By Rachel Holliday Smith, THE CITY

This article was originally published on by THE CITY

The first time Shams DaBaron realized not everyone on the Upper West Side wanted the homeless shelter where he was staying gone, it was in a message written in chalk under his feet.

DaBaron, a writer and advocate who goes by the name Da Homeless Hero, walked out of the Lucerne Hotel on West 79th Street, where he and more than 200 homeless men have been living during the COVID-19 crisis.

On the sidewalk outside, locals had scrawled messages. At first, DaBaron assumed it was the usual “derogatory stuff,” he told THE CITY, like comments he’d seen in some media coverage, on social media and in the backlash to the men living there.

But then a security guard told him to take a closer look.

“I’m seeing, ‘We love you.’ ‘Welcome to the neighborhood.’ ‘Everyone deserves a home,’” DaBaron said. “And I’m like, ‘What happened? What did I miss?’”

The messages had been written on Aug. 9 by neighbors who were just starting to organize as the UWS Open Hearts Initiative.

The group formed in opposition to the barrage of negative attention the Lucerne got from less welcoming Upper West Siders, who eventually threatened a lawsuit against the city. Shortly afterward, Mayor Bill de Blasio ordered the Lucerne residents to be moved.

Next Stop: Lower Manhattan

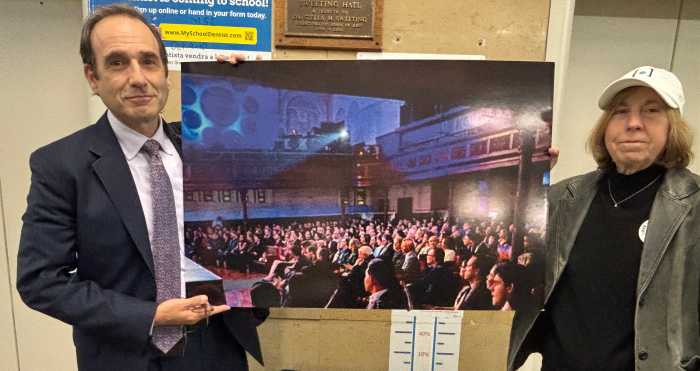

Since the summer, Open Hearts — led primarily by West Side moms who volunteer on top of full-time jobs — has organized events and political actions on behalf of the men, from charity drives to a march to Gracie Mansion. The group has a volunteer list of roughly 100 people, of which a half-dozen members do the core organizing, according to co-founder Corinne Low.

Now, because of the mayor’s order, they’re taking their expertise on the road to help others in the fight to be neighborly to shelters.

The next stop is in Lower Manhattan, where shelter provider Project Renewal and the city Department of Homeless Services are readying the Radisson Hotel on William Street to host men from the Lucerne.

They are slated to move there by the week of Oct. 19, according to a DHS official who spoke to Manhattan’s Community Board 1 about the plans last week.

The Radisson is one of three commercial hotels in Manhattan’s Community District 1 being used as temporary housing during the COVID-19 crisis, DHS said. In the long term, the agency has said it plans to convert the Radisson to a permanent shelter for adult families — meaning couples or a parent with an adult child.

As those plans move forward, a well-funded legal battle is brewing, mirroring the West Side fight.

The newly formed group Downtown New Yorkers for Safe Streets is looking to raise $1 million to fund a lawsuit and has hired veteran attorney Kenneth Fisher, a former City Council member known as “the fixer” in contentious cases. Neither Fisher nor his client returned requests for comment.

Neighborhoods Talk

At the same time, those who want to publicly support the residents of the Lucerne are getting organized, too, informed and inspired by the Open Hearts playbook.

Calling themselves Friends of FiDi, the fledgling group had its first Zoom meeting this week, explaining their mission and hearing from DaBaron, who logged on from his room at the Lucerne.

Karin Elgai, a stylist and downtown mom, was one of about about 25 people on that call. She had contacted the Friends group soon after hearing about the shelter’s move to the Radisson.

Earlier this month, she, her husband and their 1-year-old son visited the Lucerne, getting to know the residents, including DaBaron, at a “free store” item-donation event hosted by Open Hearts.

“It’s important to understand that we’re way closer to this situation than we think,” Elgai told THE CITY, referring to homelessness.

She knows something of what the men are going through, having struggled with addiction and now nearly seven years of recovery, she said. For a time, Elgai lived in a storage unit in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, and showered at a gym.

The experience — which she stressed was not comparable to the challenges faced by the men at the Lucerne — taught her that anyone is “one day away from having our life completely change,” no matter how much privilege they start with.

Ideally, she would prefer the men stay where they are to avoid “the entire trauma, the hostility and negativity again.” But if they have to move, she is ready to help them however she can.

Cait Dooley, a co-founder of Friends of FiDi, echoed the sentiment.

“We don’t agree with the mayor’s move of the Lucerne residents,” she said. “However, if that move is taking place, we think it is incumbent upon us … to make sure that these men receive a compassionate welcome to the neighborhood.”

‘Make Your Support Known’

Though it’s not unheard of to see New Yorkers welcome a new shelter in a neighborhood, the mobilization of Open Hearts to help the men of the Lucerne represents a different level of vocal and political support for shelter residents.

It’s something that Low, a co-founder of the West Side group, hopes can be replicated in neighborhoods all over the city.

She acknowledges that “none of us were actually experts in homelessness” when Open Hearts began. But, she noted, the group has learned a lot about how to organize and hopes to create virtual toolkits for anyone eager to show up in support of homeless New Yorkers.

“When DHS wants to place a shelter, all the opponents will get on the community board meeting and yell about how they don’t want it,” Low said.

Meanwhile, the people who are “just happy for it to be there” generally don’t make their voices heard.

“They are not thinking like, ‘Oh, let me go yell at my elected officials,’ you know? They’re thinking ‘Oh, I’ll show up with cookies,’” she said. “You need to make your support known. You need to make it vocal.”

Those who get loud, however, should be ready for blowback. Low and her co-founders have been harassed online, she said, and their home addresses were posted on social media. A thick skin and an ability to not engage is key, she added.

For some men at the Lucerne, the barrage of complaints has become too much, DaBaron said. He’s spoken with a handful of residents at the hotel who are considering returning to the streets rather than deal with whatever comes in the Financial District.

“We’re used to moving around. But the thing is this: the fear that we may get even more of a negative backlash somewhere else is traumatizing,” he said.

Not Just Kind Words

The work of those who support shelters needs to go far beyond kind words — something DaBaron emphasized to Open Hearts early on.

When he first saw the chalk-written sentiments in front of the Lucerne, he looked up Open Hearts online and wrote to the group right away, with some gentle criticism.

“I was saying, look, writing chalk on the ground is good. It’s cute. I like it. And it does a little bit. But it’s not enough. We need a lot more,” he recalled.

A member of Open Hearts, Amanda F., asked to meet with him, and they sat on a bench near the Lucerne and brainstormed ways the group could help. Within 20 minutes, he said, Amanda — a local mom in recovery herself — volunteered to lead a weekly Alcoholics Anonymous meeting at the hotel.

Amanda, who shared only her last initial due to the anonymity of the group, said getting those meetings on-site at the shelter was key since DaBaron said Lucerne residents felt they couldn’t show up to local AA meetings.

“Based on what they had been reading was being said about them, or even how some they were being spoken to on the street … made them scared to go to a meeting,” she said.

The recovery meeting, held every Sunday night on the top floor of the hotel, is just one of the ways Open Hearts has pushed for services and material support for the men.

They organized a donation drive to buy the residents MetroCards, created an Amazon wishlist for items the men need, set up the “free store” stocked with donated clothing and household items, and organized “soulful walk and talks” to Riverside Park with local faith leaders, DaBaron said.

“It’s not a sermon. It’s not a church. It’s none of that,” he said. “We just have a circle and just talk.”

Downtown, Friends of FiDi is aiming to replicate some of those approaches. Elgai has volunteered to host a recovery meeting for the Radisson residents, and Amanda is working with Project Renewal to set that up.

Friends of FiDi is also looking for volunteers to create welcome kits with socks, hats, water bottles and energy bars — as well as MetroCards, handwritten notes to each resident and homemade baked goods.

Dooley said a big focus, too, will be fighting misinformation. For example, she’s seen rumors that the men are sex offenders posted on Facebook and elsewhere. Through Project Renewal, Dooley confirmed that claim is untrue.

“We are really working at trying to inform people and quell a lot of the fears,” she said.

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.