BY KARI LINDBERG | A pair of chopsticks, a small table laden with bowls of sweet dumpling soup being eaten by an older Chinese woman, a wall painted the color of yellow pus with air bubbles and peeling flakes are all images reflected back in the photographs hanging on the second-floor mezzanine gallery of the new Pearl River Mart, at 385 Broadway.

The images are part of a multimedia exhibition titled, “Resilience / Resistance,” by the Chinatown Art Brigade, a collective of Asian American artists, media makers and activists with roots in New York City’s Chinatown, and will be running until Sun., Jan. 22.

Co-founded in 2015 by Tomie Arai, ManSee Kong and Betty Yu, the Chinatown Art Brigade seeks to use art to address broader issues of displacement and gentrification in Chinatown. According to the New York University Furman Center’s “State of New York City’s Housing and Neighborhoods in 2015” report, the Chinatown / Lower East Side area has seen a 50.3 percent percentage change in average rent from 1990 to 2010-2014, making it one of the city’s most gentrified neighborhoods during that period, second only to Williamsburg.

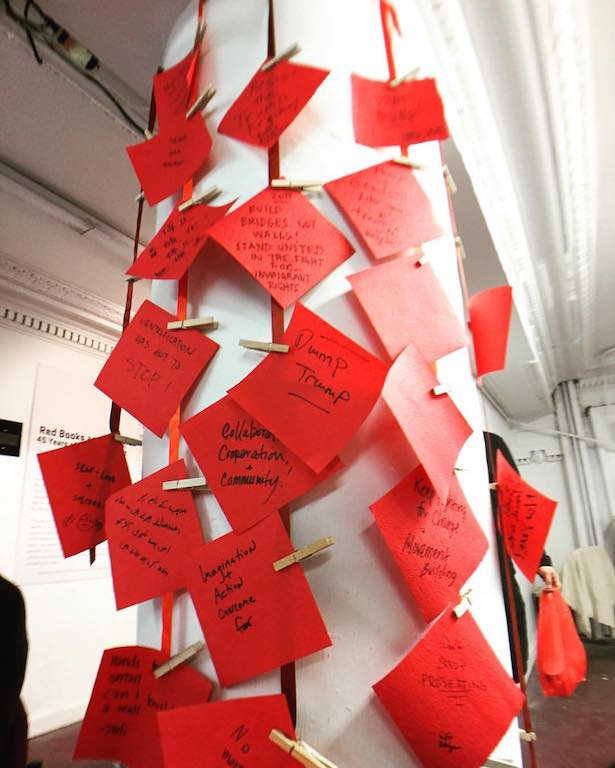

“Resilience / Resistance” provides a platform for the Chinatown Art Brigade to build a bridge between the Chinatown community and local residents unaware of its changes. In doing so, the exhibition has grounded its work on art produced by Chinese tenants experiencing landlord harassment.

“What makes our artwork unique, is that it is really centered around the tenants,” said co-founder Yu. “Not only are they resilient — like the title of the show — but also they’re doing their own organizing.”

Highlighting the tenant artwork is a series of six photos by three local Chinese tenant leaders who are organizing their buildings to fight against their housing conditions: Mimi Yan, who is still involved in a lawsuit with her landlord over living conditions; Zheng Zhi Qin, whose landlord cut off her building’s hot water as an eviction strategy; and David Tang, who was subjected to construction harassment by his landlord to make his building so unlivable that residents would rather move out.

Together their six photos show snippets of daily lives, ranging from a tradition of making sweet dumpling soup with friends and family, to buying produce from vendors underneath the Manhattan Bridge, to the physical walls of their home — yellowed with years of water damage.

Daily life is also given a voice though three continuously looping documentaries, made by co-founders Yu and See. One film by Yu documents her parents’ lives as Chinatown garment workers, while two others by See portray older Chinatown residents.

Adding to the emotional, visual and auditory mix are infographics made by Yu. These plainly state market-rate rents for the area as ranging from $1,200 to $9,500, compared to $934, which would be the rent for affordable housing for a family of four making the average median rent of $37,362.

Complementing these statistics on rising rents is the visual emptiness of living rooms in homes that no longer exist, as shown in Louis Chan’s photographs.

“These images, it’s the least I could do — photograph what existed when people were living there” Chan stated. “People who originally lived there moved out. Now those apartments have been renovated at market value and rented to people who are not immigrants and not Asian minorities.”

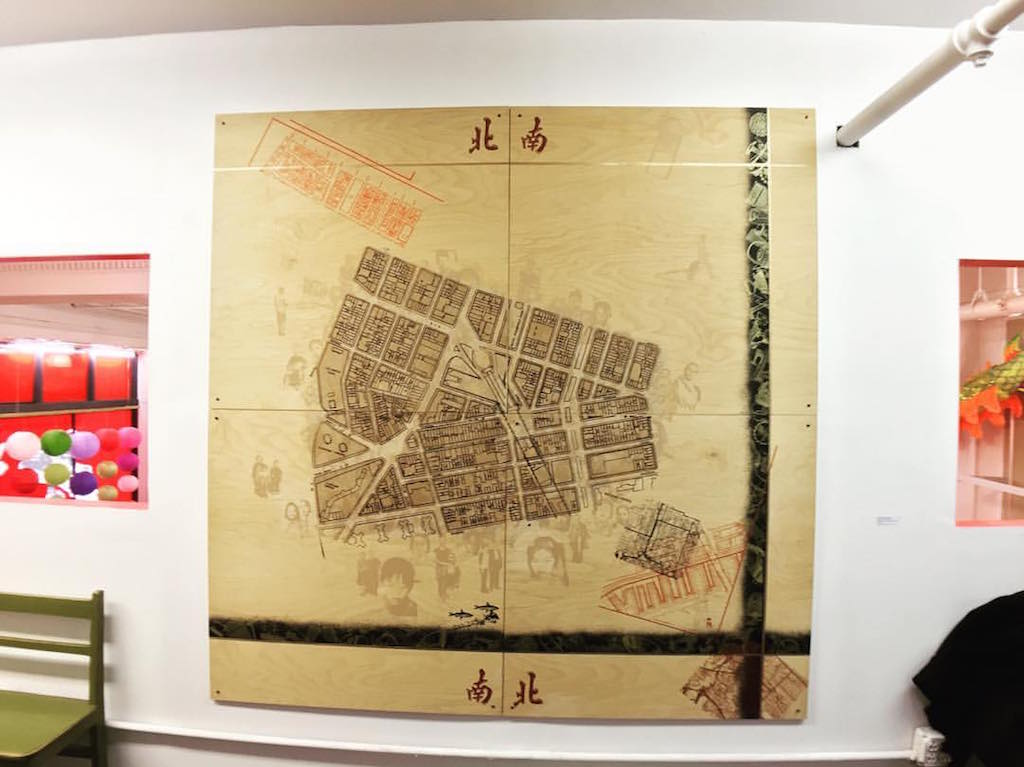

Additional facets of Chinatown’s changing landscape and identity are explored in a pair of photos by Enbion Micah An that show the two sides of the case involving Peter Liang, the Chinese-American police officer who fatally shot Akai Gurley in 2014. Exploring physical changes to the neighborhood, Tomie Arai created a large silk-screen map of the historic Manhattan Chinatown’s boundaries, an installation by Emily Chow Bluck of destroyed paper houses symbolizes the deterioration of tenant housing, and video by ManSee Kong also focuses on this theme.

Underlying the exhibit is the relationship between the Chinatown Art Bridge and Pearl River Mart, which is part of a larger strategy to involve all aspects of Chinatown life in the fight against gentrification.

“The idea is to work not only with residents and tenants,” Yu explained, “but also small businesses and landmark businesses in Chinatown that really have a stake in the gentrifying community.”

It’s a strategy that Pearl River Mart — New York City’s oldest emporium of mainland Chinese goods — supports.

“It is about being a participant in the community” said Joanne Kwong, president of Pearl River Mart.

Given the store’s beginnings in 1971, this should come as no surprise. Store co-founder Ming Yi Chen described its start as a “political statement and experiment” at a time when it was illegal to obtain goods from mainland China under the U.S. trade embargo against China.

Pearl River Mart’s continued 45-year success is still very much rooted in the community and culture of Chinatown. And, like the community it belongs to, the store has not escaped the financial realities of rising rents. Its current location at 385 Broadway, four blocks away from its previous Soho location, is closet-sized compared to its previous 30,000-foot-space.

Stumbling upon the store by accident, Veronica Chan confessed to taking Chinatown’s continued existence as a thriving community “for granted.” She found the exhibit a point of access to the changing realities of Chinatown.

“I just became more aware of what’s happening in Chinatown through the exhibit,” she said, “and I like that there are ways that it is turning into art, conversation and dialogue within the community.”