From the start, amNewYork Metro has been a paper of the commuting New Yorker, particularly subway riders. The first-ever free daily newspaper in New York City started getting handed out to straphangers by determined hawkers back in 2003, an eventful year for the city’s iconic mass transit system.

Tokens and Blackout

2003 also saw the final discontinuation of tokens for payment, a full decade after the introduction of the MetroCard, and saw the retirement of the iconic Redbird trains, painted red to combat widespread graffiti in the 80s. And when the Northeast descended into darkness in August of that year, the subway lost its electric power, leaving hundreds of thousands of riders trapped underground for hours and the city in a state of paralysis.

Transit Strike

In 2005, trains came screeching to a halt for a different reason: subway personnel went on strike around Christmas, when the Transport Workers Union and the MTA could not agree on a new contract. The most recent New York transit strike, subway and bus service was all but halted for three days, causing not only a huge influx of traffic in Manhattan but also plenty of extra commutes by foot or bike. With the city immobilized, negotiations brought back transit service after progress was made on a pension dispute; TWU leader Roger Toussaint would, however, be sentenced to jail for leading the strike and the TWU was fined millions of dollars.

Global Financial Crisis

The global financial crisis of 2007-2010 forced state leaders to enact punishing cuts on the city’s transit system that would have major ripple effects later on. The move approved by the MTA in 2010 cut two subway lines, the V and W trains, and numerous bus routes, slashed frequency, hiked fares, and saw scores of employees laid off. Metro-North and the Long Island Rail Road also saw service reductions.

Superstorm Sandy

New York’s mass transit faced a cataclysmic test in 2012 when Hurricane Sandy hit the Big Apple: numerous subway tunnels flooded, some stations were destroyed, and service between boroughs was disrupted for weeks. The MTA estimated it incurred $5 billion in damages from the storm: in the years since, the agency has pursued costly and disruptive reconstruction efforts to fully repair the damage wrought by the storm and make the system resilient as the city faces a future of more frequent storms of a greater intensity than Sandy.

Hudson Yards & Second Ave Subway

on the 7 line opened in 2015, the first brand new subway station opened since the 80s. A little over a year later, the decades-long wait for the Second Avenue Subway finally culminated in the opening of three new stations on the Upper East Side serving the Q line. Each project cost billions of dollars.

Summer of Hell

Years of chronic disinvestment in the aging subway system came to a ferocious head in the summer of 2017, which soon came to be known as the “Summer of Hell.” Subway trains were running on time a pathetic 65% of the time, and people found themselves chronically late to where they needed to be. And after a string of derailments and an infamous incident where people were trapped in a scorching subway car, New Yorkers were quickly losing confidence in their city’s mass transit system.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who shouldered much of the blame for the crisis, declared a state of emergency and the MTA put together a rescue proposal called the “Subway Action Plan.” The MTA also hired Andy Byford to head the subways and buses and helm the rescue plan, and the cheerful Brit so delighted New Yorkers they took to calling him “Train Daddy.” Key among the necessary fixes identified was replacing the subway’s Great Depression-era signals with modern technology.

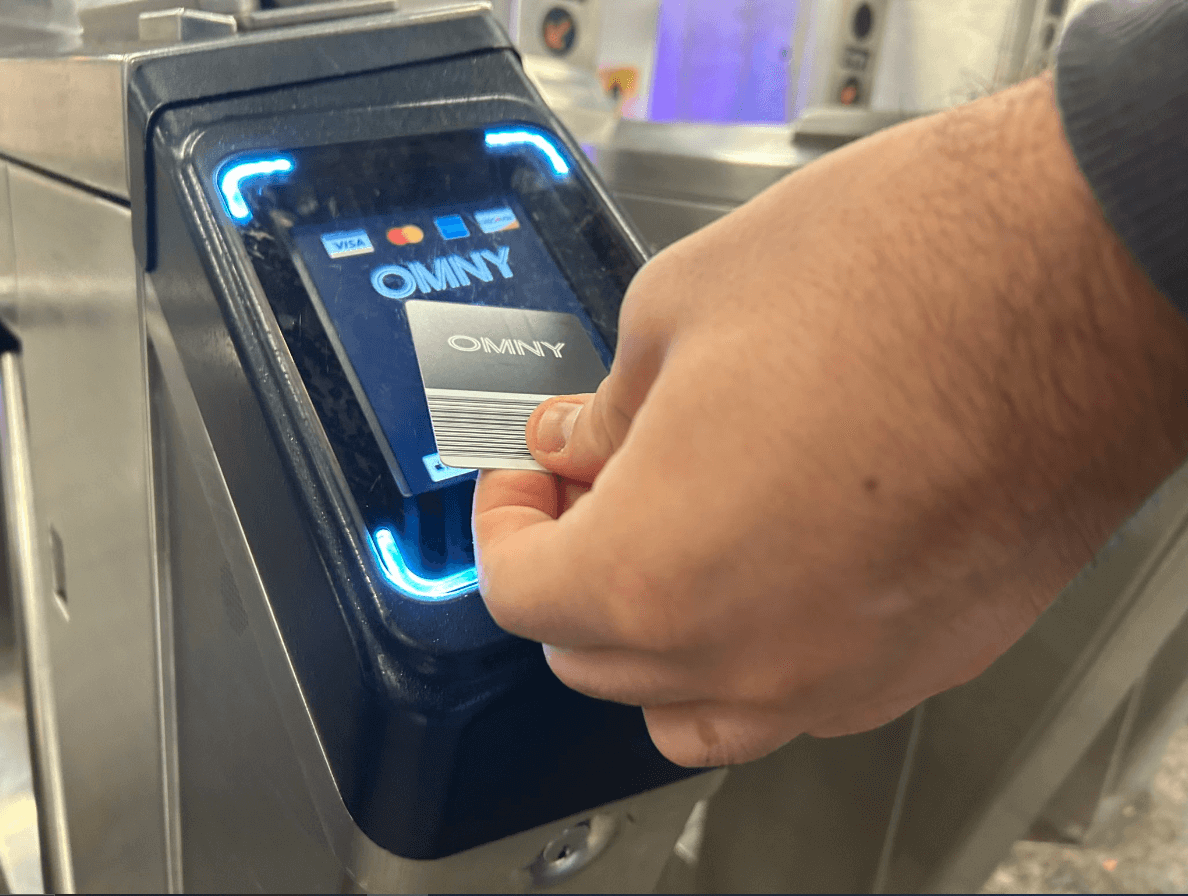

OMNY

After years of planning, the MTA introduced OMNY (short for “One Metro New York”), the tap-to-pay system slated to replace the MetroCard, in 2019. OMNY readers were installed on all subway turnstiles and buses by the end of 2020. Uptake on the new system has remained stubbornly low though, leading the agency to indefinitely delay the retirement of the MetroCard.

COVID

COVID-19 was perhaps the most devastating event in the history of New York mass transit. Ridership on subways and buses immediately plummeted as most New Yorkers were urged to stay home, decimating the MTA’s finances and necessitating what would ultimately be $16 billion in federal bailouts to keep the trains running. More than 100 transit workers lost their lives as they kept showing up while the virus ravaged the city, having been deemed “essential workers.”

When riders started returning, they were required to wear face masks for two years, which sometimes led to conflicts on the rails. The changes to commuting patterns caused by the pandemic have meant ridership has still not recovered fully, which led the state to pass a financial rescue package for the MTA which included tax and fare hikes.

New MTA?

Today’s transit leaders say they are running a “New MTA.” On-time performance for the subway has improved significantly since the doldrums of the Summer of Hell and is usually in the 80% range, though that’s still below the standards seen in comparable cities around the globe. Various lines are being re-signaled with modern Communications-Based Train Control (CBTC).

The MTA is eager to cast aside its reputation as the agency of can’t-do and inefficiency brought about by the Summer of Hell and various neverending projects: it completed its long-gestating East Side Access project last year with a brand new terminal under Grand Central, and plans to expand the Second Avenue Subway northward and reuse existing rails to make a new connection between Brooklyn and Queens, the Interborough Express, all while managing its aging infrastructure and addressing the threat of climate change. Funding for these priorities will depend on the success of its forthcoming congestion pricing program, which will toll motorists entering Manhattan starting on June 30.