By Lincoln Anderson

A memorial service for Brad Will last Saturday filled St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery with a crowd of about 250 people.

It was then followed by a jubilant and rowdy procession through the East Village ending with marchers breaking into the former CHARAS/El Bohio for about 20 minutes, inside which they cavorted, scrawled graffiti, twirled a fire bolas and rode a bike.

An activist-turned-journalist, Will, 36, was fatally shot by government-backed paramilitaries in Oaxaca City, Mexico, on Oct. 27. He was documenting the occupation of the city by insurgents fighting for the overthrow of the state’s governor, Ulises Ruiz, when he was killed.

Outside the historic church on Second Ave. and 10th St. was a lavish spread of freegan food — from dumpster-diving or donations — tomatoes, cheese, whole wheat bread, juices. Will was a freegan who tried to subsist on food that would otherwise go to waste.

Calling Will “a prophet and a saint,” Father Frank Morales, the church’s associate pastor, said Will encompassed “fearlessness and determination, but also searing intuition about people.”

“His spirit will continue to inspire us, and his spirit ain’t going anywhere,” he said.

On a table near the front of the church were piled Will’s possessions: T-shirts, pants, a bunch of quarters, toiletries, “Cars Suck” stickers, a styrofoam head he must have found somewhere.

“If there’s anything Brad was, he was a scatterer of seeds,” said his friend Andy Stern, encouraging people to come up afterwards and take something from the table.

A photo montage of Will’s life was projected on the wall. The youngest of four children from a Chicago suburb, there were photos of him as a Cub Scout, then as a clean-shaven young man. As photos of the smiling mature Will with a beard and ponytail, as most remembered him, were shown, audible sniffles began to fill the church. A woman exhaled a loud sigh.

Brandon Jourdan, a colleague of Will’s at Indymedia, said Will — an avowed anarchist — was in the tradition of other American anarchists who fought and sometimes died for their beliefs, such as Sacco and Vanzetti and the striking workers at the Haymarket Riots.

Videos were then projected: Will riding a freight train; breathing fire at a Critical Mass after-party in New York City in 2003; Will just grinning in a Bolivian rain forest at night amid the cacophony of the birds and animals.

Kevin Svorak, a former roommate, said Will, like him, had “shed his privilege” in order to become a committed activist.

“Brad did it all with a lot of grace,” Svorak said. “That’s why he was so well loved. He understood what it was all about. But I don’t think he intellectualized it too much. It was about finding the next party and the next action.”

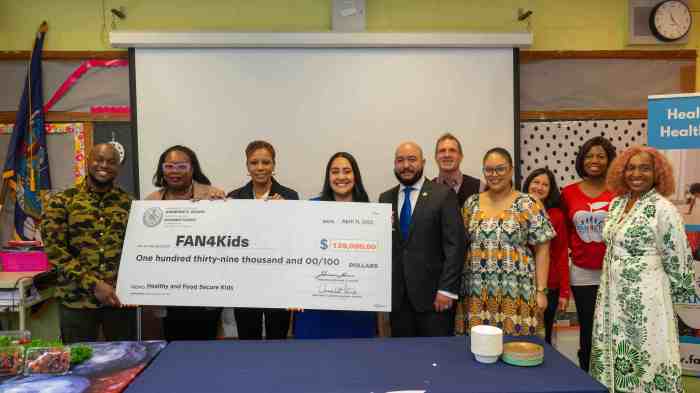

Sharing memories of Brad Will at La Plaza Cultural at the end of march through the East Village; next to the former Esperanza Garden, Torres family members and Brant Sharman,

More videos were shown, including one of the moment for which Will will probably be best remembered in the East Village, when he stood on the roof of the Fifth St. Squat in defiance of a wrecking ball that was knocking down the building. In the grainy, black-and-white video, Will throws his arms up in the air, in what looks like a cocky gesture, as if daring, “Bring it on!” Maybe, though, he was just trying to keep from getting killed by signaling to the demolition workers that he was there. The audience at the memorial applauded thunderously and pounded their feet on the floor at the sight of Will’s legendary face-off with the wrecking ball.

Another video showed Will in Esperanza Garden as his “black bear” lock was being sawed off by police. After he was arrested, Will speaking on camera, explains what he was fighting for: “New York can be so isolating — go home, watch TV and eat dinner. The Lower East Side is one of the last places where there was community.”

Harry Bubbins and other friends read passages from Will’s essay on the power of gardening from “We Are Everywhere.” From a section about the garden Will and others cultivated in a lot next to the Fifth St. Squat, Bubbins read, “Getting your hands into the soil is such a simple thing. You’re moving contrary to the concrete.”

In addition to being a gardener, Will was also a member of Earth First!, the radical environmental group. Priya, a.k.a. “Warcry,” recalled how when she first met Will he was tree-sitting in a harness 200 feet up in an old-growth Douglas fir in the Pacific Northwest to protect it from loggers. She noted that she’d just visited “Free” (Jeffrey Luers), an anarchist tree-sitter who is serving a 26-year sentence for torching three S.U.V.’s in Eugene, Ore., in 2000.

“Brad loved Free,” Warcry said.

Will’s two sisters, Wendy and Christy attended the memorial. Christy choked up as she read aloud Will’s last dispatch from Oaxaca, in which he described visiting a morgue to see the body of a man who had been killed the night before. The next day, Will’s body would be in that same morgue.

The Hungry March Band then led a raucous procession through the East Village past spots where Will had made a stand. As a black bicycle with wheels with spokes made of rebar in the shape of “A” for anarchy was carried amid the marchers, they walked east on 10th St., then down Avenue B. As they went, some wrote slogans on the asphalt with colored chalk: “Oaxaca Resist,” “Brad Will Presente” and what has become Will’s posthumous motto, “Stay in Trouble.”

Pausing for a moment by the Sixth and B Garden with its soaring trees and quirky tower structure, there was a moment of silence punctuated by the sounding of a conch horn. Next the procession wended its way to the site of the former Fifth St. Squat, now occupied by new housing.

Standing on a tree-pit guard, Michael Shenker, a fellow former squatter and roommate of Will’s, fired up the marchers by telling them, “The chant we used to say here was ‘Free the land!’”

Next they stopped on E. Seventh St. where Esperanza Garden once was. Today, it’s occupied by a building ironically named Eastville Gardens, where the Torres family, who live next door and had fought to save the garden, greeted them from their stoop.

“I always will remember Brad for the rest of my life,” said a Torres family member raising his fist in a power salute.

They then marched down Ninth St., stopping in front of the old P.S. 64, the former CHARAS/El Bohio arts center. The building has lain dormant for years as the community has struggled to keep it from being developed into a dorm and regain it as a community center. Someone had brought along a heavy-duty bolt cutter, and soon they had cut the chain on the door and about 50 people streamed through the construction fence and into the old building.

They graffitied on the walls — for Oaxaca, for Brad Will. A man on the old school’s front plaza twirled a bolas with fire on the ends. Someone zipped around through the hallways on a bike. Police in a squad car who had trailed the procession didn’t react. But after about 20 minutes, they all came out, next heading to La Plaza Cultural garden down the block. There around a burning barrel, stretched out in a large circle, people shared more memories of Will. Anne Bassen said she still has the black kitten Will gave her that he rescued from a squat being demolished; Fran Luck said Will was one of the few men who supported her feminist radio show. Andy Stern recalled how Will had rallied discouraged protesters at the International Monetary Fund meeting in Prague in 2000. Riding around on his bike, Will had gotten the Infernal Noise Brigade, a politically militant brass band, to start playing, which in turn sparked the “Blue Line” protesters back to life.

“Every corporate target in our path was totally destroyed,” Stern noted. He later said that while some anarchist protests involve property damage, they would never attack, for example, a mom-and-pop store. He said he and Will met in 1995 at Antioch College at a conference on anarchism. Asked if he felt Will had been targeted by the paramilitaries, Stern noted that Will had been actively pursuing them for the week up to his death. Asked if he thought Will had been perhaps too foolhardy, putting himself too near the gunfire, Stern said it was just bad luck.

“He didn’t want to die,” he said. “He loved his life.”

There were more memories shared about Will: about smoking joints while skinny-dipping in cold rivers, riding a freight train and then making love at the top of a grain silo in a thunderstorm. Many had come from all over the country to attend the memorial in the East Village.

Then someone started singing and playing guitar. Someone whipped out a flute and joined in. A guy with a drum came over and started beating out a rhythm. People started dancing around the fire barrel, dancing on into the night. From the raucous march through the East Village, to the heartfelt sharing of memories in the beautiful garden, to the breaking and entry into the former CHARAS, and the graffiti, all agreed, Brad Will would have definitely approved.