The clock was ticking for BIBAK NY. After two months of intense preparation, the group was in its last 24 hours before they’d have to perform and compete in the 2024 New York Philippine Independence Day Parade.

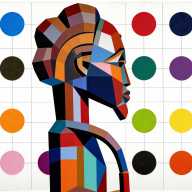

Out of the 135 performers attending the parade, only BIBAK NY represented the Indigenous Igorot and Cordilleran communities hailing from the six northern provinces of the Philippines: Abra, Apayao, Benguet, Ifugao, Kalinga, and Mountain Province. The performers had two and a half minutes to showcase their elaborate routines and dances in front of a panel of judges. Just 150 seconds to convey their heritage to a more global audience. Their participation in the parade will also pave the way for members to “meet new people in the Filipino Community as well to connect and interact with them, make friends and connections, and to inspire and be inspired,” said Leah Ticangan, a member of the group and a native Igorot from the Cordillera Region.

On a small hill in Cunningham Park, Queens, the feeling of excitement and pressure of the next day weaved itself into the group’s bustling final rehearsal last Saturday. The female dancers helped tighten each other’s bakget, or cream-colored ceremonial belts decorated with woven patterns of flowers. The group’s floral imagery and patterns trace back to a flower festival native to Northern Luzon. The men secured their Igorot headdress adorned with feathers wrapped in a red patterned fabric. Sprawled on a picnic table were straw hats with flower petals, neatly folded wanes, red-patterned loincloths to be worn by the men, and a long spear called baghay.

“They are custom-made and bought from the Philippines,” said one of the female dancers, pointing to the woven fabrics and the instruments. The group’s commitment to preserving indigenous heritage goes much deeper than cultural performing; it also involves utilizing paraphernalia originally made in the six northern provinces.

“We can showcase BIBAK NY’s heritage and culture through our ethnic dances and songs,” said Gerry Dupingay, a member from Ifugao province. “BIBAK NY is a great platform to express my Igorot cultural background.”

The BIBAK dancers synchronized their arms and footwork to the brass rhythm. A few minutes into the run-through, the group amassed a small crowd pulling out their phones to record or clapping along to the beats played by the male dancers, joining in the palpable enthusiasm displayed by the Indigenous dancers.

The day of the parade was no different. Trailing behind an extravagant float carrying pristine pageant queens, Mark Victoriano raises his gangsa, a brass handheld gong. He strikes it, leading two neat lines of dancers along Madison Avenue and 30th Street.

Finally, their dance begins.

With their arms raised, the line of women intersects with the men playing the gangsa, pacing themselves to the rhythm. Sounds rippling against the concrete buildings of Madison Avenue and the bold red and green fabrics swirling across the dull streets could not help but entrance onlookers.

The performance also showcased partner routines. One of the dances, sakuting, is a native war dance that pits two dancers against each other, as they wield wooden weapons called arnis and rhythmically strike each other. The other dance, the pinanyuan, is a native courtship dance where the two dancers use a piece of fabric to replicate catching one another.

While preserving their tradition, they also incorporate modernity into their routines and costumes to make them more accessible to younger generations. One dancer matches her attire with a baseball hat and shades; others add dances such as the boogie to their segments.

Roughly four hours after the parade, BIBAK NY found out that their months of practice had paid off: they were among the top three performances in the Independence Day Parade. Yet, BIBAK NY has no choreographer nor dance captain to credit. The intricate dance is traced solely to communal tradition and the “knowledge passed from generation to generation as early kids,” said Dupingay.

Despite dispersing into various states and countries, tradition is the thread that weaves indigenous individuals together. Their indigenous dances, Victoriana said, were learned through living and learning in their communities in the Northern Philippines. “It’s our culture.”