City Council members clashed with representatives of the real estate industry at a Wednesday hearing on a bill aimed at relieving renters from having to pay broker fees.

Multiple heated moments emerged during the hours-long June 12 hearing, in which council members traded barbs with real estate reps and chided Mayor Eric Adams’ administration for not sending certain officials to testify. The proceedings followed dueling morning rallies between supporters and opponents of the bill outside of City Hall — with the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY) claiming to have turned out 1,500 industry workers to its demonstration.

The legislation in question, known as the FARE (Fairness in Apartment Rentals) Act, would make the person who hires the real estate broker responsible for the fee; tenants are currently on the hook for the cost, most of the time.

Proponents of the measure argue that broker fees, which can cost up to 15% of a tenant’s annual rent, represent a significant financial burden to renting an apartment in the five boroughs. The bill comes as the city faces a massive shortage of available affordable rental housing, with just 1.4% of apartments in 2023 being available to rent — the lowest vacancy rate in five decades.

‘Plainly unfair’

Brooklyn Council Member Chi Ossé, the bill’s prime sponsor, said that New York is one of only two major American cities where tenants have to pay fees for brokers they did not personally hire.

“That system is bad for the economy, brutal for renters, and plainly unfair,” Ossé said, in his opening remarks. “The FARE Act will finally bring fairness to apartment rental expenses.”

Ossé said tenants pay an average of $10,000 to rent an apartment in the city, which he called a “burden very few people and families can bear.”

The council member re-introduced the bill after it failed to gain traction last year and has drummed up support for it through an aggressive social media campaign, involving videos with celebrities like “Broad City” star Ilana Glazer. So far, the legislation has garnered 33 co-sponsors.

On the other hand, the real estate industry charges the bill would not stop tenants from having to pay broker fees, because it would shift the cost of the fee into their monthly rent. Industry leaders also argue that the legislation eliminates the choice currently available to tenants to seek apartments with or without listed fees.

They claim 50% of the rental market features apartments advertised with no broker fee.

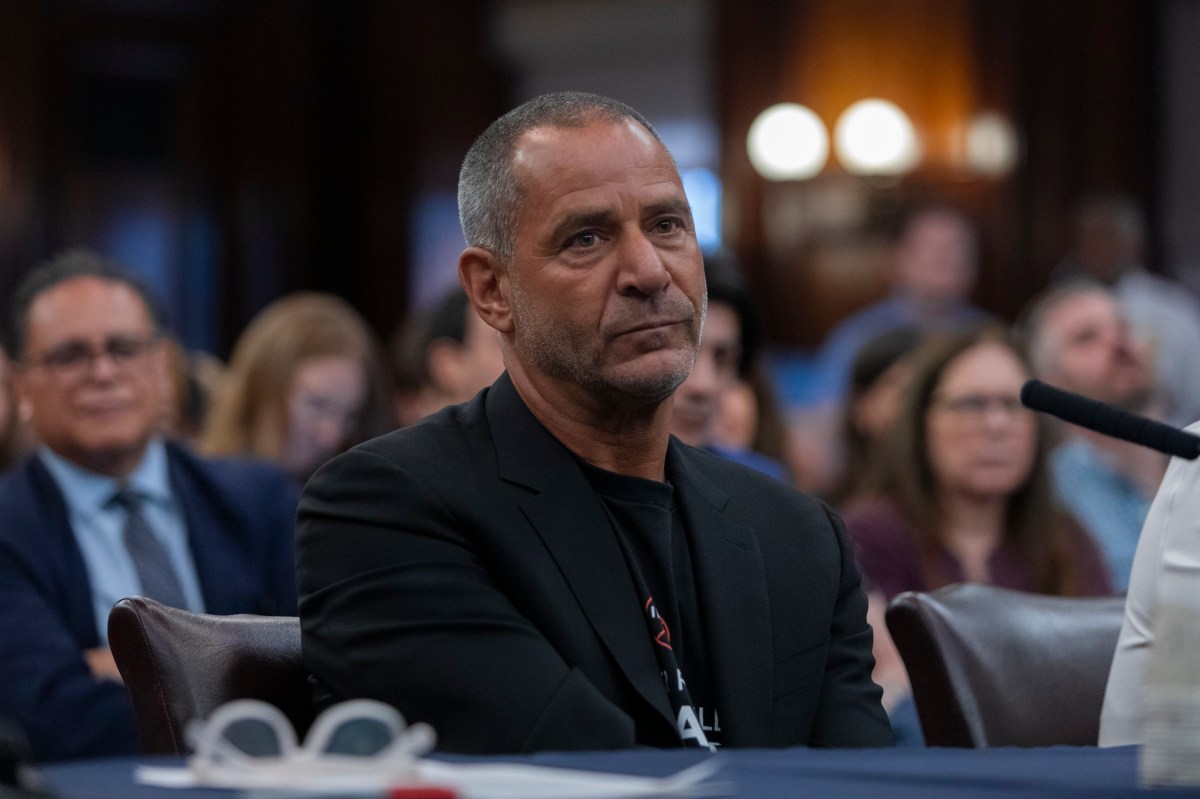

Gary Malin, chief operating officer for the real estate giant The Corcoran Group, argued in his testimony to the council that the bill would not lessen the high cost of rental housing across the city, but rather make it worse. He said the real issue the council should focus on is the lack of housing supply that stems from a significant slowdown in the amount of new apartment buildings being constructed in recent years.

“We all support a more affordable New York,” Malin said. “However, this bill will not achieve that goal. We face a supply and demand issue. Until we address this, pricing will not change. The market will become less negotiable. Landlords will become more rigid in the fees they charge, and these fees will be baked into the cost of rent, pushing them even higher.”

A no-show job?

One of the more fiery exchanges saw progressive Council Member Sandy Nurse (D-Brooklyn) try to push Malin on whether there is a requirement for real estate agents to physically show an apartment to renters.

Nurse, along with other council members in favor of the legislation, argued that most of the time brokers are not actually showing apartments to tenants. Rather, they claim, the brokers provide prospective tenants with the code to a lockbox to open the door themselves.

“The fact is, we have a situation where there’s people that we don’t meet who are supposed to be doing work, and we have to pay for their labor that we did not contract,” Nurse said.

Malin countered that his real estate firm always sends brokers to show apartments to tenants themselves. He contended that proponents of the legislation are overestimating how often brokers do not physically show up.

“That’s your experience in a limited situation,” he said. “I’m telling you what the law provides. You must sign a brokerage fee agreement clearly detailing what the costs are.”

Earlier in the hearing, council members became incensed when they learned officials with the city’s Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP) — the agency the council says would enforce the bill — did not show up.

They chided Ahmed Tigani, first deputy commissioner for the city Department of Housing Preservation and Development, for coming to the hearing without being able to answer their questions on data the city might have gathered related to broker fees.

“The amount of effort that goes in to getting us all here to this table, months of activity, to sit in front of a dais that is empty for such a critical issue is truly a slap in the face and seems to be the hallmark of this administration,” said Council Member Alexa Aviles (D-Brooklyn).

However, City Hall spokesperson Amaris Cockfield, in a statement, contended HPD showed up to the hearing instead of DCWP because the legislation amends the city’s housing and buildings code and not the DCWP section of its ad code.

“Ultimately, we firmly believe that the most important way to make housing more affordable is to build more housing,” she said. “We look forward to evaluating this legislation and listening to all public feedback on this legislation today, while diving deeper into the policy with the bill sponsors and stakeholders in the days to come.”