decided to be a champion for workers when she saw the conditions under which her family members worked in the Bethlem steel plants. Hochul said she was proud to be part of the effort to honor the names of those lost in the inferno.

“Even a 14-year-old was killed, little Rosa, who had her whole life ahead of her because she was trapped because no one would spend the money to have an escape for these people knowing that there were dangers that lurked within,” Hochul said. “We say never again. Our workers deserve to be protected, and we’ll fight to make sure they have those rights.”

The memorial means a lot to descendants like Erica Lansner, whose great-aunt Fannie Lansner perished in the fire and was hailed as a hero on the front page of the New York Evening Telegram in 1911.

The 21-year-old forewoman, who immigrated to the United States from Lithuania with her brother in 1907, saved many lives, helping some workers down the stairways while ushering others into the elevator trip after trip before the elevator eventually broke down. Surrounded by flames and with no other way out, Lansner jumped to her death from a ninth-floor window.

At Wednesday’s unveiling, Erica Lansner said it was “very moving and meaningful” to have her great-aunt’s name enshrined in history.

“I’m very proud to be a descendant of hers,” she said. “When we found out that she was hailed as a heroine and helped others to safety like that, it makes me proud to be a Lansner.”