By Julie Shapiro

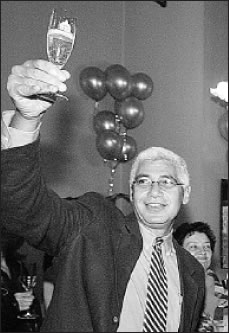

Albert Capsouto, pioneering restaurateur and advocate for small businesses, died Jan. 19 at the age of 53, just two months after he was diagnosed with a brain tumor.

Capsouto was a familiar face in Tribeca ever since he and his two brothers opened the French bistro Capsouto Frères on Washington St. in 1980, long before the neighborhood was a restaurant destination. Capsouto also served on Community Board 1 for more than 19 years, and he called the board his second family.

“He was a significant character in the story of Tribeca,” said Rocco D’Amato, owner of Bazzini grocery and nut shop.

Madelyn Wils, former chairperson of C.B. 1, said Capsouto’s death leaves “a huge hole in the fabric of this community.”

Capsouto and his brothers arrived in Tribeca when the neighborhood could still be called a frontier. They bet on the old manufacturing district’s future, building a restaurant near the Hudson River on a block that stayed quiet after dark. Soon, Capsouto Frères was a center of Tribeca’s fledgling community, one of the only placesTribeca residents could walk to to get a good meal at night.

“It was exciting,” said Carole De Saram, a longtime Tribeca resident and C.B. 1 member. “It was a place that everybody went to.”

As Tribeca began to change, and residents and small shops replaced the warehouses and wholesale stores, D’Amato urged Capsouto to join the community board to help with the transition to a mixed-use neighborhood. Capsouto agreed, and his practical, patient voice became influential on everything from liquor license applications to the1995 rezoning of Tribeca.

“At the beginning, he thought of me as a mentor,” D’Amato said. “But it wasn’t all that long before the student became the teacher.”

After 9/11, Capsouto and his brothers kept their restaurant open to serve rescue workers and to give people a place to come together. Capsouto also redoubled his advocacy for small businesses, serving as chairperson of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation’s Restaurants, Retailers and Small Business Advisory Council, and traveling to Washington, D.C., to fight for financial assistance. He helped many fellow entrepreneurs fill out forms to get aid, and in 2003 he received a Phoenix Award for Small Business Economic Injury Recovery from the U.S. Small Business Administration.

Capsouto’s friends described him as a humble yet persistent force on community issues.

“You could always rely on him for objective common sense,” said Wils, the former C.B. 1 chairperson. “He didn’t have an agenda, other than to help small businesses. … He did what he did because he loved this community, not because he was trying to make a name for himself, as so many others do.”

Wils, who now works for the city’s Economic Development Corporation, remembers the precise day she met Capsouto: It was April 30, 1981, and she was on a first date with the man she would marry two years later. Wils’s husband-to-be took her to dinner at Capsouto Frères, and Wils was impressed by the “Downtowny” vibe. Two years later, Wils held her rehearsal dinner for her wedding there.

Wils got to know Capsouto better when they served on the community board together, and she appointed him to chair the Tribeca Committee. In addition to the rezoning of Tribeca, Capsouto fought for the completion of Hudson River Park and the landmarking of swaths of Tribeca. He often arrived at meetings on his bike, which he rode all over Downtown.

Capsouto was born in Cairo, Egypt, in 1956, the youngest of three brothers. The family, Sephardic Jews, moved to Lyon, France, in 1957, fleeing the Suez War, and then continued on to New York in 1961. Capsouto attended Stuyvesant High School and graduated at the top of his class.

Capsouto’s eldest brother, Jacques, recalled that Albert had trouble filling out his application to Yale University because it only gave one page for the essay, and Capsouto had much more than that to say. Using a narrow-tipped pen, Capsouto managed to cram four lines of writing onto every line of the page.

Yale accepted him, and Capsouto earned a bachelor’s in architecture and engineering.

After completing college, Capsouto returned to New York and soon began working with his older brothers on the family’s longtime dream of opening their own restaurant. The brothers bought the high-ceilinged landmarked building at 451 Washington St., and Capsouto used the expertise from his newly acquired degrees to transform the warehouse into a restaurant.

“We did O.K.,” Jacques said of the restaurant’s first months. “We weren’t even thinking about not making it.”

Albert, who was 24 when the restaurant opened, ran the front of the house, welcoming guests and often stopping by patrons’ tables to chat.

At the 25th anniversary of Capsouto Frères in 2005, Albert said he and his brothers drew inspiration from meals shared with their mother, Eve, who died in 2003.

“It’s not just the food — it’s the meal,” Capsouto said in a 2005 interview with Downtown Express, The Villager’s sister paper. “And the meal consists of the company, the atmosphere, the service, the music. It’s a very nurturing place.”

Capsouto’s diagnosis and swift decline last fall came as a sudden blow to his brothers and the tight-knit Tribeca community. In addition to sharing a job, Jacques and Albert also shared a home in the building across from the restaurant, which the family owns.

“I lived on the fifth floor, and he lived on the fourth floor,” Jacques said this week, his voice breaking. “We had a beach house together on Fire Island. How much closer can you get?”

More than 400 people attended Capsouto’s funeral last Wed., Jan. 20, at Riverside Memorial Chapel on the Upper West Side. He is survived by brothers Jacques and Sammy Capsouto, and Sammy’s wife, Kathy, and her and Sammy’s three children.

Before he got sick, Capsouto was active at New York Downtown Hospital and was going to be named to its board. Jacques asked this week that in lieu of flowers, people send donations to the hospital in Capsouto’s memory.