BY DUSICA SUE MALESEVIC | Like boxers lacing up their gloves before a bout, community groups are readying themselves with studies, statistics, and strategies as the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey eyes its bus terminal expansion.

It is unclear whether the Port Authority will replace or renovate its aging facility on Eighth Ave. (btw. W. 40th & 42nd Sts.). During this period of uncertainty, advocacy organizations like CHEKPEDS (Clinton Hell’s Kitchen Coalition for Pedestrian Safety) and the newly formed Hell’s Kitchen South Coalition have designated air quality a major concern for whatever plan moves forward.

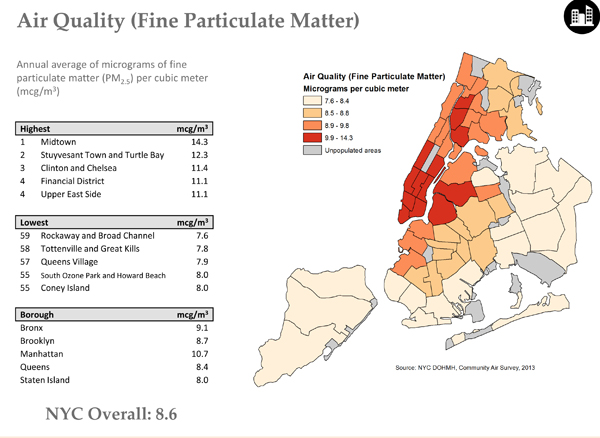

City data on air pollutants show why: Chelsea and Hell’s Kitchen have the third-highest annual average of a fine atmospheric particulate matter called PM2.5, deemed the “most harmful urban air pollutant,” according to the New York City Community Health Profiles Atlas from 2015, the latest year available, and the city’s air survey. Midtown is first citywide for the particulate, followed by Stuyvesant Town and Turtle Bay.

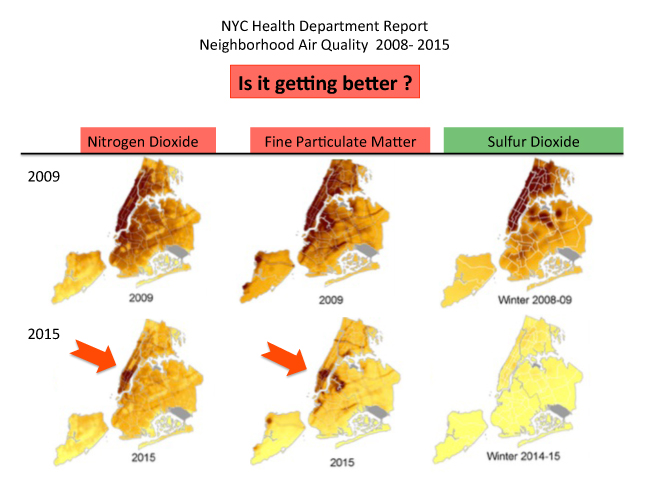

The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) established the New York City Community Air Survey in 2007, and the most recently released report in April focused on air quality in neighborhoods from 2008 to 2015. The survey measures a myriad of air pollutants that includes PM2.5, nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide, according to the report.

Christine Berthet, a member of CHEKPEDS, used city data to discuss air quality in a presentation to a Community Board 4 (CB4) committee last week.

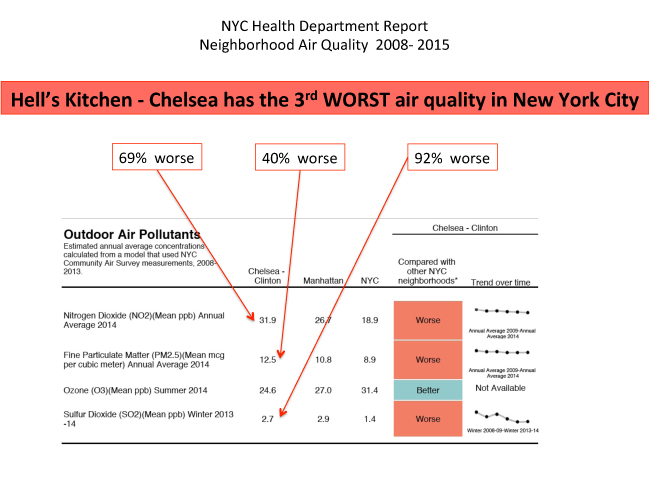

“Our whole city is already in the bad shape,” Berthet, who is also a CB4 member, told the Waterfront, Parks & Environment Committee at their Thurs., Sept. 14 meeting. But the air quality in Chelsea and Hell’s Kitchen “not only is it worse, it is way worse,” she noted.

Compared with other city neighborhood annual concentration averages, the area is 69 percent worse when it comes nitrogen dioxide, 40 percent for fine particulate matter, and 92 percent worse for sulfur dioxide, Berthet said.

“We are not making progress here,” she said. “We are not on the right track and that’s very concerning.”

The area had a higher traffic density than both Manhattan and the city as whole in 2005, according to the survey. “The New York City clean air survey data has shown the connection between the bad air quality and the traffic,” Berthet said. “There is no real question that what’s coming out of the Port Authority and the Lincoln Tunnel have a major impact… on our environment and the air quality.”

Berthet pointed out that while the existing population was 103,245 seven years ago, there were 226,000 daily bus commuters and 142,484 daily car commuters passing through the area, according to 2015 figures. An influx of new workers once Hudson Yards is up and running could add another 125,000 by 2025.

“That’s not a small population,” she said. “People think about we are in the no-man’s land here but there are 47 schools and pre-Ks within half a mile of the Port Authority.”

She added, “This is a major, major crisis for our neighborhood.”

Air quality also seems to disproportionately affect low-income residents — they are about nine times more affected by low air quality, she said.

CHEKPEDS was founded around 10 years ago, and the pedestrian safety group has always kept air quality in its sights. “As part of this work, we’ve been very, very active on the air quality. Because, indeed, when you are walking, you cannot walk safely without being able to breathe,” Berthet said.

The group tackled bus idling as well as finding more parking spots for buses, she said. Berthet said one of the main reasons a driver leaves the engine running is because there is nowhere to park, and they are looking to avoid getting a ticket. In New York City, a vehicle can idle for three minutes but only one minute in a school zone with fines ranging from $115 to $2,000, according to a flyer Berthet handed out at the meeting.

“One of the major problems we have with the Port Authority bus terminal is the amount of idling that not only the buses but also the cars backed up from the Lincoln Tunnel spew in our neighborhood,” she said.

Earlier this year, the Port Authority announced it would conduct a study on renovating its current location, known as the “build-in-place” option. The authority’s board is tentatively scheduled to get a presentation on that option at its Sept. 28 meeting, Steve Coleman, spokesperson for the Port Authority, said in an email. Coleman said the specific agenda for the meeting would be issued on Sept. 22.

The Port Authority issued a request for proposal (RFP) in June for the environmental work for the new terminal, Coleman said, but only one proposal was submitted though it was posted and publicized for six weeks.

“Since Port Authority practice is typically to get two or more proposals to maximize competition, the environmental RFP will be combined with one for preliminary architectural/engineering services and will be reissued in the fall,” he said.

Estimated cost of the project could hit $10 billion.

The Hell’s Kitchen South Coalition was formed around issues related to the Port Authority’s bus terminal plans, Rev. Tiffany Triplett Henkel told the committee. “In May, we had another meeting of the full coalition where we identified air quality as a major concern.”

The coalition has called upon the Port Authority “to reduce the number of buses that will travel to Midtown in the future and to start immediately to reduce the current congestion caused by idling, gridlock, and the spillover of the Port Authority bus operation in our streets,” Henkel said.

JD Noland, a committee member and Hell’s Kitchen resident, said that the Port Authority wants to build a terminal to accommodate a 40 percent increase in capacity by 2040. “It’s an enormous increase in capacity. They want to build a bigger terminal in Hell’s Kitchen,” he said.

Berthet said that the Port Authority wants a staging area for the buses. “The problem with that is that the staging area is just a massive queue, which is going to be idling for five or six hours a day for 500 buses,” she said. “If we’re going to take more buses in New York City — maybe, right, we’re still fighting that battle… We don’t want that staging. Period. That’s it.”

In addition to fighting against a staging area for buses, Berthet enumerated other “targeted strategies for various bus activities,” shown on one of the last slides of her presentation, which included advocating for an enclosed terminal and parking, and underground ramps.

She said, “We’re going to have to have a big fight on our hands and that’s where we are going to use all that information.”