Scientists now have a clearer picture of life for mankind’s earliest primate ancestors thanks in part to the work of New York City’s own Stephen Chester, paleontologist and assistant professor anthropology at Brooklyn College and The Graduate Center at CUNY.

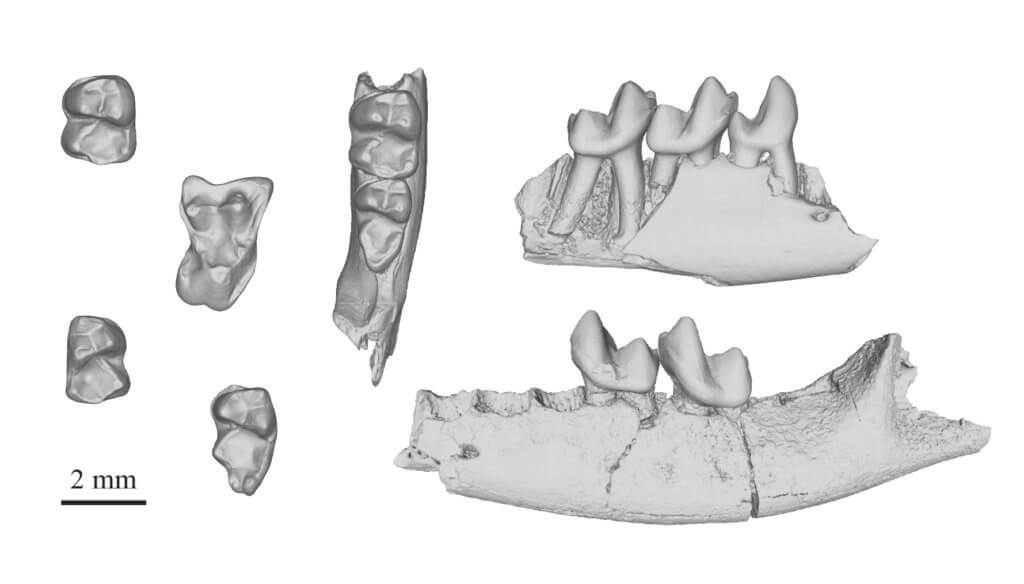

Chester, along with nine other researchers from across the country, recently helped analyze the first fossils of Purgatorius, the oldest genus in a group of the earliest-known primates called plesiadapiforms. These ancient mammals were small-bodied and ate specialized diets of insects and fruits that varied across species.

Chester and fellow researcher Gregory Wilson Mantilla, Burke Museum Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology and biology professor at the University of Washington biology, co-lead the study which analyzed fossilized teeth found in the Hell Creek area of northeastern Montana which are estimated to be 65.9 million years old, about 105,000 to 139,000 years after the asteroid that eventually killed off the dinosaurs hit the earth.

Based on the age of the fossils, researchers estimate that the ancestor of all primates, including plesiadapiforms, lemurs, monkeys, and apes, lived among large dinosaurs during the Late Cretaceous period.

“This discovery is exciting because it represents the oldest dated occurrence of archaic primates in the fossil record,” Chester said. “It adds to our understanding of how the earliest primates separated themselves from their competitors following the demise of the dinosaurs.”

Some of the Chester’s analysis took place in the Evolutionary Morphology Laboratory at Brooklyn College where he often teaches undergraduate students. But no students took part in the research for this latest project, the college says.

“Stephen Chester’s high-caliber impactful research in this area with Brooklyn College students has significantly contributed to our understanding of the environmental, biological, and social dependencies that ultimately led to the evolution of primates,” said Peter Tolias, dean of the School of Natural and Behavioral Sciences.

Chester, along with Mantilla, were also key members of a groundbreaking discovery of unusually well-preserved animals and plant fossils that revealed details on how the world recovered, and life evolved, after the asteroid impact.

After finding the fossils during a dig in Colorado Springs, Colorado, Chester and fellow researchers identified fossil mammal species, calculated their body mass based on measures of their skull and teeth and documented aspects of their anatomy to reconstruct their diet during the million years after the end of dinosaurs.

The team of researchers who collaborated alongside Chester and Wilson Mantilla in this latest discovery includes William Clemens from the University of California Museum of Paleontology: Jason Moore from the University of New Mexico: Courtney Sprain from the University of Florida and the University of California, Berkeley; Brody Hovatter from the University of Washington; William Mitchell from the Minnesota IT Services; Wade Mans from the University of New Mexico; Roland Mundil from the Berkeley Geochronology Center; and Paul Renne another scientist from the University of California, Berkeley.