Osceala “Ossie” Fletcher’s blood ran red like the rest of the American casualties on the beaches of Normandy nearly 80 years ago — but the color of his skin led to the denial of what others who survived that hellish D-Day battle received: a Purple Heart.

The World War II hero from Crown Heights, Brooklyn, at age 99, finally received his Purple Heart at a special ceremony at Fort Hamilton Army Base in Brooklyn on June 18 — a day before the first federally-recognized “Juneteenth” national holiday that ended slavery of African Americans after the Civil War.

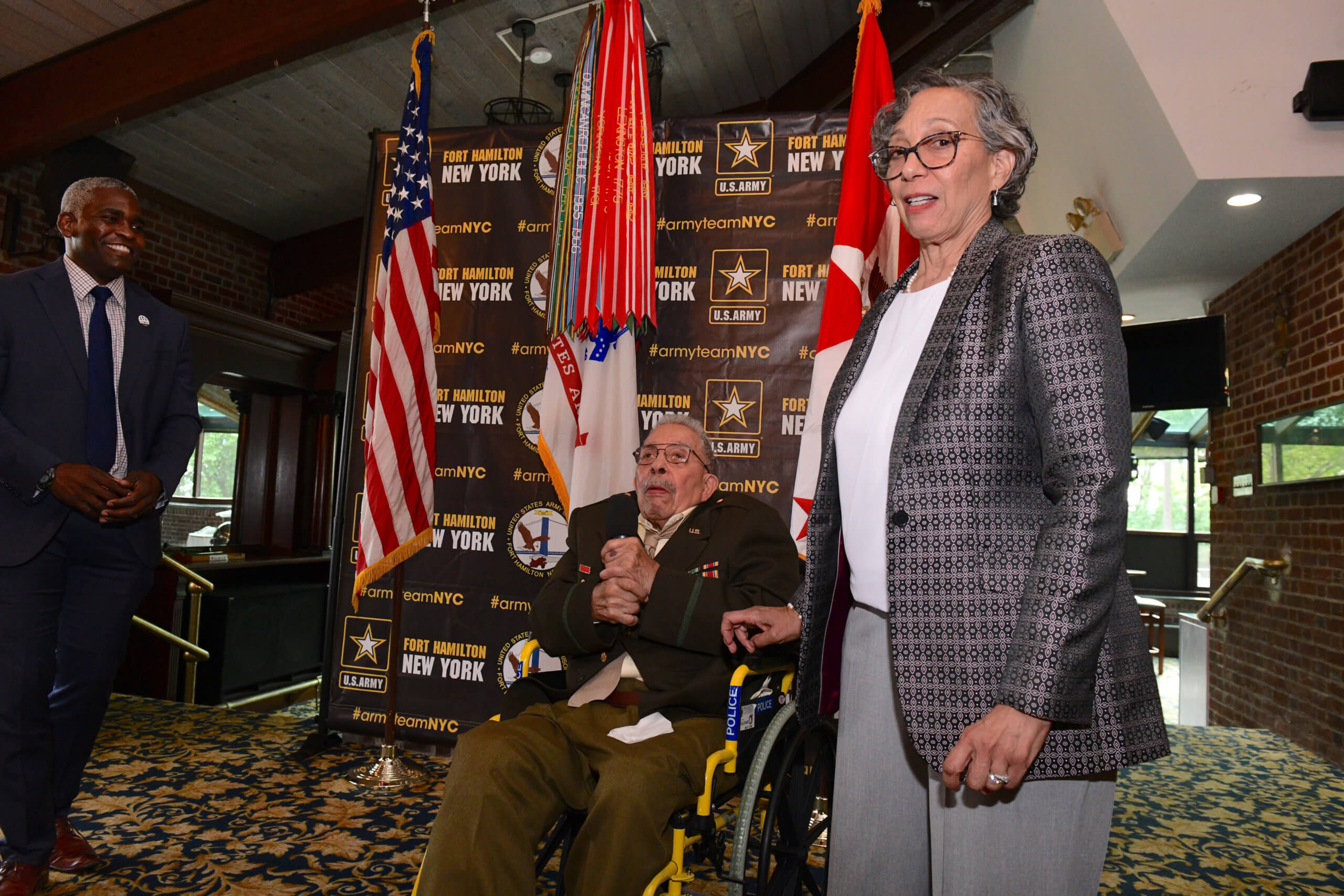

Fletcher attended the ceremony with his wife Pauline, his daughter Jacqueline Streets, a dozen family members and one great grandson. The wheelchair-bound Army veteran, a crane operator in the 254th Port Battalion, was wounded three times, most notably during a German rocket attack that left a scar on his head and a gash in his leg.

Despite his inability to walk on his own, the nearly 100-year-old veteran insisted on standing during the National Anthem, assisted by Police Officer Ming Yu, a Marine veteran and current member of the NYPD Harbor Unit.

Fletcher had also served a sergeant in the NYPD in his post-war years before retiring and then becoming a social studies teacher in New York City public schools. He also served as a community relations officer in the Brooklyn District Attorney’s office.

The former private first class collected his medal from U.S. Army Chief of Staff General James McConville during the emotional ceremony at the historic Fort Hamilton Community Club in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. He was joined by Secretary of the Army Steve Castleton, Brigadier General Thomas Tichner, and NYPD Commissioner Dermot Shea.

“Ossie has spent his entire life giving to those around him, and well, today is Ossie’s turn to receive and today we are giving him,” McConville said during the tearful ceremony. “Now, we are delivering something that he’s been entitled to for over 77 years … Today, we pay long overdue tribute for the sacrifices he made to our nation and for free people everywhere. Now let’s get you the Purple Heart you are due.”

The general then knelt down next to Fletcher and pinned the Purple Heart on him next to three other medals he wore for his military services.

Fletcher’s daughter, Jacqueline Streets, said she and her family sought the records of his injuries for years, finding out at one point, that those records had been destroyed in a fire in 1973.

“We’re finally looking at all of our soldiers in the same way, America is trying to shift its thinking about culture and about race and I appreciate that,” Streets said.

“It’s about time,” said Fletcher after recalling his daughter learning ballet, going off script in a light moment. “You will remember the Fletcher name now.”

In addition to praising his fellow veterans, many of whom have passed away over the years, he also extolled the French people who he said “fought bravely against the Germans and were always there to help us during the war.” He spoke in French for the benefit of Jeremie Robert, consult general for the French embassy.

His daughter had to interrupt the talkative Fletcher in French. “I think its time to wrap it up,” she quipped. “He’d go on and on if I didn’t stop him.”

Fletcher sailed to Europe from Portsmouth, Va., aboard a segregated ship where Blacks were forced to stay below deck as they departed for the war. However, bullets made no racial distinction as 425,000 American soldiers were killed or wounded in 12 weeks of fighting the Nazi war machine.

Among those also in attendance was Helen Patton, granddaughter of General George Patton; Henry Roosevelt, grandson of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt who also produced a film about the survivors of D-Day entitled “6th of June”, and member of the Comus Club of Brooklyn, a Black fraternal organization from Brooklyn that does charity work within their community.