By Paul Thaler

The word of my teacher’s death came through the Internet, something that Neil would have wittily complained about. It was said that Neil Postman never met a computer — or a typewriter for that matter — he ever liked. There was truth to that. His 20 books and countless articles and speeches were all written by hand, in graceful strokes, on a legal pad with a felt-tipped pen, a way of writing more appropriate for another era.

In fact, Neil never fit well into the new age, caught in the present only by virtue of his birth. Many of his students, and there were thousands of us, thought he would have preferred being born in the 18th century and could envision Neil schmoozing with the Founding Fathers about freedom and democracy, and where to find the best tuna fish sandwich in New York City. Intellectual, humanist and kibitzer, I have no doubt that Neil would have charmed James Madison.

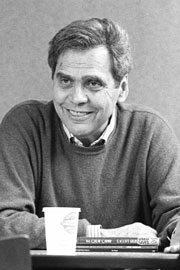

Neil was in certain respects a living contradiction. A leading academic at New York University for 44 years, and the most prolific media critic in the country over the last half century, he took pride in having never written a single academic journal article in his long career. His ideas were meant to be read by people, all people, and not a narrow niche of Ph.D.s. Similarly, in a new media age, Neil was defiantly old media, firmly convinced that books — and their Great Conversation from Plato to Marshall McLuhan (his own mentor) — were civilizing agents that made us smarter and, more importantly, made us more human.

He was fearful that we were losing our grip on books, that television was taking over cultural discourse, turning everything from our national politics to our criminal trials into the stuff of entertainment. We don’t have to look further than Arnold and Kobe to understand the clarity of his ideas.

Most of all, he kept his critical eye on children and their education. “Children are the living messages we send to a time we will never see,” he wrote, pondering the world they would arrive at in such books as “The End of Education” and “The Disappearance of Childhood.” Neil himself carried a childlike wonder into his classroom. I would often observe him in class, his eyes glued to a speaker, his mouth slightly ajar as if he was about to ask a question. He invariably would, and pity the poor academic who had turned the English language into nonsensical jargon — the worst faux pas of all. Neil’s gentle ax of a question might be paraphrased as such: “Now what the hell do you mean?”

I first got to know Neil in the mid-1980s as a student in his doctoral program at N.Y.U. He had founded and named the program in the early 1970s, something he called media ecology, with its orchestra of eclectic thinkers like McLuhan, Jacques Ellul, Walter Ong and many others, that challenged the current intellectual tides of media studies. I wasn’t sure what to expect when I arrived. But the medium of Neil’s classroom was the message. Wafts of cigarette smoke coming from teacher and students alike coated our lungs and clothing, the ramshackle classroom, a place Jack Kerouac would have felt right at home at. The class conversation — always an energizing flight of ideas — would inevitably carry over the following day into the nearby Violet café off Washington Sq. or at Neil’s desk where he would hold court with anyone who came by. And we came by all the time to sit and schmooze.

For Neil, as I would discover, any place was his classroom, and anyone he encountered was a potential student. I recall a number of years ago touring Jerusalem’s Old City with him as part of a conference trip. Outside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre sat a serious looking 15-year-old Palestinian, a person ignored by all passersby. But not Neil. The old Jewish kid from Brooklyn sidled up to this Arab boy on a stone ledge, easing him out of his shell to talk, however haltingly in broken English, about his life. For Neil, it was another moment for making a human connection.

The basketball court was probably where I got to know my teacher best. It was hard to imagine that this 60ish professor with the old-fashioned two-hand set shot was once among the leading scorers in the nation in the 1950s while playing for Fredonia University in Upstate New York. At a media ecology conference Neil ran each year at a rundown lodge in the old Catskills, we had our annual pickup game. The lodge was short on hot water and sported a broken-down basketball rim. There we would take on all comers — and I always made sure I was on Neil’s team. What Neil now lacked in athletic skills, he made up by psyching out younger, stronger men, then using his guile to run the pick and roll. In all the years we played, we never lost a game. Never.

I always felt I had a special bond with Neil, but I have learned over the years that most of his students felt the same way. This was Neil’s gift as a teacher. All his students felt cared for and all thought themselves special in his eyes. And, in fact, they were. A number of us went from student to teacher in Neil’s program before taking up professional residence in many of the area colleges and universities. When I recently arrived at Adelphi University, I discovered that every one of my colleagues had at some point in their education studied with Neil.

Former students went on to honor Neil in other ways. The Media Ecology Association was born, and just two weeks before his death the academic group honored Neil at their fifth anniversary ceremony at Fordham University. Most in attendance hadn’t seen Neil in months. Now tied to an oxygen tank, looking frailer, our teacher was still in typical form that night, holding court, again our wise mentor, and cracking wise. It was the last time any of us would see him again. Looking back on that night, though, we felt blessed to have had a final chance to say goodbye.

On a bright fall October morning, hundreds of us came to pay our last respects and shed tears for the great man, crammed into the funeral house on Queens Boulevard. Midway though the rabbi’s eulogy, a cell phone went off, loudly, stunning those of us in the chapel. Then some nodded their heads knowingly. Neil would have had a good laugh — you see, he would say in that slow gravelly voice of his, just another example of technology getting in the way of our human connections. I suppose the saving grace was that the errant cell phone had struck up a mechanical rendition of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” before finally stopping. This our teacher surely wouldn’t have minded. “Now that’s a song worth listening to,” he would have said with his ubiquitous, knowing smile.