This story originally ran on our sister publication bxtimes.com.

On the first anniversary of one of the deadliest fires in NYC history, the Bronx Times revisited the Twin Parks North West tragedy through the eyes of some of its survivors, first responders and good Samaritans who witnessed the unthinkable events unfold that day. Much has changed since that fateful Sunday morning, but some things still feel eerily familiar.

-ET Rodriguez, Amira McKee, Nicholas Hernandez and Alyssa Cavero contributed to this article.

La Rubia Variedades, a small storefront that sits along a three-way intersection in Fordham Heights, is full of nearly everything Elizabeth Fermin’s customers need: Clothes, kitchenware, beauty products and children’s toys. But on a brisk December day, Fermin told the Bronx Times what she’s been missing at her shop for almost a year now.

“This little girl, she was 19 or 20, she used to come every weekend when she got out (of) her job and do layaways here and buy,” the store owner said.

Fermin was talking about Nyumaaisha “Aisha” Drammeh, who was just one of her customers who perished in the Twin Parks North West apartment fire last January. She said the young woman loved to shop for jeans and sneakers at her store, which is located directly across the street from the South Bronx high-rise on East 181st Street.

“Every weekend she used to come here, especially Saturdays,” Fermin said. “It’s very sad.”

Drammeh, whose mother and two siblings also died in the fire, was planning to begin college that February and had aspirations of becoming a lawyer, according to a report from THE CITY.

Tragedy strikes on a Sunday

For more than 50 years, the Twin Parks North West high-rise defined the Fordham Heights skyline. But now, on the first anniversary of New York City’s deadliest fire since 1990, the building is also the neighborhood’s tallest tombstone, standing 19 stories high.

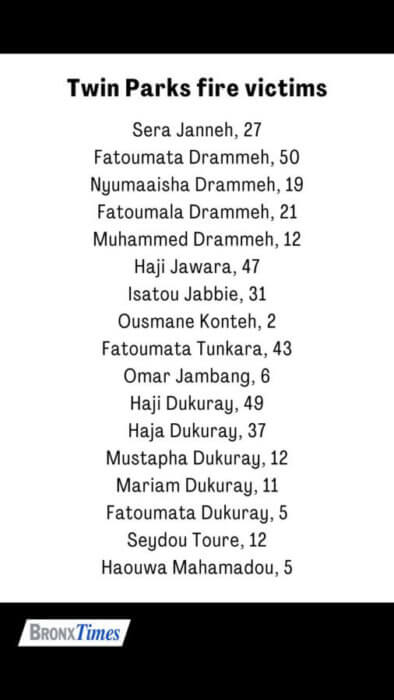

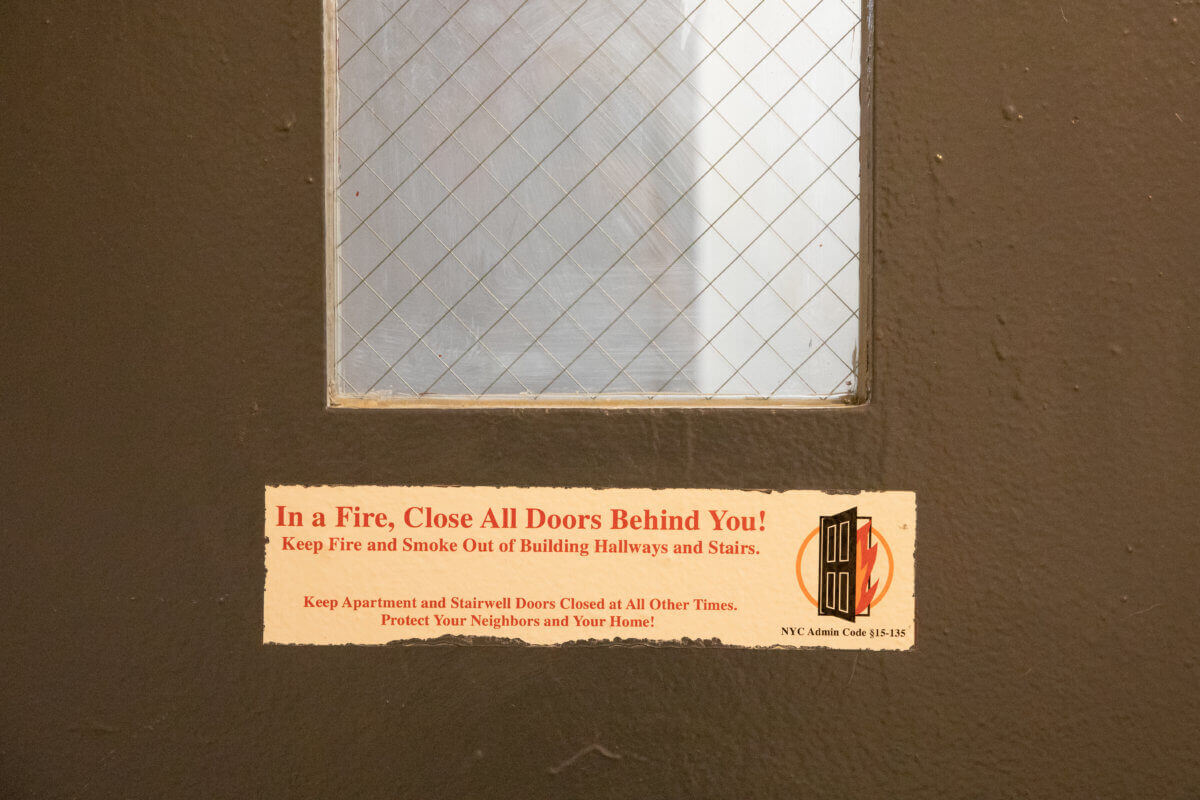

On the morning of Sunday, Jan. 9, 2022, shortly before 11 a.m., the FDNY responded to a five-alarm fire at 333 E. 181st St., the Twin Parks North West building. Deadly smoke from the blaze — which investigators found originated with a faulty space heater on the third floor that was left on for days — rapidly spread because of that unit’s defective self-closing door as well as a 15th-floor stairwell door that also stayed open. The fire claimed the lives of 17 people that day, including eight children. The youngest victim was just 2 years old, and all who died were of West African descent — 15 were Gambian and two were Malian.

For Fermin, it wasn’t just customers inside the building during the fire. Her aunt Virgen Peralta, a 15th-floor resident, had just finished cooking when she smelled smoke that January morning.

“I was doing the dishes,” Peralta told the Bronx Times in Spanish. “‘My stove was off, it wasn’t on, and I said, ‘What’s all the smoke that’s here?’”

She went to her room, no fire. Bathroom — nothing. But when the 63-year-old cracked her front door open, she said the hallway had turned into a dark corridor of smoke.

“I called and called and called my family,” Peralta said. “I called everyone to get me out because I was suffocating.”

Mahamed Keita, another tenant who spoke to the Bronx Times back in February, recalled running into a mother of two on the 12th floor the morning of the fire and carrying the woman’s 3-year-old daughter down the smoke-filled stairwell to safety. And from the street outside, Sandra Clayton — who testified in front of Congress in an effort to improve fire safety in federally-assisted housing in April — said she remembered watching first responders as they tried to resuscitate her neighbors, many of whom were already unresponsive due to severe smoke inhalation.

One of those first responders was David Cadogan, a Station 27 paramedic who recalled being overwhelmed by the magnitude of tenants emerging from the burning building that morning.

Cadogan told the Bronx Times in a December interview that he remembered looking up to the fourth-floor windows where the FDNY had extended a ladder to help tenants escape. And once the residents started coming out, it was a steady stream.

“The sheer scale of it was overwhelming. We train a lot, but you can’t train for something like this.”

— paramedic David Cadogan on the Twin Parks fire

“It was like literally going from drops of a faucet to an all-out waterfall,” he said. “There was just an avalanche of patients.”

On top of the 17 lives lost, 59 people were transported to various NYC and Westchester County hospitals. At the scene, 35 people experienced life-threatening injuries.

Cadogan, who has been a paramedic for 23 years, said it took him weeks to process the tragedy.

“The sheer scale of it was overwhelming,” he told the Bronx Times. “We train a lot, but you can’t train for something like this.”

Tenants, then and now

Some tenants, like Peralta, were comfortable returning to the Twin Parks complex even after escaping the flames. Others, like Hashim Valla, a Twin Parks tenant of four years, opted to take the city’s offer to relocate because of the post-traumatic stress he suffered from the events of Jan. 9, 2022.

“I went back to the apartment a few weeks after the fire, and it was too much for me,” Valla told the Bronx Times in an interview last month. “I heard sirens, I heard the cries of my neighbors, the smell of the smoke. … It still hasn’t left me a year later.”

At the time of the blaze, more than 300 people lived in the 120-unit building. All of them were displaced on that January morning, though they experienced different roads to recovery and stability.

Bronx Borough President Vanessa Gibson told the Bronx Times last week that the city’s response in the weeks and months after the fire was not without faults. But the blaze jolted a city — ushering in new administrations just days earlier — into crisis, one that soon overwhelmed officials.

“I know that people were unhappy, they were frustrated, they were pissed off, they were angry with us because this process wasn’t perfect,” said Gibson, who took office on Jan. 1, 2022. “There’s no manual on how to respond to a five-alarm fire where 17 people die. A lot of this we learned and led at the same time, and I acknowledge the mistakes and the mishaps that have happened … but I also acknowledge (the progress) made since Twin Parks.”

The night of the fire, the Red Cross provided emergency housing in several Bronx hotels to 22 families, consisting of 56 adults and 25 children, which rose to 34 families and 124 people the following night. Other residents found shelter through loved ones and community support.

Tenants who occupied floors 12 through 19 were allowed to return to their apartments two days after the fire.

But just a month later, displaced tenants began to share their stories through class-action lawsuits and public grievances over the city’s efforts to relocate them.

Some wanted to return to the only place they called home. Others who didn’t want to go back to the site of their trauma grappled with temporary homelessness, day-to-day anxieties over their next meal, and if they would ever feel at home again in the Bronx.

Following the fire, local volunteers urged New Yorkers to slow down material donations as they piled up, encouraging them to instead donate financially. The Gambian Youth Organization raised $1 million on GoFundMe in just four days; many members of the organization were also Twin Parks residents.

The city also stepped in, with the mayor’s office creating the Bronx Fire Relief Fund in the following days, which administration officials assured 100% of the proceeds would go to those affected or displaced. The effort brought thousands of grassroots donations and support from business and philanthropic community partners, which ultimately totaled $4.4 million in monetary and in-kind donations.

But in the two months following that announcement, there was widespread confusion from displaced tenants on how the money was being used.

And an array of hiccups for victims soon surfaced — such as cramped hotel accommodations and trouble expediting travel visas and death certificates for immigrant Muslim families hoping to mourn their loved ones in New York City.

When displaced tenant Yadhira Rodriguez spoke to the Bronx Times back in March, she said lodging accommodations in Bronx hotels were without microwaves and ovens, leaving many to fend for themselves.

As the city hit roadblocks with food provider contracts, local volunteers and donors tried to fill the gap through food deliveries until BronxWorks took over case management after March 17.

Affected families were given the option to relocate to La Central, an affordable housing development in the Melrose neighborhood 20 minutes north — or move back into Twin Parks with financial assistance in the form of moving and furniture credits, which was part of the city’s recovery effort in the much-maligned rollout of the mayor’s relief fund.

The mayor’s office confirmed with the Bronx Times that all the relief funds were distributed on behalf of Twins Parks tenants and families.

The ownership consortium of the Twin Parks building — Bronx Park Phase III Preservation LLC, which consists of Belveron Partners, the LIHC Investment Group and the Camber Property Group — confirmed that 79 households decided to leave their apartments after the tragedy.

“There’s things you can’t get back. Loved ones, that sense of home and sense of community, for me and others, died on that day.”

— Hashim Valla, a former Twin Parks resident

As late as September 2022, as many as four families were still struggling to find permanent housing.

Valla, the tenant who relocated after the fire, says he occasionally passes the building on his way to work in the Fordham Heights area. The wooden boards placed over broken, burn-stained third floor windows — which were only recently replaced with new windows — serve as a reminder, he said, that almost a year later, many are still recovering.

“There’s things you can’t get back. Loved ones, that sense of home and sense of community, for me and others, died on that day,” Valla said.

A building still in transition

From the upper floors of the 19-story Twin Parks North West, residents can peer out across the many rooftops of Fordham Heights until the buildings disappear into the horizon. But down below, reminders of the tragedy were still visible just four weeks ago, when the third floor where the fire started was gutted and still being reconstructed. Construction material occupied units, paired with temporary industrial lighting and exposed hallways.

But by last Friday, renovations to the third floor had neared completion. A spokesperson for the building said on Thursday that reconstruction is substantially complete, but that the property owners were awaiting agency signoffs.

A Bronx Park Phase III spokesperson said that as of Jan. 5, nearly one-third of the building was still vacant — including 14 units on the third floor.

In an email last month, Bronx Park Phase III confirmed the ownership group has spent more than $4 million in renovations to the building while also assisting residents, stating that there is “nothing more important than the safety” of their tenants.

A year ago, however, the 52-year-old building had already been flagged with 18 open violations and 174 total violations since the new ownership consortium had purchased the building in 2020, according to records filed with the city Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD).

Before the fatal blaze, some tenants claimed that smoke detectors in the building were so defective that they regularly experienced false alarms. Residents also had filed more than 30 complaints that detailed dangerous conditions in the year preceding the fire, including some that stated the apartments had no heat. Complaints that have since been closed.

The Bronx Park Phase III spokesperson said data from the building’s heat sensors on the day of the fire showed an average temperature of 71.2 degrees. The average temperature in the building in the 72 hours prior to the fire was 72.5 degrees, according to the spokesperson.

Still, some tenants decided to take legal action against building owners, resulting in lawsuits seeking billions in damages and distress – none of which led to any settlements by year’s end.

Calamity sparks fire safety

Even before Twins Parks, legislative improvements to federal, state and local fire safety had been long overdue. But the Jan. 9 fire brought a sense of urgency to prevent the next large-scale catastrophe.

As a direct result of the Twin Parks tragedy, the New York City Council saw legislative wins with Mayor Eric Adams signing five bills into law on June 1 that defines the term self-closing door in the housing maintenance code; reduces the time a landlord has to correct a self-closing door violation; prohibits the sale of electric space heaters without certain safety features; requires the FDNY to educate people about electric space heater safety and waives fees for permits to alter 1-3 family residences when the construction is addressing fire damage.

Adams also signed an executive order in March to increase coordination between fire officials and city HPD inspectors to identify fire safety violations earlier.

On the state level, Gov. Kathy Hochul signed into law the Safety Standards for Space Heaters on Dec. 8, which requires electric space heaters to have thermostats, automatic shut-offs and proper certification, a legislative response to Twin Parks.

The state Senate passed nine other fire safety bills in May and June that either didn’t make it to the Assembly or weren’t passed in the lower chamber — though most had been introduced prior to Twin Parks.

Nonetheless, 2022 drew to a close with what U.S. Rep. Ritchie Torres called the nation’s biggest progress in federal fire safety reform, as President Joe Biden signed Empowering the U.S. Fire Administration Act into law on Dec. 20, creating a process for the U.S. Fire Administration to investigate major blazes.

Torres introduced the act back in March, and also put forward three other fire safety bills last year that didn’t become law.

Improving federal fire safety — particularly for fire-prone, underinvested Black and brown communities — is an “ongoing effort,” Torres said.

The Bronx has been burning, some say, for at least four decades. Much of it, Torres told the Bronx Times, is due to underinvested and deteriorating housing stock that isn’t fully equipped with fire safety tools to combat or prevent structural fires.

The 1970s in the South Bronx was defined by landlord-driven insurance schemes to burn residential buildings in areas underserved by shuttered fire stations and neglected by the federal government. According to the documentary “Decade of Fire,” 80% of the South Bronx’s housing stock was lost to fires and 250,000 people were displaced.

The borough also saw arson fires in the 1976 Puerto Rican Social Club fire that killed 25 and the Happy Land Social Club blaze of 1990, which killed 87. But it was a 2017 fire in the Belmont section – which led to the deaths of 13 people – that resulted in legislation requiring the installation of self-closing doors by 2021.

“It’s unfortunate that it takes a tragedy to prompt preventative legislation,” said Torres, who represents the Bronx’s 15th Congressional District, which includes Fordham Heights. “The Bronx has had four of the deadliest fires in the city over the last 30 years and that’s not a coincidence.”

There had been a total of 17,617 reports of structural fires from 2018 to 2020 in the Bronx, according to 311 data. During those three years, the Bronx ranked second among the five boroughs for the highest number of structural fires, trailing only Brooklyn.

The Bronx neighborhoods of Throggs Neck, Co-op City, Morris Park, Morrisania, Crotona and Bronxdale all ranked in the top 10 citywide with the highest number of reports of structural fires, according to 311 data.

A report released on Monday by NYC Comptroller Brad Lander found between 2017 and 2021, portable heaters caused more than 100 fires in New York City residential buildings like the one that sparked the Twin Parks fire.

Amid a new year, Twin Parks evolves

Twin Parks was once the hope of late ’60s-era urban planners who thought adding a high-rise housing complex in Fordham Heights would prevent the white flight that soon metamorphosed a predominately Italian neighborhood into a haven for emigrants from Puerto Rico and the Gambia.

But Twin Parks North West has changed quite a bit since its groundbreaking 52 years ago.

For many, particularly those in the Gambian community, Twin Parks colloquially became the Touray Towers, when Abdoulie Touray became the first Gambian to move into the affordable housing complex in the 1970s.

Last year’s fire changed Twins Park even further, forever bonding its inhabitants and first responders in tragedy.

Although many surviving residents needed to leave after the trauma of Jan. 9, 2022, there were 41 households who confirmed they’d stay at Twin Parks, according to the Bronx Park Phase III spokesperson. And despite the building’s now devastating legacy, new tenants continue to move in.

Yeraci Gomez — who started living at the Twin Parks complex about 10 months after the fire — told the Bronx Times last month that he feels safe enough. The heat is set to a good temperature, he said in Spanish, and the building has a lot of new smoke detectors and security cameras.

On Monday, exactly one year since the fire, Twins Parks will be designated with a new street: 17 Abdoulie Touray Way, an honor to both the longtime Fordham Heights figure and the Gambian community that grew in the preceding decades.

Gibson, the borough president, hopes to add more to the neighborhood in the years to come, floating the possibility of a memorial similar to the one constructed after the Happy Land arson; a scholarship for the children of Twin Parks; or a community garden that ensures the stories of those affected are not forgotten.

“It’s been a year and we’re not talking about what happened,” she told the Bronx Times. “We’re talking about it now because of the anniversary, but after (Monday) we won’t talk about it anymore because we’ll move on with our lives.”

Four weeks ago, on a chilly December afternoon, a small section of Fordham Heights was relatively quiet. The sun, on its way down for the evening, cast a soft spotlight on the upper floors of the Twin Parks building as kids bundled in winter clothing made their way home from school on the sidewalks below.

Rosana Rosas and her 11-year-old son Nathan Berges examined the view out the window of their empty 12th-floor apartment that afternoon, before they were set to move into the Twin Parks building. Through the glass, they could see a golden sunset cascading over the distant Manhattan skyline.

Rosas said she was aware of the fire. She was in Fordham Heights that day.

“On that day I was near there … it was very, very scary,” Rosas said in Spanish.

But Twins Parks offers her something, she said, that is at a premium in the Bronx: affordable housing and stability.

“It’s more safe to live here than in my apartment (on the Grand Concourse) where I live now,” Rosas added.

Her son stood in the corner of the apartment, peering out the window. As far as Bronx apartments go, it’s hard to beat the skyline views that Twins Parks North West offers.

This story originally ran on our sister publication bxtimes.com.