Earlier this year, many Chinese in the U.S. and China were shocked by a video posted on social media showing a Chinese immigrant who said he had been homeless in New York for 16 years after previously earning a considerable salary while working on Wall Street. In it, he speaks of his descent because of delusions.

The man’s identity and life story were soon confirmed by the media: Weidong Sun had graduated from a top college in China before earning his PhD degree in physics from the State University of New York. He had published 32 papers in science journals before his life was upended by a failed marriage and mental illness.

This May, as the celebratory atmosphere of the Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month began to be overshadowed by news of new rounds of layoffs in high tech companies, I found myself thinking about Sun’s troubles. The traditionally negligent attitude towards mental health within the Asian community fills me with dread, considering the potential number of Asians who have lost their jobs and may be experiencing a similar downward spiral.

The unemployment rate in the U.S. climbed to 3.9% in April, 0.5 percentage points higher than at the same time last year, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The jobless rate for Asians remains at 2.8%, the same as a year ago. However, 24.5% of Asians who lost their jobs have been unemployed for 27 or more weeks in the first quarter of this year, 5 percentage points higher than the average for the broader workforce and a 6.7 percentage point jump from a year ago. That is the biggest increase among all racial groups.

The high-tech industry, where Asian employees make up 20% of the workforce, has shed more than 80,000 jobs this year alone. The losses have come at many of the country’s biggest companies, like Tesla and Google. That was on top of the 263,180 tech layoffs in 2023, according to Layoffs.fyi.

The impact of a layoff on one’s mental health is undeniable and has been studied thoroughly. For example, a 2021 study by Irish and American researchers showed that Americans who were laid off at the beginning of the pandemic reported higher symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress than those who kept their jobs. Yet, when you look at the online forums catering to Asian professionals, where the subject of layoffs has recently become one of the most popular topics, mental health is rarely mentioned in the conversations. Even when someone reveals that he or she slipped into a serious depression after being laid off, most responders offer job searching tips and encouragement to try harder in their job search rather than suggest therapy.

This is no surprise. Asians are the racial group that is least likely to seek mental health services, according to Mental Health America, the leading organization promoting mental health awareness in the U.S. Studies have found various factors from language barriers to lack of health insurance as culprits. But to Weidong Sun and other highly educated Asian professionals, a tougher barrier that blocks their way to mental health services might be their unyielding pursuit of success cultivated by a culture that obsesses over academic and career achievements.

At “Fostering Asian American Mental Health,” a talk hosted by the Asia Society earlier this year, U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy, a son of an Indian immigrant family, shared his own struggles with mental health when he was younger. Once he thought about going to see a therapist, and then had cold feet because of the myth that it would affect his job opportunities. “I didn’t end up really following a path of actually getting help. So, I dealt very poorly with it,” Dr. Murthy said.

I have heard some of my friends and family members who were struggling after being laid off sharing similar concerns when I tried to persuade them to see a therapist. “The more educated the person is, the less likely they are to seek assistance when they have a mental illness,” Dr. Douglas Low, Unit Chief of the Adult Psychiatry Inpatient Service at NYC Health + Hospitals/ Bellevue in Manhattan, told me.

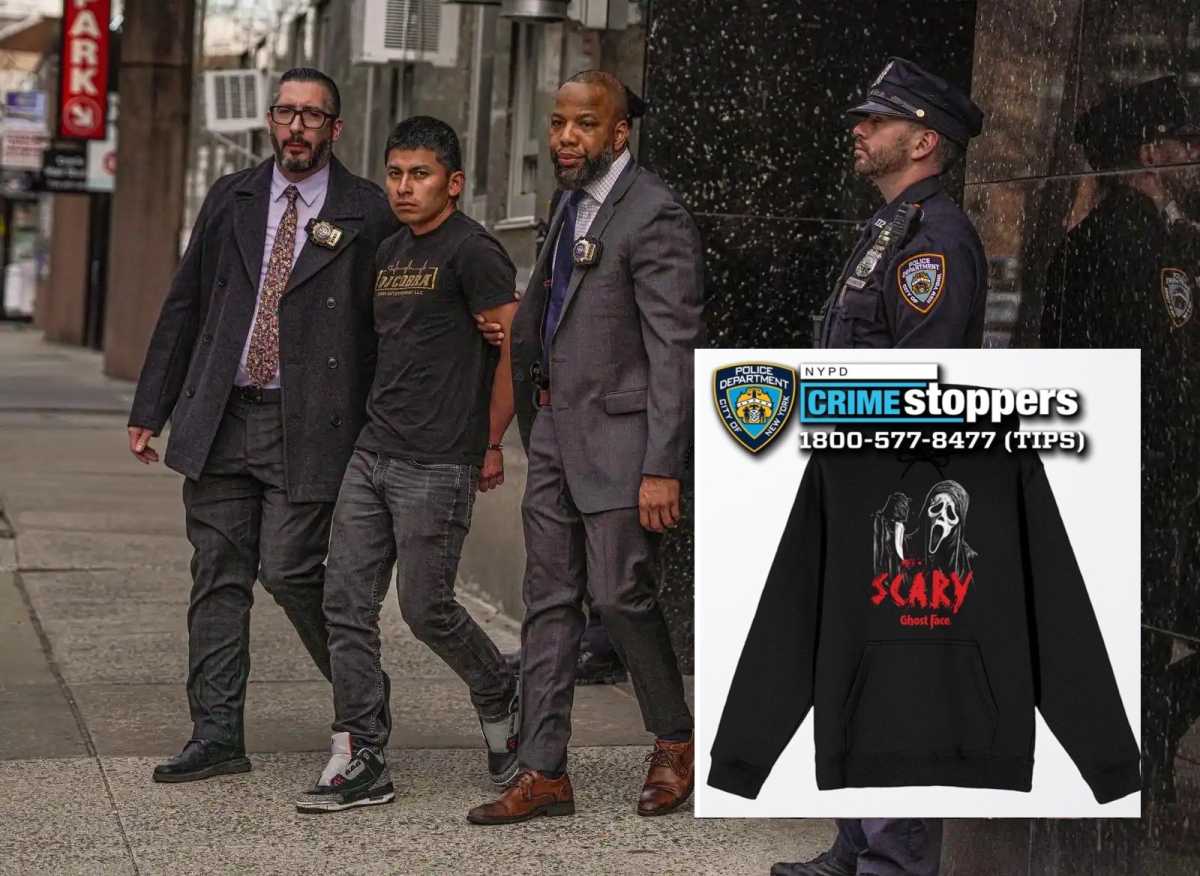

Sometimes, this neglect could lead to horrible consequences. Many in Silicon Valley still remember the 2008 fatal shooting at SiPort in Santa Clara, California, when Jing Hua Wu, a laid-off engineer killed three colleagues, including the CEO, in a fit of rage. Some will also recall the suicide of Qin Chen, a Facebook employee who jumped off an office building in 2018. Many employees would later share with media that they suspected it was the result of work pressures.

How can we make it easier for Asian professionals to seek mental health help? Through my job at MetroPlusHealth, I have gotten to know many mental health service providers who understand the Asian community and I turned to them for ideas.

Dr. Low, whose two children are in college and high school, said more community outreach is needed to normalize mental health challenges, and it should start as early as middle school or high school.

Steven Zhou, Deputy Director of Mental Health Services of the Department of Psychiatry/Social Work at NYC Health + Hospitals /Elmhurst in Queens, suggests all primary care doctors should screen their patients for mental illness symptoms routinely, even without being asked.

And Xiao Shi, senior Mental Health Supervisor of Behavioral Health Services at the Hamilton-Madison House, a social service organization in Chinatown, suggests employers integrate mental health awareness into the company culture by hosting mental health days or offering mental health awareness career coaching.

During Dr. Murthy’s conversation at the Asia Society, he also offered an idea. The Asian community often defines success with fame, fortune, power, and academic accomplishment, but these things won’t necessarily bring happiness. A different set of measurements based on a sense of belonging, purpose, and service can bring that sought after fulfillment, he said. “One of the things we have to do as a community is really come to terms with how we really define success,” said Dr. Murthy.

This may take some time for a community that is known for producing tiger moms. But it is never too late to start the journey.

Luna Liu is senior segment marketing manager of MetroPlusHealth, a New York City-based nonprofit health insurance company, providing access to high-quality, low-cost health care to the people of New York City.